Come: Prince’s most deranged plot twist

We often take the enshrined legacy of Prince for granted. As the ’90s seeped in and the Purple Rain days continued to recede, his stature was somewhat compromised and in question. His fifteenth album was released in 1994, long past his most colorful decade in the ’80s and deep in the mess of a record label war. As his sights were then set on releasing new music in formats totally outside of the album as his new unpronounceable moniker, this record was his contract fulfiller with Warner Bros., an attempt to finish business and clear the vaults a bit. Listening to the music, it’s totally mystifying that what he gave the men in suits above him wasn’t a simple boring cash-in but something totally bizarre instead.

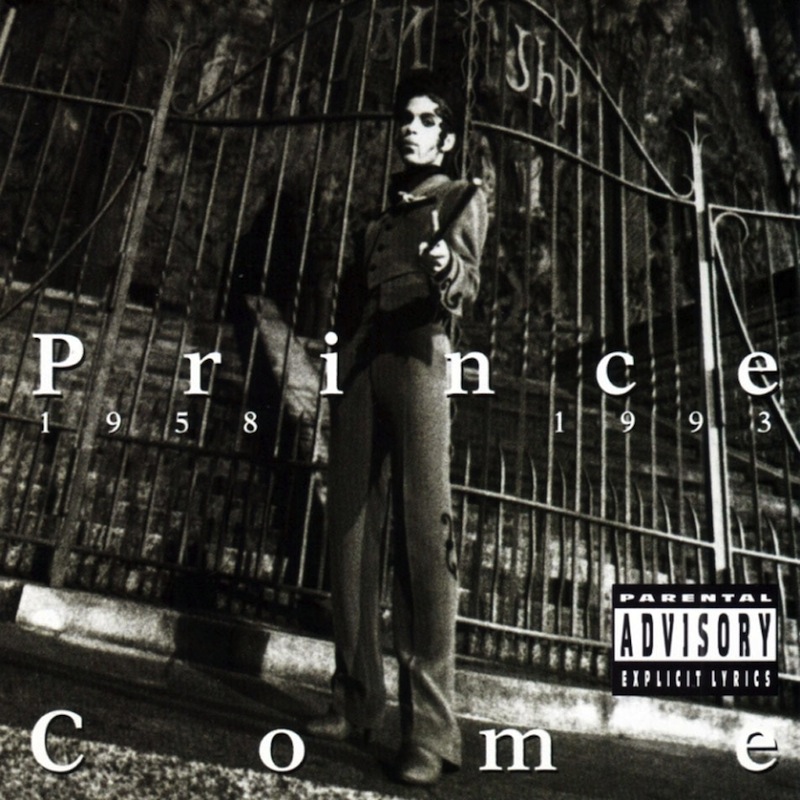

Come is searching and introspective and is, therefore, confusing and contradictory too. The album’s cover features The Purple One arms crossed in the distance, with an imposing gothic church behind him in the nightly backdrop. He feels untouchable and faintly out of touch, frankly, a bit off. Come would also see our idol’s first death: the years 1958-1993 appear. ’58 is the year Prince was born, implying on the cover his own demise (around the same time, he adopted the Symbol as his new stage name). The ghostly entity pictured therein lives in a world far-removed from the days when the Pop scene was truly Prince-centric, when other artists constantly looked up at him when trying to stay fresh and digable. By this time, he was free to dig deep into his own recesses, re-hash and indulge without care for Pop’s trajectory. It makes sense that Come it didn’t make much of a dent in pockets. At the same time, it’s criminal that so few ears were and are still exposed to this side of the artist. What so many missed out on was a much bleaker take on Prince’s usual uplifting every-(wo)man image, and a revealing outpouring of emotions usually kept locked up inside.

