Revenge and Guilt: Elvis Costello’s My Aim Is True at 40

There was no way of knowing what Elvis Costello would eventually become in the summer of 1977, when he released his debut album My Aim Is True in Britain. Even as it became, as a 1979 Creem article says, “the all-time biggest selling ‘import’ of this decade” and spurred a US release in December 1977, there was scant hint of what he’d soon inflict on the mainstream rock discourse.

I certainly had no idea he’d eventually become my favorite musician of all time, nor about the several reasons why.

Not long after Elvis No. 1 collapsed for his last, Elvis Costello launched on a label, Stiff, that celebrated not just its lack of pretense, but its comical swing in the opposite direction via pub rock and early punk. My Aim Is True was recorded with, essentially, a pickup band that sounded very little like his subsequent group, The Attractions. Although it was willed into prominence by excited critics and a remarkably high-attention audience, My Aim Is True retains its scruff. Were it not for Costello’s well-built ambitions, it still could have been a single unit of mania from a brief but emboldened era in rock—like Steve Forbert, Bram Tchaikovsky, or the other hordes of undernourished power pop bands of the time.

What we didn’t know was that Costello would be prolific and directed, and that his musical IQ was so advanced, his range of reference so broad. If nothing else, the next 40 years of his career is a good argument for his being the greatest pop music fan who ever existed (a major reason for my own feelings about him). Knowing that now, it’s easy to see how My Aim Is True was a blueprint for what he’d construct afterwards.

After being just enough of a squeaky wheel to Stiff Records and Nick Lowe to get his songs taken seriously, the 22-year-old Costello was brought in as a songwriting prospect for other artists, specifically Dave Edmunds. With Lowe producing, Costello recorded the songs that ultimately became his full-length debut in 24 hours over six sessions, while calling in sick at his day job operating the room-sized IBM 360 at a beauty company.

Costello met up with Clover, a Marin County country-rock band who was flown to London by Stiff executives, ostensibly to determine their signability. Clover wound up having a modest influence on the pop landscape after their dissolution: Three members went on to form Huey Lewis & the News (including Lewis), lead singer Alex Call went solo and wrote the enduring Tommy Tutone hit “867-5309/Jenny,” and guitarist John McFee continued his in-demand session work and joined the Doobie Brothers. (Lewis and Call, Clover’s two singers, were not on Elvis’ album.)

The upshot of working with this American version of a Stiff pub rock band was their unfamiliarity with some of Costello’s more outré influences at the time. “On ‘Waiting For The End Of The World’ I had in mind the Velvet Underground,” Costello told Musician’s Bill Flanagan in 1986. “I don’t think Clover had ever heard the Velvet Underground, so it came out sounding nothing like them, which was good.”

Recorded well before Costello assembled the Attractions, My Aim Is True has a rougher sound, informed by both the schedule and the limited capacities (and, most likely, budget) of the studios they used. Overdubs were, if not forbidden, at least discouraged. When I first bought it—it was not my first Costello album, probably fourth or fifth—I thought it wasn’t mastered very well. This was the assumption of a teenager who had no idea what the mastering process entailed.

There are other differentiating factors to My Aim Is True, especially compared to the quick rush of Costello albums that followed. With Clover backing him up it’s his most American-sounding album prior to King of America, and Costello’s singing followed suit. “Blame It On Cain,” “Sneaky Feelings” and “Pay It Back” were all set to Southern rock and soul shuffles, “(The Angels Wanna Wear My) Red Shoes” was a very unsubtle callback to the Byrds, and Costello has openly admitted that “Alison” was fashioned from the chorus of the Spinners’ “Ghetto Child.”

If Bob Dylan, as I pedantically preach, expanded the vocabulary of rock music, Costello’s first gift was fleshing out more precise details and finding more to fill in.

None of this was directly related to the punk rock that was accelerating in England at the time, but that didn’t stop the fifth column from calling Costello punk. They weren’t entirely wrong if you stretch the definition of punk a bit. A music journalist’s life is full of selfless, arduous labor for the greater good of the community. Sometimes they have to make snap judgments in the midst of their heroism. You understand. Excuse me, the Dalai Lama’s on the line, I’ll be right back.

