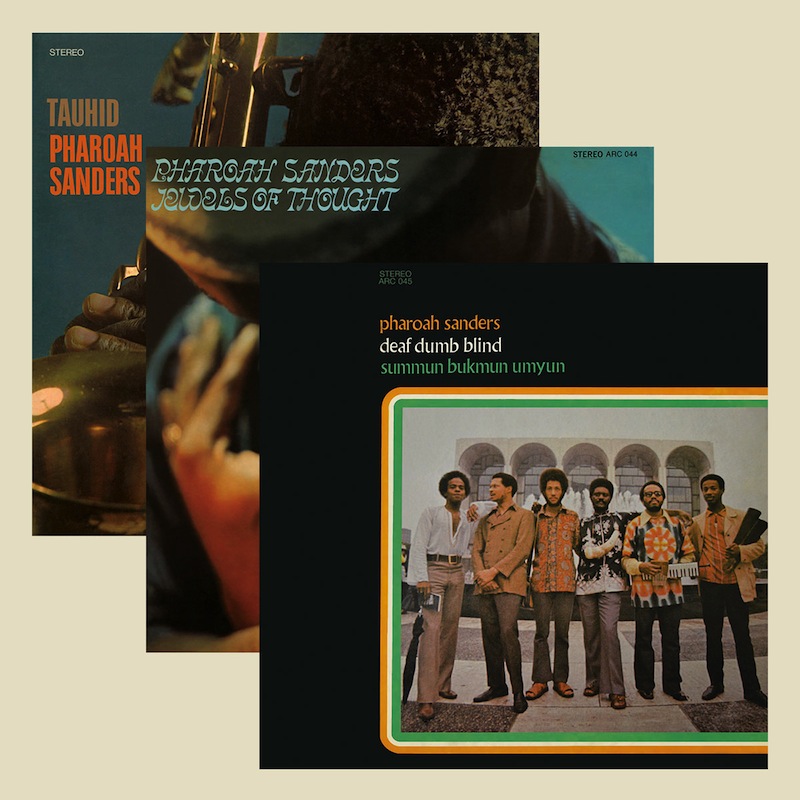

Pharoah Sanders : Tauhid/Jewels of Thought/Deaf Dumb Blind

The story of spiritual jazz neither begins nor ends with Pharoah Sanders, but his presence comprises its most significant chapters. His musical expression evaded easy marketing or easy comprehension, a profound and deep work of transcendent feeling that, while frequently featuring Sanders’ own voice, was beyond words. In fact, label suits in the mid-’60s didn’t quite get it; legendary jazz producer Bob Thiele, upon delivering Sanders’ Impulse! debut Tauhid, was met with sneers of “What kind of crap is this?” The face of jazz was changing, whether they were ready to accept it or not. And Sanders was the one changing it.

Sanders’ early career came to life in the shadows of another giant. His first album, Pharoah, was released in 1964 after some time spent performing with Sun Ra, who gave him a place to stay, some new clothes and dubbed him “Pharoah.” But it wasn’t until Sanders joined up with John Coltrane for the moving, chaotic and form-destroying Ascension that he began to come into his own and find his voice, both literally and through the intense, furious playing of his saxophone. Much like Coltrane, Sanders was a born and raised in the South but launched his career in New York, and he’d continue playing with Trane up until his death in 1967, lending his free-form squeals and sax screams to the likes of Kulu Sé Mama, Meditations and Om. As Albert Ayler, the “Holy Ghost” of the trinity, said of the duo, “Coltrane was the father, Sanders was the son.” And the spirit moved through Sanders something fierce.

Tauhid, newly released in a trio of reissues via Mexican Summer’s Anthology imprint, was Sanders’ second album overall, but the first to truly capture the whole of his potential. Playing with Coltrane, it seems, had unleashed something mighty within the 27-year-old saxophonist. He arrived at the sessions with a new sense of purpose and direction—and a willingness to let the emotion of the performance guide him. Early critical responses to Sanders’ performances were sometimes dismissive of the aggression behind his playing, but Tauhid backed up his intensity with a sense of direction and clarity, as well as a batch of incredible compositions. “Upper Egypt & Lower Egypt” is less a standalone track as it is a sprawling musical suite, a buildup from a scratchy avant garde intro into an ambient midsection and eventually a triumphant groove. Its flipside takes on entirely different directions, proving Sanders’ versatility as a bandleader. “Japan” is a brief, albeit inspirational moment of melody and vocal incantation, whereas “Aum/Venus/Capricorn Rising” explodes into a freeform blast of avant noise-jazz that doesn’t quite reach the acoustic violence of Peter Brotzmann’s “Machine Gun,” but also isn’t too far off. Taken as a whole, the three compositions on Tauhid encapsulate the whole of Pharoah Sanders, presenting his capabilities and vision all in one relatively concise package.

Jewels of Thought, his third album, heightens the juxtaposition of Sanders’ more mellifluous compositions against his most radical. Its first side, “Hum-Allah-Hum-Allah-Hum-Allah,” begins with a plea for peace and a vocal delivery from Leon Thomas that’s nearly as far-out as Sanders’ saxophone is on its flipside. Yet ultimately this composition—a soulful call for understanding and love—is among Sanders’ most hypnotic grooves, a breathtaking 15 minutes driven largely by Lonnie Liston Smith’s stunning piano. The two-part “Sun In Aquarius,” by comparison, is a furious exploration of dissonance and abrasion. Its first movement is darkly atmospheric, driven by Smith’s menacing stabs of piano, a far cry from his glorious chords from “Hum-Allah.” Yet the second half undergoes a thrilling transformation from free-jazz screech back to soul-jazz transcendence and eventually some strange hybrid of the two. It’s not Sanders’ most immediate composition, though as one of his most challenging it warrants revisiting and reexamining.

Deaf Dumb Blind (Summum Bukmun Umyun) is the most breathtaking of the three. Released in 1970, it began what was ultimately a decade of profound exploration for Sanders, yet it also contains some of the best ensemble performances. The title track is a rollicking, percussive groove with heavy African influence. Its name is a phrase from the Koran, applied here as a likely political statement amid the rise of Black Power and the Nation of Islam. Yet this 21-minute jam session is so vibrant and melodic, so joyous and exciting, it’s hard to make sense of anyone being willfully blind to its power. By contrast, “Let Us Go Into the House of the Lord” is less about movement than it is about unity. The composition is less propulsive, but it feels deeply spiritual in a way that all of Sanders’ best compositions are, evoking a wide breadth of human emotion in one deeply affecting stretch.

Pharoah Sanders’ music is spiritual, and it’s also political. It’s soulful, yet it’s deeply anguished. There is sadness and pain in his music, and yet it overflows with joy. It’s beautiful, and somehow also chaotic. This duality of Pharoah Sanders is what has made and continues to make his records and performances so important. He encompasses the oneness of human experience in his music, and for all of his avant garde experiments, it’s easy to find the feeling and the realness therein. Released during highly turbulent times and following the loss of his friend and mentor, these three Pharaoah Sanders albums are reflections of a man finding his way through the darkness and making it his mission to put something beautiful back into the world.

Similar Albums:

John Coltrane – A Love Supreme

John Coltrane – A Love Supreme

Kamasi Washington – Harmony of Difference

Kamasi Washington – Harmony of Difference

Tony Allen – A Tribute to Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers

Tony Allen – A Tribute to Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.