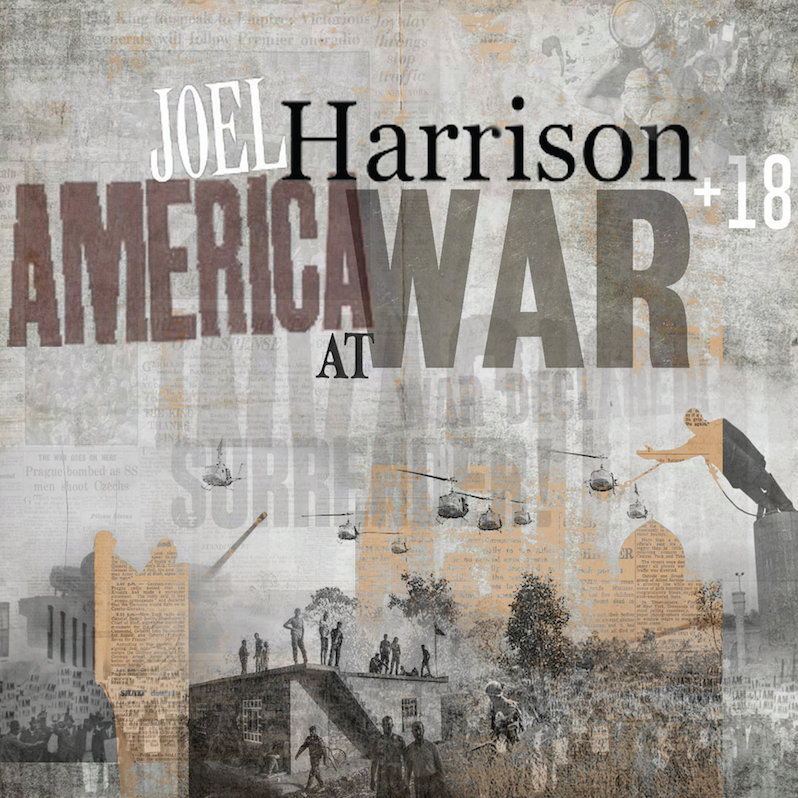

Joel Harrison +18 : America at War

I’ll cop to this: for the longest time, I was not a big band jazz fan. More than that, even. I was a hater, dyed-in-the-wool, sneering at what I considered cornball nonsense compared to the stark strands of Scandinavian jazz and the wild progressive sworls of fusion at its best. I mean, sure, I repped some smooth jazz records too, but if you couldn’t hear the difference between peak Yellowjackets (it’s Four Corners, by the way) and Glenn Miller grandma jazz, you were deaf.

Except, as it turns out, I have had to eat crow on this mark a staggering number of times, and Joel Harrison’s immaculate America At War is another glorious bite of birdflesh for me. For one thing, Harrison’s approach to big band arrangement sits decidedly in the post-Mingus Big Band milieu, preferring to have one or two soloists improvising more or less at all times, giving a sense of perpetual liveliness to the entire affair. What’s more, the basis of the jazz here is closer to the funk-rock exaltations of some of the tastiest Miles Davis fusion records (ensembles so large they’re functionally big band records in their own right), with a nasty-ass guitar tone married to an often stink-face inducing sense of syncopation, pocket and just plain groove. As a result, when the horns start doing that stacked third unison motions trick big bands love to employ to signal it’s big band jazz time, it feels more as a shocking and pleasant burst of convention in otherwise unconventional affair rather than eye-rolling tedium.

Harrison is also hip to the general movement over the past, gosh, 50 years or so to more orchestral arrangements in big band contexts, with some passages sounding or feeling almost more like soundtrack music. The great beauty of America At War is that the precise vibe of the implied films of these soundtracks shifts moment to moment, track to track: here, a sexy spy thriller, all PP9s and fluttering ties against ’70s suits in browns and blues and reds; there, a drugged out psychedelic anti-war odyssey. One second, the electric guitar busts out a heavily effected tone, like Hendrix jamming over Brötzmann, and in the next a clean folksy pluck. The horn players too are exceptionally adept at shifting their tone at the drop of a hat, even mid-piece, having on one end the necessary sass and stank that jazz-funk calls for before switching to the breathier and purer tones an orchestra might deploy for tricksier, more sensitive passages. The keys player deserves a shout out, too; one moment, he’s laying down spectral synths like peak Hancock and the next punching in a charming bebop groove. The entire affair bleeds charisma from every corner, reminding in only a few seconds why a modern heavyweight like Kamasi Washington prefers this mode of jazz in the first place and why recontextualizations of the canon like the Mingus Big Band made such a major splash in the world of big band arranging in the first place.