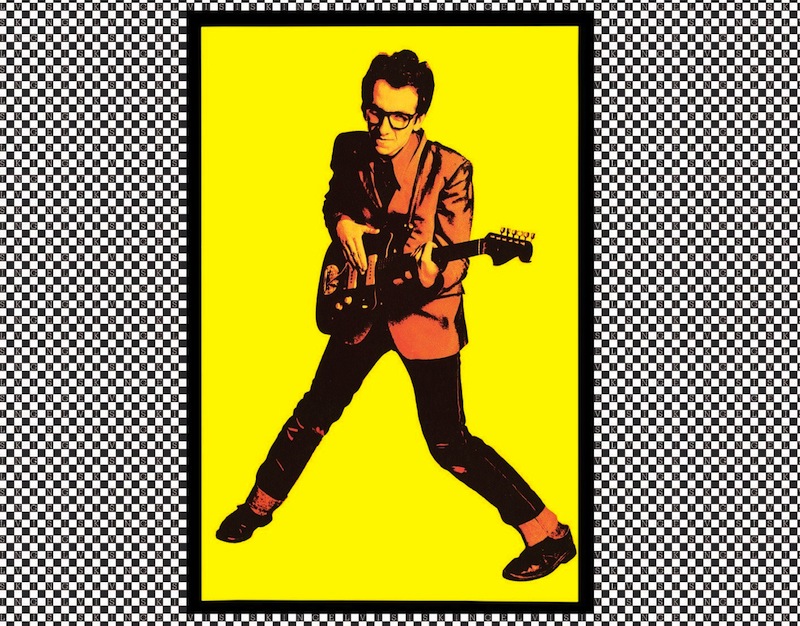

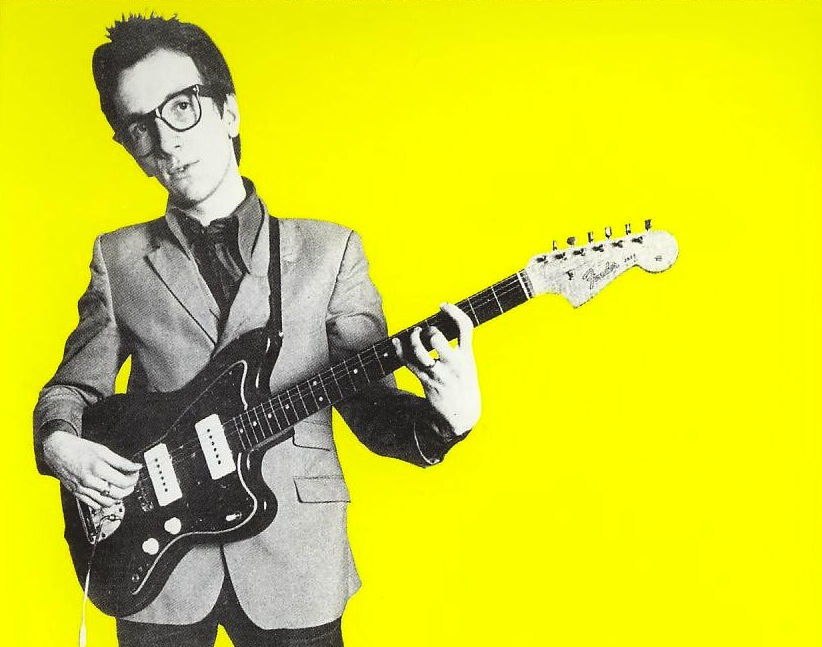

Shortcutting Costello into the punk ethos of the age may have been superficially understandable—his label, after all, had released the first album by a British punk group, The Damned’s Damned Damned Damned, also produced by Lowe. Costello’s aggressive posture on the cover shot of My Aim Is True relayed some sense of combativeness, whatever menace could be conveyed by a man in thick-rimmed glasses whose feet appear to have been installed at right angles to each other. While punk channeled discontent into apoplexy at a perceived institutional order, Costello’s discontent was more personal. It wasn’t aimed at toppling the fascist regime Johnny Rotten sang about. It existed in an only slightly less militarized zone than Buckingham Palace: the suburbs.

My Aim Is True opens and closes, at least conceptually, on the London Underground. It starts with a routine commute to the working week and ends with a routine commute to, the singer snidely hopes, the end of the world. In between are negotiations with situational, mundane white-collar life. The sexual revolution leaves one unskilled practitioner with his head in his hands (“Miracle Man”); a middle-class by-product thinks the correlation between the Protestant work ethic, money and religious faith might not be that valid or rewarding (“Blame It On Cain”); an old wannabe boyfriend revels in, but then empathizes with, the slowly unraveling housewife life of the former object of his affection (“Alison”); a girl gushes over a film-noir similarity to an actual man (“Watching the Detectives”); a jealous man overhears his ex’s sexual escapades and gets really, really angry (“I’m Not Angry”).

