10 Essential Artistic Reinvention Albums

Maybe it’s the arrival of spring, or perhaps it’s the new coat of paint on our website, but ideas of reinvention and renewal are fresh in our minds. One of the most ambitious and therefore difficult things for a band to do is to attempt a sort of artistic reinvention. To do so means to throw out everything you know, or at least acknowledge that you no longer want to follow that path. And if you have the ability to do that, then it likely also means you’re self aware enough to know what it is you’re turning away from. Suffice it to say, reinvention is a rare and curious thing, and sometimes ends up being a disaster (see: MC Hammer gone hardcore rap, anytime a metal band goes “electronic”). This week we highlight 10 of the best examples of artistic reinvention albums, from new personas to pioneering sounds, and all manner of identity shifting in between.

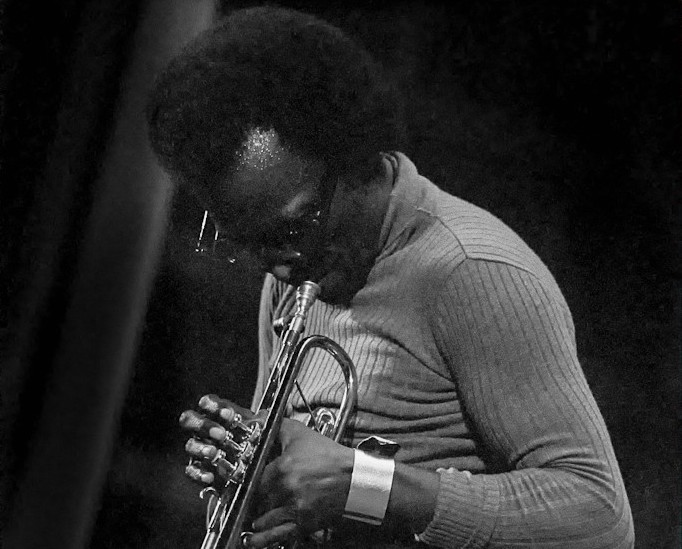

Miles Davis – In a Silent Way

Miles Davis – In a Silent Way

(1969; Columbia)

In Miles Davis’ 1990 autobiography, there’s an anecdote about being at a dinner hosted by Secretary of Labor George Schulz in which an unnamed politician’s wife got Davis’ ire up by asking, “What have you done in your life that’s so important. His response? “”Well, I changed music five or six times, so I guess that’s what I’ve done…Now, tell me what have you done of any importance other than being white, and that ain’t important to me, so tell me what your claim to fame is?” Indeed, Davis’ reputation stemmed almost as much from his tendency toward brutal honesty as it did artistic reinvention, but he was certainly telling the truth. Various points in his career could indicate some form of reinvention, though this is his gateway into one of the most radical periods of his career, beginning a series of “electric” albums that brought him out of a fertile hard bop period into a more rock-influenced fusion era. In a Silent Way is just two long tracks, each one taking up a full side of an LP, but each one is a masterpiece of composition (including some new experiments in tape editing), tone and texture. It’s a beautiful and atmospheric album, but it’s one of the most radical moments of Davis’ whole career. – JT

David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars

David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars

(1972; RCA)

Choosing just one album of David Bowie’s to represent his ability to reinvent himself kind of misses out on just how much evolved over the course of his career. In a sense, he was in a state of constant reinvention, adopting new sounds, personas and aesthetics throughout the years. Ziggy Stardust isn’t an arbitrary choice, however. After leaping from mod rock to psychedelic folk and kaleidoscopic pop, Bowie took on glam with this album, and in the process delivered what’s perhaps its greatest moment. A concept album about an alien rock star sent to save the earth (that’s the gist anyhow), The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars is as rich in narrative as it is in songwriting, and pretty much every song is a standout: “Suffragette City,” “Moonage Daydream,” the title track—I could go on. This wasn’t his first or his last great act of reinvention, but this was Bowie reintroducing himself in the most grand way possible. – JT

New Order – Power, Corruption and Lies

New Order – Power, Corruption and Lies

(1983; Factory/Qwest)

