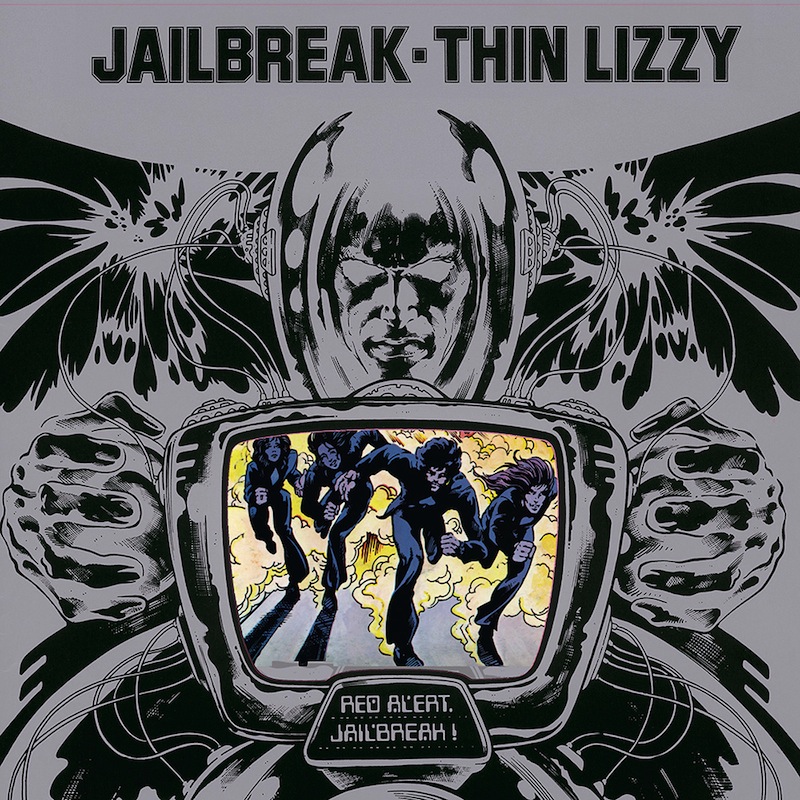

Thin Lizzy : Jailbreak

There are certain bands, albums, or songs that get attached to moments of your life or people you know. Matthew Sweet’s Girlfriend, for instance, is inextricably linked to middle school when, for all my awkward charm, I couldn’t seem to find a gal who’d even give me the time of day. Every time I think about an old girlfriend in high school, she’s married to the Smashing Pumpkins catalog from Siamese Dream through Adore; and fittingly, after a foul break up, I finally got over her with the Pumpkins swan song Machina, sandwiching her between the Pumpkins’ alpha and omega. My friend Jim is attached to Nirvana’s output. My stoner artsy friends who did all those pen drawings with mushrooms and pot leaves hidden in the line work are in league with Primus. My old buddy Nate, for better or worse, claims Tool in my mind.

That said, there is actually one album that will always epitomize my group of close friends and me in the latter days of high school. During that time when boys turn to young men (in age only) and before the old bonds of fellowship would soon be severed by college, more serious relationships, the souring of old alliances, and the fermenting of petty grudges, the album that will forever be locked to our merry band is Thin Lizzy’s Jailbreak.

Jailbreak was an album we could all enjoy on afternoon treks to the beaches of Santa Cruz, post-coast journeys for pasta and pastries at Gayle’s Bakery and Roticceria, late night sojourns to The Donut Wheel, or random trips to record stores and around our wicked, boring, suburban nightmare of a little city. There would be little argument about it. Our passive aggressiveness toward our differing tastes in music (for them, Jimmy’s Chicken Shack; for me a burgeoning love for The Boo Radleys and Belle and Sebastian) could be pacified by the smooth sounds of that great bass-wielding peacemaker and Thin Lizzy frontman Phil Lynott.

One of the things that always struck me about hard rocking Dublin quartet’s sixth and best album was the eponymous narrative in its liner notes. Describing some clash between a despotic figure known as the Overmaster, the oppressed masses, and some heroic guy known only as The Warrior, it conjures up images of pulpy sci-fi comics telling thrilling dystopian tales. It leads one to infer that Jailbreak is the apocryphal revolution-inspiring recording of the four escapees from the story, recorded in the Rampic Buildings after eluding the robot trackers and attack dogs of the tyrannous ruler of religion and the media.

