Os Mutantes’ debut album is a perfect distillation of chaotic joy

In Brazil in the 1960s, playing rock ‘n’ roll was dangerous. With the installation of a military-led government in 1964 following a coup d’etat, censorship became the norm, the country’s leadership cracking down on any kind of dissent as a matter of state policy. As with any authoritarian rule, however, there became a growing opposition to General Costa e Silva’s dictatorship, led by students, laborers and Marxists. Most subversive of all were the musicians. The growth of the Tropicália movement created an artistic revolution that made the resistance coalition uneasy as much as it did the government. By the end of 1968, it imposed the crippling AI-5 bill, which called for a blanket censorship on politically subversive music, as well as other far reaching consequences such as suspension of habeas corpus and the dissolution of the National Congress. The result was an extended period of cultural oppression and artistic exile.

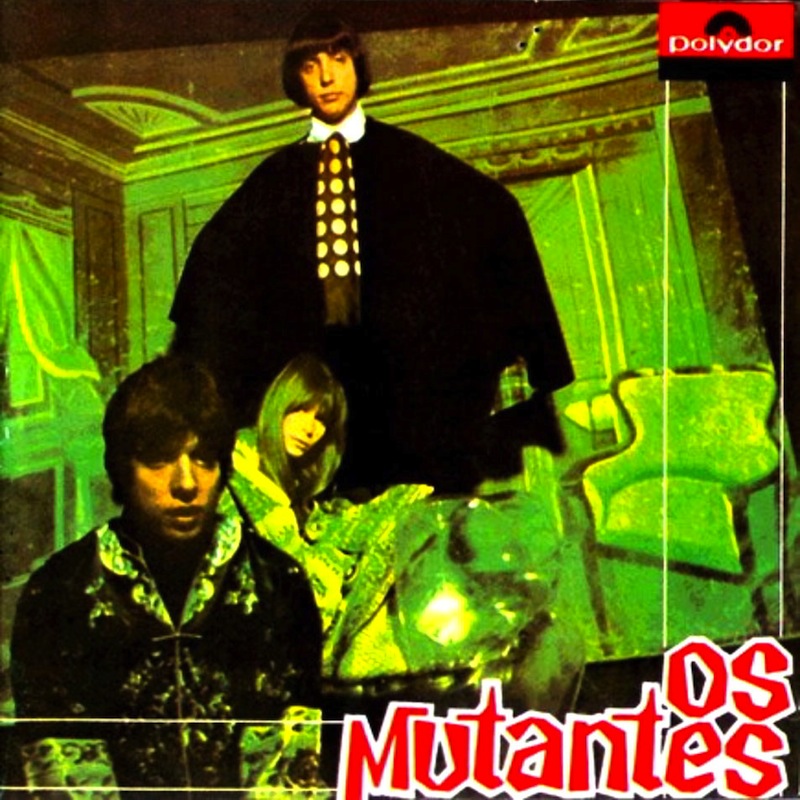

The Tropicálistas, in other words, were outlaws, protesting iron-fisted rule by making strange, colorful, psychedelic music that was unmistakably Brazilian. Led by artists such as Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso, Tropicália exploded into public consciousness in 1968 through a vibrant fusion of classic Brazilian sounds like samba with psychedelic rock and avant garde performance art. And no artist in the movement created as perfect a full-length document of Tropicália’s aesthetics and ethos as Os Mutantes, a trio of brilliant young pranksters comprising brothers Sérgio Dias and Arnaldo Baptista and Rita Lee.

Os Mutantes’ self-titled debut album, released 50 years ago, sounds like few other records. Even among their peers, it stands alone, more scrappy and mischievous than Gal Costa, more grimy and garagey than Caetano Veloso, and more unabashedly pop than Tom Zé. A melting pot of influences, styles and sounds, Os Mutantes’ first album compiled tracks written by a number of prominent Brazilian songwriters, including Jorge Ben (“A Minha Menina”), Caetano Veloso (“Baby”) and Gilberto Gil, as well as a pair of international pop covers: Francoise Hardy’s “La Premiere Bonheur du Jour” and The Mamas and the Papas’ “Once Was A Time I Said,” here titled “Tempo No Tempo.”

It’s also an absurdly fun set of songs. With “Bat Macumba,” written by Veloso and Gil, the group turn a repetitive yet constantly ebbing chant and homemade fuzzboxes into a jam-session centerpiece. “Senhor F” is something like a jazzy TV theme song, while “Adeus Maria Fulô” finds one of the deepest yet illusory grooves on the record, a hand percussion rhythm doing double duty as a bassline. “Trem Fantasma” showcases the full spread of the band’s vision, from a hazy vortex of flutes into a colorful, brassy pop strut. Though no song from the album has gotten as much mileage as “A Minha Menina,” which turns Jorge Ben’s samba into a rollicking psych-rock anthem that radiates utter joy, from the manic opening yelps to the wild guitar riffs propelling it. It lived a short life in a McDonalds commercial decades after it was released, though even that couldn’t sap it of its cool. Music this inspired and free can’t be replicated or reined in.