In 1980, Joy Division came to a tragic and abrupt end when singer Ian Curtis committed suicide. Rather than continue on with the same name, however, the remaining members of Joy Division hit the restart button by launching a new band: New Order. It took a year or two before they were able to truly separate themselves from their previous work, however, as debut album Movement felt mostly like a continuation of Joy Division’s dark, mournful post-punk, albeit with some novel electronic elements. That all changed with 1983’s Power, Corruption and Lies, an album that took New Order out of the shadow of Joy Division and positioned them as synth-pop heroes. In the U.S. market, the album was released with megahit “Blue Monday,” the 12-inch single of which sold more than a million copies. But the album itself is a much more physical and sleek transition away from the abrasive punk textures of previous years into something equally abstract and dark, but more accessible—even fun! In just three years, New Order went from picking up the pieces of a broken band into delivering their quintessential album. – JT

Tom Waits – Swordfishtrombones

Tom Waits – Swordfishtrombones

(1983; Island)

Tom Waits’ tempered beatnik persona of the ‘70s produced a barrel of great songs, but by the time he hit his thirties he may have been feeling around the edges of a cul-de-sac. Hints of artistic impatience had been dropped on works such as “Potter’s Field” and “Red Shoes By the Drugstore,” not to mention the luridly uncomfortable cover of his Heartattack and Vine album. Newly married and rethinking the point of full string sections, Waits simply blew everything up on Swordfishtrombones and saved some shrapnel for percussion. It’s a Fellini movie on wax, trading in slick orchestrations for rusted drums, tipsy marching bands, mangled guitar by Marc Ribot and a limping sense of dread. Waits’ characters were likewise liberated from the dive bar to court death or affliction more personally, whether from war (“Shore Leave,” the title track) or a blind dog with skin disease (“Frank’s Wild Years”). The deconstructed music allowed Waits to make more impressionistic lyrics that created compelling scenes of displacement in “16 Shells From a Thirty-Ought Six” and “Down Down Down.” Swordfishtrombones was the most insane, high-risk move a California rock musician had ever tried, but a very high-reward one as Waits developed a bigger, more devoted popular following in its wake. – PP

Johnny Cash – American Recordings

Johnny Cash – American Recordings

(1994; American Recordings)

When you think of producer and label executive Rick Rubin you think of musical beginnings. He evangelized for Beastie Boys at the start of their career and launched Red Hot Chili Peppers into the stratosphere, but we might be most thankful that he set Johnny Cash on the last productive path of his life. Cash had long griped about his albums feeling overproduced, and signed to Rubin’s nascent American Recordings imprint after miserable periods with Columbia and Mercury. Their first work together found Johnny with just a guitar in living rooms and on club stages, comfortably owning everything from lost chestnuts (Jimmy Driftwood’s “Tennessee Stud,” Leonard Cohen’s “Bird on a Wire,” the cowboy ballad “Oh, Bury Me Not”) to then-new writing by Nick Lowe, Tom Waits and Glenn Danzig (all of whom would later record those songs themselves). It was the humble beginning of what would become a massive effort—six releases across two decades—to affix Cash’s powerful sonic legacy as The Man in Black to a brand new generation of listeners. – AB [This is based on a review that originally appeared here.]

Scott Walker – Tilt

Scott Walker – Tilt

(1995; Fontana)

The career of the former ‘60s it-boy in Britain was already known for its unpredictability. American Scott Walker was a teen idol with the Walker Brothers who abruptly altered his course towards the more serious lyricism of Jacques Brel in his solo efforts. Shedding fans in increments with each chapter in the ‘70s and sloughing through a well-received reunion with the Brothers, Walker toyed with experimental melody and instrumentation with his 1984 album Climate of Hunter, then vanished for 11 years. Then came Tilt, practically released under cover of obscurity. Never mind being conventionally enjoyed, Tilt frequently dares to even be described. Walker composed his works in units of “sound blocks,” chunks of saw-toothed noise, indefinite melodies, operatic and cabalistic lyrics and apprehensive atmosphere. Kind listeners called it a challenge; hornswaggled listeners called it an assault. “The Cockfighter” subsists on a grotesque, churn-like device for rhythm; “Manhattan” mocks youthful urban optimism with a dreading prelude and the confirmations of our worst fears. “The Patriot (A Single)” is nationalist adult contemporary on absinthe, deconstructing every horrid cliché it sends up with stark, malformed horror. Walker didn’t just untether himself from his past: Tilt was a detachment from all notions of Western popular music. His subsequent album The Drift (after another 11-year break) was even more discordant and blood-drenched, rendering Tilt a little more approachable by comparison. But it started Walker’s long, twisted, happily disrepaired road toward absolute consumption by his art, and one of the most fascinating late-period pop careers that will ever be. – PP

Blur – Blur

Blur – Blur

(1997; Food/Virgin)