The thing is, only a few of the songs address the narrative, some more obliquely than others. There’s the tough-riffing “Warriors,” a song whose heart is ruled by Venus and whose head is ruled by Mars; and whose raison d’etre, apart from being an arse-kicking blast of hard rock, is to point that The Warrior is rough, tough, and don’t take lip. There’s the closing battle hymn “Emerald” describing a warring band razing the land over the dueling, squealing solos of guitarists Scott Gorham and Brian Robertson. There’s the rallying call of “Fight or Fall,” Lynott here calling to his brothers to take a stand and fight together and for one another. Yet its tone is a lot more quiet and meditative than your usual call to arms, Lynott and Robertson’s smoky voices over a soft, soothing melody humming and ooh-ing together, exchanging conciliatory, soulful lines as the songs fades away. And of course there’s the masterpiece of a title opener, “Jailbreak.” The song’s main riff is a tough and catchy crunch that all three or four chord songs should aspire to. A wah-wahed guitar ushers in Lynott’s lyrics mostly consisting of warnings to chumps who get in his way and a come hither to good-looking females. The assault of the verse opens up to the sustained power chords and en masse vocals of the chorus. It’s a feel good song for folks feeling the rush of hooliganism or, I suppose, an anthem for antagonized convicts held in shackles by the oppressive regime of a science fiction ruler.

The other songs, which don’t adhere to the sci-fi narrative, as cool as they are, don’t make me want to fight the mighty Overmaster. Yes, a song like “Running Back” — telling the story of a guy singing songs of about a girl who jilted him whom he’s not completely over — doesn’t make me want to take up arms. Instead, “Running Back” makes me just want nod and whisper, “You tell it, Phil,” after every few lyrics, a wry smile on my face when I hear the whisper of sax in the background. The same goes for “Romeo and the Lonely Girl,” with its weeping, trilling solo and its sing along-inducing chorus, “Oh, poor Romeo / Sitting out on his own-ee-o .”

Apart from “Jailbreak,” there are two other Thin Lizzy essentials on this album. First and foremost, there’s “The Boys Are Back in Town,” a song heard everywhere from beer commercials to sporting events to high school reunions to Toy Story movie trailers. Originally conceived as a song about a Vietnam vet’s return from the war to be titled “G.I. Joe is Back in Town,” Lynott shirked the war theme and shifted the song’s center to a group of friends getting together to paint the town red. Gorham and Robertson’s melodic leads and fills saturate the song, Lynott’s bassline hopping and skipping around like an elated lush having a good time, its head-bopping rhythm all held together by Brian Downey’s drums. Then there’s “Cowboy Song,” which, if it weren’t so giddy, joyous, and well put together it would just be plain ridiculous. This tale of a lonely rodeo cowboy with a certain female on his mind initially recalls images from a John Ford movie or Winslow Homer painting. Yet “Cowboy Song” soon erupts into a southern rock anthem about bucking a bronco and spinning around till you hit the ground. When the crunch comes on and the trilling, soaring solo takes hold, the august Ford cowboy gives way to an image of Lynott in black and white cowhide chaps and a Stetson perched on his afro.

I remember one last summer in San Jose before heading off to college, those last warm months driving around with my friends doing nothing of great consequence. After spending a night at the beach playing guitar around an expertly made fire, our clothes smelling of soot and our hair damp from the cool ocean spray, we popped in Jailbreak and headed home, huddled in a Civic hatchback with the heat on and the windows partially rolled down. Nodding along to “Jailbreak” and pumping our fists to “Warriors” in a manner that would earn the approval of that bad ass interdimensional savior, we were soon swept up in the good time feelings of “The Boys Are Back in Town.” I don’t know who started it or why we decided to do it, but we were overtaken by the uncontrollable urge to whistle along with the song. We didn’t coordinate it properly. Rather than assigning the guitar, vocal, and bass parts to different people, we just put our own lips together and blew with abandon. We never quite got past a few seconds of the song because, as we learned that night, five people whistling at once is hilarious. Try it some time and try not to laugh like a lunatic. It’s one of those moments I can look back on and say, “Yeah, those were the days”; it was the memory that, more than any other instance of listening to Thin Lizzy in the car, attached the band to my friends and even that entire summer before we went our separate ways.

Even if I never see any of those boys ever again, which may sadly be the case for some of them, I still have those whistled minutes in a summer Civic ride, the wind in our faces from cracked windows, the heat shooting at us from the AC vents, and all of us unable to purse our lips for more than a few seconds before laughing long and loud over Lynott; tears rolling down our faces, cheeks tight and aching, our mouths straining to form an “O” so we could attempt whistling again. And I’ll remember that, and I’ll remember them, and I’ll remember Jailbreak as a part of us all. That evening, the music sailed out into the night then upwards towards the skies, traveling on that thin border between reality and imagination, encroaching adult responsibilities and dwindling youth; that thin border between the fondest of memories and the fact I may never have another moment quite like those days, the days when we boys were still boys and we were all still in town.

Similar Albums/Albums Influenced: Ted Leo & The Pharmacists – Hearts of Oak

Ted Leo & The Pharmacists – Hearts of Oak Bruce Springsteen – Born to Run

Bruce Springsteen – Born to Run AC/DC – Back In Black

AC/DC – Back In Black