”We were so innocent back then that we weren’t even fully aware of what we were doing, and that gave our music a tremendous honesty,” Lee said in a 2001 New York Times interview. “Everything we did was spontaneous and natural in a way that is simply not possible today, and I think that people have come to value that and respond to it passionately.”

The brashness and unpredictability of Os Mutantes’ music could be partially attributed to their youth. At the time of their debut album’s release, Arnaldo was only 20 years old and his younger brother just 18, while Rita Lee was just 21. But for a trio of scrappy kids, they showcased musical chops beyond their years. The Baptistas came from a musical family, their mother a concert pianist and their brother Cláudio responsible for building their guitar, Guitarra de Ouro (“Golden Guitar”). Lee, meanwhile, was fluent in five languages and taught herself drums, though she avoided following her mother’s path as a pianist. The trio met at a battle of the bands, and their name (“the mutants”) was decided shortly before they made an appearance on Brazilian TV.

Os Mutantes weren’t overtly political in their music. Certainly not by the standards of Bob Dylan or Sly and the Family Stone. In a sense, the activism in their music came from the act of making music that sounded radical. But they also wrote one of the most poignant and anthemic protest songs of Tropicália’s moment, “Panis et Circensis,” which (though misspelled) translates to “bread and circuses.” A playful critique of the Brazilian government complete with fanfare, an opening military march and a childlike melody, the song is a sort of anthem for the Tropicália movement, even lending its name to the compilation Tropicália: ou Panis et Circensis, released the same year. But the band—who infamously backed Veloso during a notoriously volatile performance at the 1968 International Song Festival in Rio de Janeiro, met with great hostility—largely avoided the consequences that befell some of their peers. Veloso and Gil were jailed before being exiled to England until 1972, and another prominent songwriter, Chico Buarque, left the country voluntarily as a result of the oppressive government regime.

The Baptistas and Lee were lucky in that they never faced prison time or were forced to leave their home, but they were also clever. They knew the risks of playing the music that they did, and they found ways to circumvent authority.

“When we were kids we had to face in Brazil a lot of serious repression and we were under severe military government—a lot of people being killed, a lot of people tortured; it was heavy, very heavy. And nasty,” Sergio Dias said in an interview with Impose. “But when you are a kid you have this thing, this war inside, this delight of going against whoever says that you can’t. And we were damn lucky that they didn’t arrest us or torture us or do anything like that because we probably would have lost faith.”

”Our whole thing was playing pranks and defying authority, but you had to be careful in those days because friends were disappearing or being forced into exile, and the cops would often come in and bust up our shows,” Lee said. ”We had to be creative but evasive to avoid the repression, and so we’d tell each other, ‘Let’s make this song complicated so that nobody understands it.”’

Not everyone got Os Mutantes. In fact, the band made sport with their Tropicália peers to see who could provoke the most boos from an audience. And when Veloso introduced English audiences to the band’s music during his exile in London, they often dismissed it as a “Beatles rip-off.” But decades after its release, Os Mutantes’ debut album earned a new audience. Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain was famously a big fan, having once sent a letter to Arnaldo Baptista requesting that the band reunite. Had he lived another 15 years, he would have gotten his wish, as Sérgio Dias Baptista (with Arnaldo briefly) revived the band, which is still active now. In 1998 Beck released Mutations, its name inspired by the band as well as its lead single “Tropicália,” which paid tribute to the movement’s sounds and aesthetics. One year later, David Byrne’s Luaka Bop label gave the band a proper U.S. release with Everything Is Possible, a kind of hits collection introduction to the band’s music.

After 50 years, it’s hard to pinpoint an artist that so brilliantly captures the fun and mischief of Os Mutantes on their first LP, an utterly perfect distillation of chaotic joy. Though their influence is undeniable, not only in the music of the aforementioned Beck but with artists such as Stereolab, The Fiery Furnaces, Soundcarriers, Broadcast and their closest modern analogues, Brazil’s Boogarins. It’s music that still sounds revolutionary because it captures young people in search of something they didn’t know they were looking for. It’s untainted by industry trends or expectations, brilliant because it isn’t trying to be. It’s music that at the time nobody would ever think to make, which makes it all the more miraculous that they did.

As Rita Lee once put it, “Why be normal when you can go where the nuts come from?”

***

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.

Great !!!!!