None of these topics were covered in much detail before. If Bob Dylan, as I pedantically preach, expanded the vocabulary of rock music, Costello’s first gift was fleshing out more precise details and finding more to fill in. You’re not just famous, “your picture’s in the paper being rhythmically admired.” Your husband didn’t just drift away, “he left your pretty fingers lying in the wedding cake.” You’re not just eavesdropping on your ex’s sexual encounter, you hear her “calling his name, (you) hear the stutter of ignition.” You’re not just taking the subway home after an enervating week—you share a train with an annoying journalist, a gravity-challenged hippie with no direction, and a harried (possibly imagined) wedding party escaping the unforgiving public eye, and yet you’re still bored.

These are details that don’t come from basic sensory perception. They come from the need to make a new lexicon for the standard pop music subjects of love, sex, dancing, the working life, total bullshit and institutionalized boredom. They were specific, and once Costello set them up as he did on his first three albums, it’s easy to see how he could go wherever he wanted afterward.

It’s a little amazing that My Aim Is True found as much success as it did with this lyrical approach, but Costello’s own sourcing for his songs reveals their approachability: “There was at least as much imagination as experience in the words of this record,” he said in his liner notes to the album’s 2001 reissue. “Whatever lyrical code or fancy was employed, the songs came straight out of my life plain enough. I hadn’t necessarily developed the confidence or the cruelty to speak otherwise.”

Oh, yeah, speaking of cruelty: Costello was pegged an “angry young man,” a descriptor I never quite got after its initial use for identifying British authors of the ‘50s (Kingsley Amis, Alan Sillitoe). Costello’s AYM bonafides were facilitated by his famous quote that his only motivations for songwriting were “revenge and guilt.” Much of his anger looked staged from this distance—pound for pound, Graham Parker was way angrier than Costello.

If the overall effect of My Aim Is True was one of disaffection, song-by-song it’s not always clear that he’s unsympathetic. The third person in “No Dancing” is watching a pub romance fall apart before his eyes, and despite its legend as a supposed murder ballad (or, my close friend Scott more correctly supposes it, a “pre-murder ballad”), I felt the net effect of “Alison” was one of solicitude. Reluctant solicitude, sure, but still legit.

Part of Costello’s technique was to hasten the maturation of the tenderized singer/songwriter format, for reasons of self-preservation. “I’ve always tended to qualify in songs,” he told Flanagan. “I never wanted somebody to point and say, ‘What a naive position!’ And I suppose in doing that I betrayed naiveté in the long run. That’s the irony of it in retrospect.”

My Aim Is True isn’t so much an angry album as it is a predisposed one, a pre-emptive admission of crushing disappointment, with occasional moments that are so not disappointing that the singer temporarily loses focus (“I said ‘I’m so happy I could die’/She said ‘Drop dead’ and left with another guy”). Perhaps it’s not piercing marketing to say, “Really, he’s not totally pissed off, not 100 percent of the time, anyway.”

It’s to the credit of the 22-year-old who picked up on these sordid truisms that his songs were critical but not depressing. Costello used the punks’ element of release and relief for more intimate situations in which mainstream artists tended to exert more caution. Personal singer-songwriters generally embraced defeated acceptance and martyrdom to stroke their images. Costello saw through that scam and explained what was really going on. On My Aim Is True, and especially its follow-ups This Year’s Model and Armed Forces, that tactic isn’t the deadening, cynical stopgap that the more amateur of punks employed. Instead it’s a real pivot toward a goal of general sanity. Punks sought disturbance of the external order; Costello wanted to rattle the internal one. He was only trying to help.

Elvis Costello’s My Aim Is True: Song By Song

“Welcome to the Working Week”

Elvis Costello’s first album starts with a fantasy sequence: A Brian Wilson-style background chorus coos as a commuter dreams of fame, wealth, admiration and copping feels. Then Elvis snaps him out of it: “Why? Why? Why? Why?” Costello talks to his commute partner about the irrelevance of the blue-collar wartime economy, his unlearned opinion about real city life, and finally the uselessness of their friendship despite their commonalities. And it takes all of 83 seconds.

“Miracle Man”

The sexual revolution of the ‘60s was great and all, but when it hit the disco era more importance was placed on performance reviews. Costello’s character, one of a rotating cast of his partner’s lovers, turns his efforts at intimacy into a slapstick routine, stumbling through physical variations with no guarantee of eventual success: “I’m the one that’s here tonight, and I don’t wanna do it all in vain.” “Sex as a commodity,” as the Mekons later described it.

“No Dancing”

Costello’s viewing the slow-motion deterioration of an unbalanced relationship in a pub, reporting back to us in the third person. It’s a cage match between egos, the boy constructing his martyr myth while his patient girlfriend hurtles towards neutrality. He can’t abide her making “a fool of him,” but we’re only hearing his side of the story: “Why can’t you give me anything but sympathy?”