After the long, bloody, largely fabricated Oasis-vs-Blur War was won by the former via death by “Wonderwall,” Damon Albarn and the rest of Blur shuffled off to re-regroup from seven years of smart Britpop and tabloid burns. Their self-titled album was released in 1997 without a lot of customary build-up—probably because their British business partners feared the dramatic change in sound might divide their fans. Instead Blur was the first step in Albarn’s gradual reinvention as one of the more nimble, forward-looking artists of his generation and became their biggest American album. Albarn drew influence from guitarist Graham Coxon’s deep appreciation for sub-mainstream artists, particularly Pavement, and scuffed up their sound with more instrument separation (“M.O.R.”), distorted guitars (“Death of a Party”) and carefully executed synthesizer damage (“On Your Own”). The two big warning shots, “Beetlebum” and “Song 2,” came right up front and announced their change in direction without reservation. They became their most emblematic hits—especially “Song 2”—and set up an album that moved them in more capricious directions without sacrificing Albarn’s overt Britishness or rooted gift in melody. On a broader scale, Blur set Albarn up on a path of rejuvenated and committed adventure: his African-infused solo album Mali Music, the patched-together supergroup The Good, The Bad & the Queen, Blur’s excellent deep dive releases Think Tank and The Magic Whip, and of course the greatest virtual band in music history, Gorillaz. And even Noel Gallagher is joining him onstage now—you know how war veterans bond. – PP

Bob Dylan – Time Out of Mind

Bob Dylan – Time Out of Mind

(1997; Columbia)

With a catalogue as varied as Bob Dylan’s, how do you choose one album to represent a reinvention? One could argue that the electric Bringing It All Back Home marked Dylan’s big turning point. One could say that Blood on the Tracks ushered in an era of a kinder, sweeter Dylan. However, the frequency and variety of new, original material from the ‘60s through the ‘80s was such that fans and critics couldn’t keep up with his changes. In the early-to-mid ‘90s, Dylan had finally faded from relevance. I saw him play to 700 people in Philadelphia in 1995, and cringed as he incomprehensibly gargled lyrics, rendering the tunes almost indecipherable. Then in 1997, the thick, rich, dark Time Out of Mind was released. His voice was still gravelly, but pure and strong, and it suited this troubadour, here in his mid-50s. The next time I saw him, in 1999, ranks as one of the top three concerts I’ve ever seen. He performed old songs in this new style, engaged the band and the audience, and sounded healthy and wise. Subsequent albums share a thread with Time Out of Mind. Even though each has its own personality, there’s depth and precision in the songwriting and performances that might not have been explored if not for this mid-’90s masterpiece. – CG

The Flaming Lips – Zaireeka

The Flaming Lips – Zaireeka

(1997; Warner Bros.)

No one could have predicted the Napoleonic ambition The Lips would be known for upon the release of their eighth album. However, following the departure of extraordinaire guitarist Ronald Jones, the band practically rebranded themselves overnight. Their next album came with an absurd premise: four CDs meant to be played on four CD players simultaneously. And yet, the most bizarre plot twist in the story is the mind-shattering sonic experience that ended up overshadowing the gimmick entirely. Casting off all remaining vestiges of standard rock and roll that were left, The Lips blasted off into cosmic territory. “Riding to Work in the Year 2050 (You’re Invisible Now)” and “A Machine in India” are a couple showstoppers, featuring warped synthetic strings, groovy bass-lines and “bleeding vaginas.” The Soft Bulletin came two years later and was deemed their startling breakthrough, but this breathtaking symphonic platter proves that the rebirth had already arrived. – RR

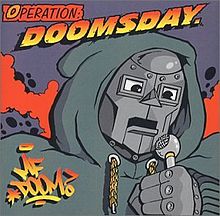

MF Doom – Operation: Doomsday

MF Doom – Operation: Doomsday

(1999; Fondle ’em)

Daniel Dumile began his career in hip-hop with KMD, rapping under the name Zev Love X. When his brother and fellow KMD member Subroc died in 1993, however, KMD folded and their second album Black Bastards was shelved due to controversial cover art. Dumile retreated for most the remaining years in the ’90s, grieving and depressed. As the decade drew to a close, however, Dumile adopted a supervillain identity as a clever gimmick in an effort to seek revenge on the industry that wronged him. Villainy proved to be a creative boon for Dumile, his debut album as MF DOOM full of abstract verses, comic book references, stoner humor and some of the best beats of his career. Sure, he presented himself as an adversary, but in the process he became a hip-hop hero.