Many of the songs were actually written for an abandoned musical loosely based on Homer’s The Odyssey, which is a loner’s saga if there ever was one. The music reflects what at least seemed on the surface to be Prince’s then-new tug of war: still craving a Superstar’s relevance versus wanting to be left alone. “Solo” is a sung poem carried entirely by Prince’s voice with the exception of a harp that occasionally glides in and out. Both the title and music imply that he’s on his own, and yet he relied completely on words written by someone else (namely, Chinese-American playwright David Henry Hwang). “Pheromone” closely details Prince’s lusting over Electra, the beautiful daughter of King Agamemnon who seduced Odysseus’s men with potions. It’s a dark fantasy that sees him getting off to watching his lover engage in sadomasochistic sex with another man from afar—alone yet in agreement with another. And to return to The Odyssey, did Odysseus, so alone, not rely on many others to survive? Wasn’t that also in many ways the point? “Letitgo” is the last actual song on the album, and in it Prince resignedly but decidedly admits he’d rather open himself up to others than hole himself up in seclusion, something he was perhaps very familiar with as a recording perfectionist with music always in his head. Throughout Come, there’s the constant danger of psychological self-torment and isolation going too far.

Mixed messages continue to reveal themselves the further you delve into Come’s twisted narrative. “Loose!” funnily mocks the aspiring machos of the world with lines like “Bangin’ gangs, slangin’ wangs and rock” and is echoed in aesthetic later by artists like The Knife. In those ways, it sounds futuristic and progressive. On the other hand, he points a finger at (and tries to distance himself from) hip-hop in another line: “I got the clothes, I got the bank and the crew,” appearing to diss the whole genre as empty posturing, which he was inclined to do around this time even as he flirted with the genre himself. Still, he does end up rapping on another song on the same record, “Race.” As ever, the points get pretty convoluted, and deeply reflective insights about how racism affects black people in one breath are shared by “we’re all one” sentiments and reverse-racist pleas for others to either shape up or save themselves the trauma by remaining ignorant. It’s a deeply sorrowful case that really feels personal and affecting in spite of and because of his deeply conflicted feelings.

Comparing one vaguely “dark” album to another is an often superficial exercise for critics. In this case, there are just too many parallels between this album and particular works from mega pop stars that came after it not to state the obvious. Both visually and in sound, the grime of Come eerily brings to mind Eminem’s famed 2000 release The Marshall Mathers LP, another naked outpouring of emotions that walked unsteadily the line between comedic shock and real vulnerability. An example that came to mind a bit later was Kanye West’s Yeezus, which was both another masterpiece and his documented fall from grace. Just as that album mixes and melds social commentary, graphic sex, and the haunted self-examinations of a pop star who’s clearly detached, so too does Come. The two are also similarly noteworthy for their willingness to blend the old Soul with brand new genre explorations, the latter being choices made to give the artists’ a sharper edge and helping accentuate the atmosphere of death.

The last instance that seemed to echo Come’s procession obsession was from this very year and was cloaked in its own tragic aura: David Bowie’s Blackstar, and his staged death. Though obviously not as grimly real as The Thin White Duke’s performance, Prince’s move with his fifteenth album was a similar announcement of a beloved artist dying and something else taking over—even in real terms, both records begin with 10-minute-long title-tracks, though that’s beside the point. Both albums saw their creators move into stranger territory than they were used to, adopting more transitory, “floating” personas and offering eerier soundscapes from which to communicate to us.

Speaking of “Come,” the song that shares its name with such an anomaly of a record, this is truly where Prince most beautifully imagined the flow of sex and death, breaking free from all expectations and delivering something new, pulsing and transcendent. In the song, a woman’s voice repeats “Come,” which lasts for nearly every measure of the tune’s long stretch. Meanwhile, Prince tries every Prince vocal in the book while the TLC-invoking drumbeat carries on. Soon enough, horns blare in longing, diverting the song from its slow, seductive course until every instrument soars, including his voice. His unearthly falsetto makes increasing leaps, literally at its peak crying “oh yes! oh yes!” The sensuality doesn’t feel superficial at all, but heavenly, which is what Prince always did best. In a year of tremendous loss, it feels more urgent now than ever to hear the legend that passed away act as his own eulogist. Then again, The Purple One was no ordinary preacher.