“Blame It On Cain”

Costello slyly wraps a pitchfork of various stressors into one bundle, challenging the religiosity of duty and the interconnected machine of money, family and godliness. Kicking that facile construct to the curb, he just shrugs his shoulders and blames the book of Genesis’ first passion killer for his current status. Nobody took the time to hear Cain’s side of the story, after all; Costello may as well be the first to ask. This is one of My Aim Is True’s most sinisterly effective songs.

“Alison”

Long before the final episode of The Sopranos there was the mystery of whether or not the singer of this song kills Alison. Costello denied this intent in his memoir Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink, and in all honestly homicide doesn’t fit into the narrative arc of “Alison.” Yeah, he might be savoring a miniature revenge that happened without his direct input, which is often more deeply satisfying than having something to do with it. But he fights with that tendency and finds himself dealing with a surging empathy he didn’t expect. It would be contrarian to whack her at this point. But I’m no David Chase. Or Nick Cave.

“Sneaky Feelings”

A song that borrows from Smokey Robinson’s compact classics about knotty romantic situations, a business complaint about risk aversion. The singer stays within his safe zone and nourishes only what he can control, but sooner or later—probably later—he’s not even going to have that anymore. But in contrast to most of the other songs on My Aim Is True, there’s implied hope in the end.

“Watching the Detectives”

Recorded with members of Graham Parker’s band The Rumour and featuring the first appearance of Attractions keyboardist Steve Nieve, “Watching the Detectives” works as simple mood establishment. It can get by on Costello’s list of details alone and the cutting threat of his guitar hook. He’s exasperated by his partner’s TV habit and her glorification of male icons who technically don’t exist, and he rattles off all the visual clichés he knows are coming. But who needs life skills when you have Stu Bailey, or Kojak, or Frank Drebin?

“(The Angels Wanna Wear My) Red Shoes”

Having dashed “Red Shoes” off in around 20 minutes, Costello told Bill Flanagan “Red Shoes” was about the “compromise of age.” There’s a lot about the narrative that’s difficult to pin down, but the looming threat of getting older in the social order is something that usually hits when drinking age rolls around. It’s the one song on My Aim Is True where the singer seems perfectly willing to indulge a happy fantasy, but why were the angels were so desperate to begin with?

“Less Than Zero”

Oswald Mosley was an anti-Semitic leader of the British Union of Fascists and the Union Movement who made a half-hearted shot at clearing his name on the media in the ‘70s, but only resurfaced old, mortifying wounds. Costello, in his debut single, found no point in countering Mosley’s arrogant arguments. Instead he wrote an editorial cartoon with Mosley engaging in a variety of moral perversions and homicide. You could call it fake news, but back then it had more cachet. In the end the only thing the singer finds Mosley’s TV show good for is drowning out the sounds of him and his girlfriend on her parents’ couch. Those were the days.

“Mystery Dance”

The first song Costello put on tape subverted old time rock ’n’ roll and its hormonal secretions by highlighting a particularly clumsy first attempt at sex. Special appearance by Romeo and Juliet, fully rehabilitated but still too antsy for their own good.

“Pay It Back”

Similar to “Blame It On Cain,” here Costello doubts the economic system but leaves godly destiny out of it. The suburban career track, even with all its security and high-end staplers, offers little to Costello’s narrator and could have adverse effects on his personal life: “They told me everything was guaranteed/Somebody somewhere must have lied to me.” But when he sings “One of these days I’m gonna pay it back,” it’s not initially certain whether he’s talking about old debts or revenge. They may be the same.

“I’m Not Angry”

The second-to-last song on the album set up the direction Costello was about to go with The Attractions and This Year’s Model. The protagonist is pretty lousy at denying his sexual jealousy, but he does convey pretty effectively that there’s not much left in the suburban working-class division worth discussing. He was close to ending his stint at the “vanity factory,” and the city and all its more lifelike melodramas were just a few train stops away.

“Waiting For the End of the World”

As a kid I thought this song was about a bus of apocalyptic Jesus freaks. In actuality it’s one last account that takes place on the train back to the suburbs. A mechanical breakdown hushes most of the passengers, but then it gets fixed. There are individual characters who give the ride a little color, but they’re processed out the minute they disembark. At the end of the ride there’s nothing left except Armageddon, but who knows when the electrical union will finally get their shit together for that one? Man makes plans, God watches Love Boat reruns. What else is new?

Paul Pearson is a writer, journalist, and interviewer who has written for Treble since 2013. His music writing has also appeared in The Seattle Times, The Stranger, The Olympian, and MSN Music.

Frank Drebin? Nice.

Great piece of perceptive journalism.