Out of Range: Part One—Deeper Than Inside

Out of Range is a five part, in-depth exploratory series that covers the the history of emo. From its first wave to its current revival, on to the impact of the word itself on language and fashion, it’s a primer for understanding the growth of a genre in its totality, alongside the technologies and changing cultural values that allowed it to flourish.

The following is part one of a five-part interview series with Tom Mullen of Washed Up Emo, a curator of emo history and, above all, an educator who has kept the dream of the genre alive through good times and bad times alike. Tom was gracious enough to offer his insight about the genre including its controversies and hidden histories.

Chapter 1: Deeper Than Inside

It has been said that we don’t study history to learn from the past; we study history to learn about the present. In music history, this concept can’t be underestimated. Before we begin to learn about why, when, or what “emo” is, we have to understand where it came from and the corresponding climate politically, culturally and technologically that helped embed it into the lexicon of music history.

All movements—big and small, loud and quiet—come in waves. For the purposes of this series, we have to settle on what these waves of music actually are. Everyone has their own beliefs on what constitutes a wave with different metrics guiding their standards.This series is working on a mostly decade-by-decade basis: The first wave is from 1985 to 1990. The second wave, or the golden era, is from 1990 to 2000. The third wave, what most readers are going to be familiar with, is from 2000 to 2010. The revival, or fourth wave, starts in 2011 and runs to the present. Each one of these is going to be explored in some capacity, some more than others. Some will be praised. Some will be admonished.

These four waves, when combined, comprise a cycle, which follows as thus; it begins with earnest thoughts, rises to prominence, is commodified and returns once more to a state of integrity. In a sense, perhaps due to the nature of any artform meeting commercialization, emo in this sense is a lens into the world of musical cycles and associated trends. Out of Range is a case study—if you will—in selling out and finding (and sometimes re-defining) integrity in a constantly evolving landscape culturally.

So let’s start at the beginning.

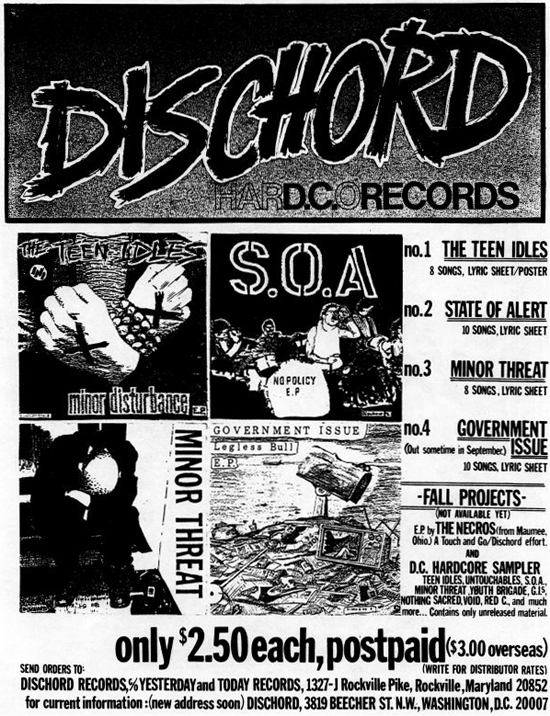

Washington, D.C., 1984. Ronald Reagan is president. There is misery afoot for the working class, a lot of people are without work. Like an unclean wound, it is the perfect breeding ground for a virulently aggressive, politically driven punk scene. However, it’s also ripe for permutations, primed for changing not just the themes and styles of the music, but the expressive lyrical values of the music as well. Rites of Spring, formed by members of the independent Dischord label, in their efforts defined an aural dichotomy that lingered between melancholia lyrically and abrasive punk sonically. This was new, this was important, and everyone that heard it, recognized it. The band played 15 shows before disbanding, with former members later helping form Fugazi. What was important, beyond the sheer visceral impact of their shows, was the audacity of their experiment both musically and philosophically.

What grew to define Rites of Spring and those that followed in their wake, was a genre designation that was a shameful, dirty word from the moment it was conceived. “Emo” or Emotive Hardcore or Emocore, the name in any form was ill-fitting. Perhaps the reaction was due to the contradiction that all music is inherently emotional, perhaps it was read as an attempt to appropriate the sound of what was a close-knit scene. Either way not a single soul alive within the scene at the time felt the term was appropriate. Ian McKaye co-founder and owner of Dischord records as well as vocalist of Embrace and Fugazi, stated “We were punk bands. We never thought about calling ourselves anything else. ‘Emocore’ was purely derisive, it was meant as a put down.” (Bryant) Or to be a lot more blunt, MacKaye later stated “‘emo-core’ must be the stupidest fucking thing I’ve ever heard in my entire life.” (Redding)

Perhaps the myth or rather, debate about the origins of the word is just as compelling as the music itself. And across the corners of the internet, this debate rages on. Maybe, it doesn’t matter though. Theories range from its origins at the hands of music journalists at Thrasher, to fans of the bands and members of the local Washington scene, to members of the bands themselves, with Brian Baker of Dag Nasty being cited as potentially coining the phrase according to MacKaye. What does matter is what it grew to define, and what later it could no longer possibly stand for.

Emo, even from its inception, was already about carefully decided boundaries, both by those who created it, ad those who followed it with equally intense passion and devotion. A devotion that still lingers in today’s world and is still plagued by the connotations associated with the word that invoke reluctance and hesitance. But why? That’s another mystery in its entirety, but it could stem from a lot of reasons. It could have been the perceived masculinity of the early hardcore and punk scenes, it could have been an association with weakness or sensitivity that wasn’t appropriate to engage with openly, but it’s obvious that the intent was there. Yet, maybe this conflict, a simultaneous love and hate for the term itself helped it to propagate, the self inflicted irony being somehow equal to the sincerity that helped create such open music.

It did grow. Emo’s genesis doesn’t just lie with Rites of Spring. It would be improper to burden the birth of the genre to just one area or locale. In 1986, California gave the scene Jawbreaker. Chicago’s songwriting brothers Mike and Tim Kinsella formed Cap’n Jazz in 1989, eventually causing the genre to take hold throughout the midwest. In 1986, Maryland’s Moss Icon fused rampant experimentation and a passionate obsession with the spoken word, an effect that would later become a fixture within the genre.

Given such a tremendous limitation in terms of distribution models of the time, it’s no understatement to say that these bands worked against immense limitations. It’s difficult for us now with the immediacy and accessibility of our consumer abilities to understand the limits of the ‘80s. Once more, we’re looking backwards to understand the present, and processing how technology changes our ability to communicate and disseminate music that we are passionate about. All artists work within their given spheres of technology, in this case cassettes, vinyl and (at the time) the prohibitively expensive format of CDs.

Emo bands in the ’80s even those signed to independent labels found strain on their abilities to reach outside their prospective spheres being limited by communication. There was no internet. There were zines, there were flyers about local shows, and there were catalogues of independent labels found in music shops with mail order options.

Alongside a drastic difference in actual physical media, culture and perceived mainstream taste had not yet accommodated truly alternative music yet. The vanguard of music critics while aware and accepting of its presence, could not find a means to truly promote the underground in any meaningful capacity.This struggle however helped foster an identity for the movement that would signify perseverance, and integrity. Something that it would struggle with as it matured, an ethos that as it moved forward into its second wave, would be tested.