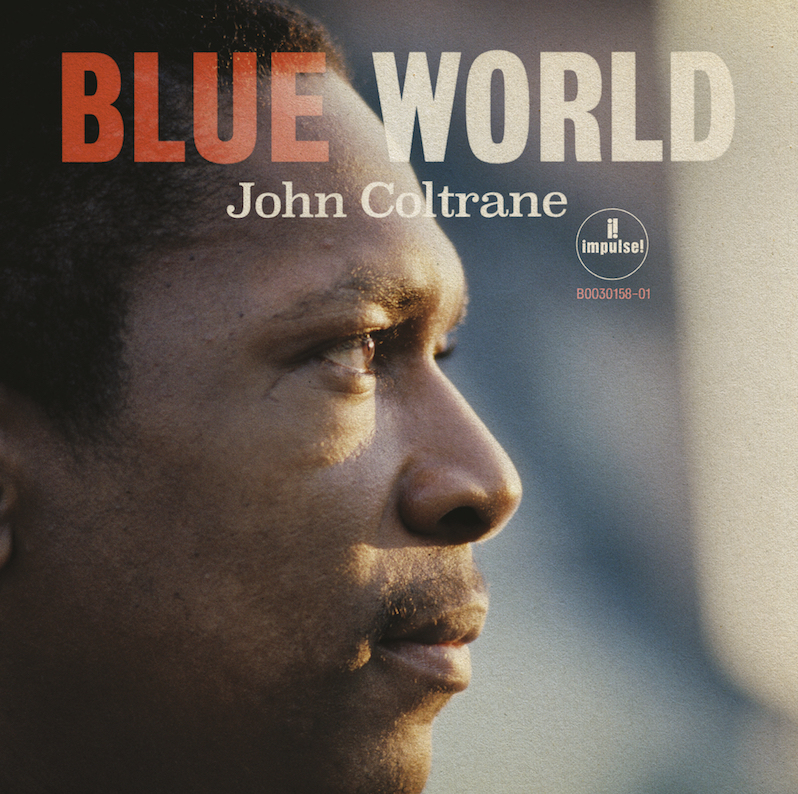

John Coltrane : Blue World

How good do you have to be for a flawless hard bop record to be an inessential contribution to your legacy? Simple: You have to be John Coltrane. On paper, an unheard record by Coltrane’s classic quartet, comprising bass player Jimmy Garrison, drummer Elvin Jones and pianist McCoy Tyner, all legends on their instruments, is a saliva-inducing proposition. After all, this is the greatest bop combo in history we’re talking about; there may be better individual players in figures like Charlie Parker and Bill Evans, but as a unit, this is the undisputed cream of the crop. Combine this with the fact that this record was cut in 1964, wedged right between the sessions for oft-overlooked avant-bop record Crescent and A Love Supreme, one of the greatest pieces of music humanity has authored thus far, and it should be hands-down one of the most desirable pieces of archived music emerging from the vaults we’ve possibly ever seen.

And what’s wild is the album is exactly as good as that sounds. Blue World, over its eight tracks, covers these four players at their best both personal and group best, delivering solos and comps that are virtuosic while still making clear room for other players, showing masterful technique not just in speed or precision but also control of timbre and the subtler elements of sound. The opening bass solo on the rendition of “Traneing In” here is a recording of such high caliber you will swear there’s a misprint, that this simply couldn’t have been recorded 55 years ago. How could a bass sound this good from that far in the past, have a recording that makes you able to palpably feel Garrison’s fingers scrape against the thick strings of the double bass? Both renditions of “Naima” featured here underscore why the piece is widely considered Coltrane’s greatest ballad and why, even decades later, the only way to really play the piece right is do so wildly different from the classic quartet who made it their own. There’s just no beating them at their own game.

So then why does the record add little to the legacy of this group? Well, for one thing, it’s a legacy already well-earned by other recordings, such as the aforementioned A Love Supreme, the jaw-dropping Impressions and even last year’s acclaimed lost album, Both Directions At Once. The classic quartet period of Coltrane’s body of work, despite producing less than a dozen albums in its half-decade of life (a snail’s pace for jazz at the time), is a widely accepted master group producing the finest combination of bebop, hard bop, post-bop and avant-garde jazz that early 60s could provide. So to add another record to the pile, even a masterful one that plays a fine sibling to its accomplished compatriots, effectively adds very little to our understanding and respect of this era for the players involved. Add on top of this that John Coltrane is already one of the most celebrated musicians of the 20th century period, the inestimable esteem of Elvin Jones and the jazz legend status of both McCoy Tyner and Jimmy Garrison (Garrison being the most overlooked of the four) and another record does little to move the needle. This isn’t Blue World‘s fault, mind you; it would take not just a great album of flawless jazz but a genius and visionary record lurking in the vaults to majorly shift our already great appreciation for this period.

It doesn’t help things, of course, that Blue World only features a single original composition across its eight tracks and that three of the remaining seven are alternate takes. That comes out to five pieces in a set of eight, already not a great ratio, and most of them being new takes on tracks that we already have plenty of quality performances on hand. “Naima” is a brilliant song and “Like Sonny” is an overlooked and fine set of chords, but it’s not really necessary to give us more if the solos and comping are going to stay inside the lines this much, and absolutely no one was clamoring for three separate but near-identical takes of “Village Blues” to crowd the same album. The solos and approaches shown here stick to the relatively conservative approach of Coltrane’s classic quartet, displaying that he and his bandmates knew full well how to lay down bebop right, a decision made to bugger off critics who accused them of being as free and avant-garde as they had been more because of drugs and lack of discipline than artistic vision. But these capabilities to play it straight and make it mean something are likewise already well established on other records, making the contributions of Blue World unnecessary.

The album wins back esteem on the back of its title track, a stunning and subtle composition with some top-notch solos from the players, as well as the fact that the whole thing was originally recorded as a soundtrack for a French drama. The director contacted Coltrane asking for music and, due both to director request and a time crunch, the group mostly sent recordings of existing pieces with only a single new song they’d been working on at the time, accounting for the larger-than-normal number of retread tracks, the relative safety of the approaches to solos and the number of alternate takes. The director, either the bravest or dumbest man on earth, decided to scrap his Coltrane classic quartet original soundtrack for, God, who knows, something definitely worse, and thus left this in the vault. The estate and label were right to wait on this until after Both Directions At Once; of the two, a full shelved album of largely original material definitely contributed to our understanding of this period and appreciation of its players much more than Blue World could or does.

But if anything the fact that a set of pieces this startlingly beautiful, this profoundly elegant, and this perfectly full embodiments of their genre could sit in a vault for decades and on release offer little new to say about the group is the testament to the group’s power. Blue World becomes fascinating precisely because this set of recordings is only ho-hum in the context of the greatest bop combo of all time; any other player regardless of genre would kill to have a record this gorgeous in their discography, let alone mouldering in a vault somewhere. To those who are well-acquainted with the body of work of this group and its constituent players, Blue World offers little save another treasured glimpse at a period of Coltrane’s work ironically finally becoming overshadowed by his more adventurous (and better) later period, while to newcomers it offers insight on why this lineup has the esteem it does inside the jazz world. And at the end of the day, who cares if it contributes little to furthering our appreciation of this period? The songs are beautiful.

Similar Albums:

John Coltrane – Both Directions at Once

John Coltrane – Both Directions at Once

Kamasi Washington – Harmony of Difference

Kamasi Washington – Harmony of Difference

Miles Davis – Round About Midnight

Miles Davis – Round About Midnight

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.