And this is all without mentioning the conceptual arch to the record, which is one of deep anti-war politics, focusing on America’s structural tendency to war and who tends to suffer most. The funk in particular seems to invoke specifically the extraordinary punishment that people of color in America past, present and (horrifically) future bear with our war-like tendencies. The first track, “March On Washington,” certainly is intended to evoke the anti-Vietnam protests but its impossible with a title like that not to think of the march on Washington during the civil rights movement, a sentiment echoed in the final track “Stupid, Pointless, Heartless Drug Wars.” Placed alongside tracks like “My Father In Nagasaki,” a clear nod to anti-nuclear sentiments even in the case of World War 2 (a sentiment sadly, frustratingly uncommon even still!), as well as “Yellowcake,” a reference to uranium used for bombs, and “The Vultures of Afghanistan” bringing up the modern apocalyptically devastating wars of George W. Bush, you get a good sense of the totality of Harrison’s argument. These objects are all linked in his mind and on this record, with the abuses of black people in America being inextricably tied to our comfort bringing nuclear holocaust onto Japanese people and our psychopathic decade-plus abuse of the people of the Middle East that has now spanned three presidents of three quite different political molds, topped off with our racist and classist human meatmill in the form of the war on drugs.

But he is very clear to not condemn the entirety of the soldiering class. There is one vocal song on the whole record, “Day After Tomorrow”, and even then it is buried close to the end, preferring to let his programmatic orchestral flourishes and intensely musically sensitive large ensemble carry the weight of the images, narrative, and politics of the record. This vocal piece is from the perspective of a young soldier, on the verge of 21, who quickly grows disenchanted with the act of warring after seeing it firsthand, grappling with the fact that his country lied to him and stoked a psychopathic patriotic fire to get him to go and kill other kids his age in its name. The figure doesn’t believe in war anymore, doesn’t believe in what he’s forced to do; he only fights to get home, to see his family, and to make sure it never happens to anyone else ever again. This is a powerful and unifying sentiment, one that acknowledges we cannot both carry out righteous fury against the imperial capitalist death machine and state its propagandistic wing and then turn around and blame people for falling for the lies it tells. What matters to Harrison and to this record is that people wake up and, having done so, stand in solidarity with one another against these wickednesses.

Not bad for a jazz record. Hell, if anything, being this bold about politics in the world of jazz puts him in the company of some of the best to ever do it. We forget sometimes that one of the worst crimes in the gradual whitening and class-traitorism jazz was forced to undergo was its slow divorce from radical politics, where the radical blackness of even a figure as late as mid-period Herbie Hancock and Miles Davis would less than a decade later be seen as grotesque and self-indulgent. The aforementioned Brötzmann’s critical breakthrough work was a suite aimed squarely at the Vietnam war, expanding Hendrix’s vitriolic take on the national anthem into a serenade of machine gun fire in the perpetual spiritual terror of the jungle in wartime. America At War wants to live in those same spaces and, in my view, succeeds. Its tendency toward more approachable melodies and rhythmic figures and timbres is to its benefit; I can’t imagine any serious lover of music, whether jazz or not, turning their nose up at this record. Its perpetual tunefulness and endlessly inventive imagistic programmatic flourishes are too arresting, too compelling, to even think of saying no. I’ve got to stop doubting big band jazz, man.

Label: Sunnyside

Year: 2020

Similar Albums:

Kamasi Washington – Heaven and Earth

Kamasi Washington – Heaven and Earth

Sun Ra – The Magic City

Sun Ra – The Magic City

Charles Mingus – Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus

Charles Mingus – Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.