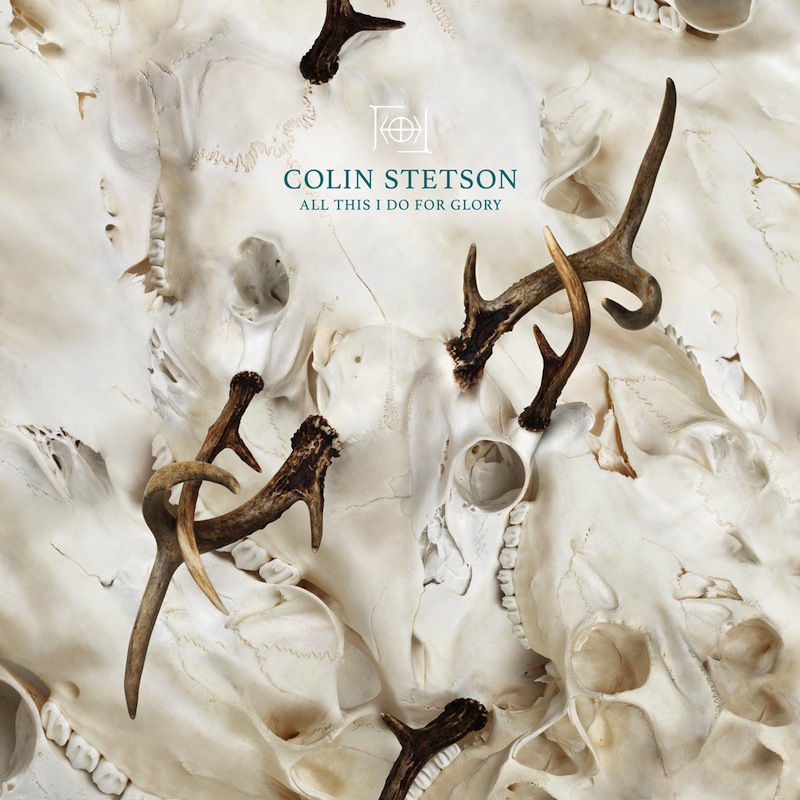

Colin Stetson : All This I Do For Glory

Colin Stetson’s solo work can be slotted, so far, into two rough groupings. There is the avant-garde and technical wing, home to his New History Warfare series and his duo album with Mats Gustafsson, and then there is the lyrical wing, home to his reimagining of Henryk Gorecki’s third symphony and most of his session work with such indie rock illuminaries as Bon Iver, Tom Waits and Arcade Fire, as well as his recent duo album with Sarah Neufeld (also of Arcade Fire). These wings collapse if you interrogate them too far. His technical work tends to sit closer, perhaps, to Steve Reich’s ultimately very sonorous and harmonically consonant form of experimental 20th century classical composition, never venturing as far afield as an Ornette Coleman or Peter Brotzmann. Likewise, even his melodic work is replete with heavily technical playing merely sublimated to a textural or melodic end, burying the demanding nature of the lines and playing in their role supporting the song.

As a result, Colin Stetson’s solo recordings tend to sit in a difficult to classify middle-space. Tendencies of pop, jazz and orchestral music are blended with the avant-garde techniques, foregrounding them less to shock the audience with sheer technical ability but more to offer as a centerpiece around which melodic, harmonic, timbral and architectural conceits can enjoin themselves in orbit.

All This I Do For Glory is easily the most decentered of Stetson’s work in recent years, due largely to forgoing a clear conceptual pin to hang his hat on compositionally. This is not necessarily a drawback, however; the result of this aimlessness is a broader sampling of Stetson’s capabilities and finally seems to be the trick to allowing him to bust out of the perceived pigeon hole of pop-avant-garde jazz (if you can imagine such a thing). The first track here reads more as R&B rescored for solo sax; we get two technical architectural pieces; there’s an out-and-out contemporary classical piece scored for solo saxophone followed immediately by a micro-tune of industrial akin to Author & Punisher’s unique, visceral and mechanical take on the genre (fitting, given Stetson’s chosen technical and, let’s say, somatic direction). All of it closes out with a lengthy programmatic epic, the closest something like this could come to prog.

The opening track of All I Do For Glory finds Colin exploring what feels like an R&B dirge. His playing is substantially more rhythmically-oriented, interested less in the pure architecturalism of the clacking of keys in sound of the chest and more in trying to point those rhythms toward some end. The industrial/R&B hybrid of Bon Iver’s recent work, on which Colin also lent his saxophone, seems to be a touchpoint here, sublimating what would elsewhere be technically impressive feats into an almost sexy number.

The next two pieces find Stetson exploring architecturalism a bit more purely. Hints of his time rescoring Gorecki appear and color the image of the opening track; there is a distant menace here, a haunting. It becomes apparent about halfway through the album that a moodiness has breached Colin Stetson’s playing and nestled itself in his hybrid humming into the reed. This is fitting and fair; he’d been toying with images of ecstasy and darkness for some time, the pure elegy of his duo record with Neufeld and his rescoring of Gorecki serving as almost on-the-nose extensions of those ideas he clearly saw potential within his own playing but had not yet taken center stage.

The fluttering “Spindrift” is the most overly neo-classical piece on the record, fluttering against the ear like a flock of birds. There’s little in the way of development, instead acting as an ambient programmatic piece. What is most surprising about this piece is how it feels so little like a 21st century avant-garde piece, like so much of his other work sometimes gets labeled, and very much like a 21st century recording of a traditional classical or romantic piece of the 1700 or 1800s. It’s a surprising move, to make a work so directly in that school, but feels like a necessary one; it is perhaps the biggest breath of fresh air on the piece, and is so refreshing precisely because it is balanced against other dissimilar pieces.

The final two tracks form a strange pair, the ultra-compact “In The Clinches” clattering like a city alleyway before a sharp stop and album closing epic “The Lure of the Mine” picking up a similar motif in calmer format. The effect is almost that of an unbroken piece; “Clinches” acts both as a palette cleanser to the preceding four tracks, two experiments and two standard works from Stetson, before leading us to the door of a long-form composition, a format he had great success with on the previous New Millennium Warfare record.

“The Lure of the Mine” proves to be the greatest piece of the album, offering both the most discreet development and the greatest amount of integrated influences. One can see reflected in its 12 minutes shades of his time in Arcade Fire and Bon Iver, their particular moodiness and progressions, can see the tension and sorrow of Gorecki, the spiritualism (because there is no jazz devoid of spiritualism) of his own New History Warfare series. It is placed last, perhaps, because it feels very much a culmination of this very disparate record and the scattered experiments preceding it. It offers an exciting springboard for Stetson in the coming years and stands as a validation of the experiments and side-projects pursued thus far. This feels very much like a transitional and recompositional record, a resettling of Stetson’s position and aim, and in that regard it situates him in an exciting way.

Similar Albums:

Colin Stetson and Sarah Neufeld – Never Were the Way She Was

Colin Stetson and Sarah Neufeld – Never Were the Way She Was

Matana Roberts – COIN COIN Chapter One

Matana Roberts – COIN COIN Chapter One

Julianna Barwick – Will

Julianna Barwick – Will

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.