Pick Your Poison: Jim O’Rourke’s Eureka vs. Insignificance

I first knew of Jim O’Rourke as a producer. The Chicago-born experimentalist and avant-garde overlord was cited as the reason Wilco were dropped from their label, Reprise, when they wrapped up the recording of their chef-d’œu·vre Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, which soon became a greatly lionized artifact of indie rock history. O’Rourke, a long time friend of Wilco frontman Jeff Tweedy, notoriously warned Tweedy that if he was indeed commissioned to produce Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, Wilco would be dropped from their label; that was the exact outcome, and after a strange attempt at releasing music digitally in the quondam days of the Internet, Yankee Hotel Foxtrot was picked up and re-released by Nonesuch Records.

Is it true that O’Rourke played a definitive role in the shaping of twenty-first century rock music? Yes. But O’Rourke’s name has been shabbily stuffed into the historical texts of the Internet-ruled landscape of contemporary music for far too long. Aside from O’Rourke’s tenures in Sonic Youth (1999-2005), Chicago art-rockers Gastr del Sol, and the eventual supergroup Loose Fur, alongside Tweedy and Wilco drummer Glenn Kotche, O’Rourke has released a sea of vivid, orchestral-pop and avant-garde music that has a loose “rock” backbone but often explores jazz, noise-rock, ambient, and American primitive territory. The latter was the end result of O’Rourke’s 1997 opus Bad Timing, a meandering, meditative, and lively collection of American primitive guitar artistry (an absolute and personal favorite of mine as well).

But what followed Bad Timing was entirely dissimilar: 1999’s Eureka and 2001’s Insignificance, two albums uniquely complex and layered with stunning chamber-pop and orchestral arrangements. O’Rourke’s trio of full length albums spanning from 1997 to 2001—Bad Timing in 1997; Eureka in 1999; Insignificance in 2001—draw significant influence from the late director Nicolas Roeg, whose films Eureka (1983), Insignificance (1985), and Bad Timing (1990) are the namesakes for the aforementioned O’Rourke albums. But the similarities don’t necessarily stop there—like Roeg’s films, which are dense, chronologically dispersed, and often borderline surrealistic, O’Rourke’s music lies within the same disposition, most notably Eureka and Insignificance.

Eureka is the “grower” of the two—upon initial release, it received mixed reviews, mildly overshadowed by both breakout albums and stellar midway releases from the indie rock aristocracy, such as Built to Spill, the White Stripes, Sleater-Kinney, Will Oldham, the Magnetic Fields, Pavement, Low, Blur—the list goes on. It’s reasonable to assume that the general direction “rock” music was headed in would leave O’Rourke out in a vulnerable space of obscurity. What the public consumers craved based on the previously mentioned albums was direct, pop-oriented albums. Eureka may not have been direct, but it was certainly pop-oriented—pop-oriented the way David Lynch’s Eraserhead is considered a horror film. Its characteristics resemble the structure of the term, but there is a vehement otherness to it.

Insignificance, though structurally similar to to its predecessor—scatterbrained and open-tuned guitar arrangements, symphonic, layered vocals—differs conceptually. Insignificance drops the brass and string-heavy instrumentation for a guitar-based approach, O’Rourke’s fluent instrument of choice. O’Rourke uses the methods of arranging, anatomizing, and dissecting sounds he mastered on Eureka and translates that to guitars—electric, acoustic, pedal steel—on Insignificance. This seems to be where O’Rourke feels most comfortable, or at least within this specific time frame. As compatible as both Eureka and Insignificance may be, though, they both share a unique attribute found in much of O’Rourke’s work—overwhelming befuddlement. To hear Jim O’Rourke for the first time is to exercise your brain, tease your ears, to feel as if you’re spinning out of control.

Reflecting on censorious assessments and first-impressions criticisms of Eureka nearly 20 years later, it’s bizarre and slightly perplexing why Eureka was so rigidly dismissed. A substantial portion of late aughts and early ‘10s indie rock extracted influence from O’Rourke’s methods of orchestrated chamber pop. Grizzly Bear, Fleet Foxes, Dirty Projectors, Arcade Fire, The Decemberists, The National—each absurdly acclaimed and respected groups of the past decade or so—pull from these same methods O’Rourke revitalized in the late ‘90s. Whether consciously or not, these artists were doing what O’Rourke did with Burt Bacharach and late-period Beach Boys records (Pet Sounds, Smiley Smile (or The Smile Sessions for the purists)), composing rock-oriented music with archaic methods, approaching the studio with a blueprint of a composition rather than a song or an album.

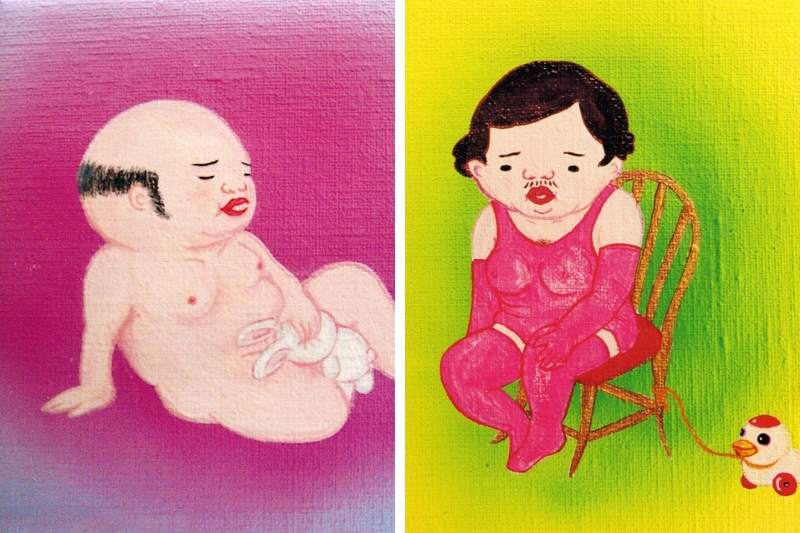

The pair of albums have aged gracefully since they were released, though both practically vaulted and hushed from the discussion of landmark “indie” records. Perhaps this is due to O’Rourke’s self-induced opacity as an expert experimentalist, ditching Chicago for New York and then New York for Tokyo. It’s also difficult to place any other release of O’Rourke’s under the same lens as Eureka and Insignificance, as they arrived in a thoroughly transitional period of rock-oriented music, and shared similar album art, courtesy of the very-much NSFW artist Mimiyo Tomozawa.

From the album art inwards, both Eureka and Insignificance share thematic similarities, and the manner of which they were composed are even more parallel. But the complex time-signatures that O’Rourke administers on his guitar on Insignificance are no match for the bubbly, grand arrangements splattered across Eureka—it also plays in O’Rourke’s favor that he borrowed two songs on Eureka, Ivor Cutler’s “Prelude to 110 or 220/Women of the World” and Burt Bacharach’s “Something Big.” Regardless of O’Rourke’s stature as an original songwriter on Insignificance, though, Eureka downright displays an artist that was certainly out of his mind and most certainly out of his time—only history will tell, but at this point, Eureka reigns supreme.