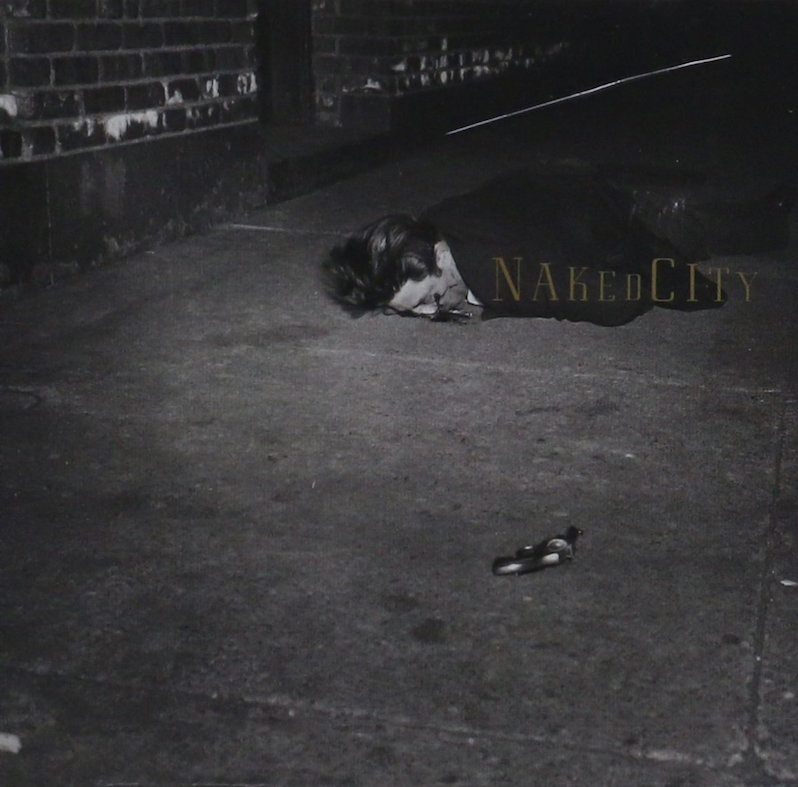

John Zorn’s Naked City was a gleeful noise-jazz science experiment

Here is a list of things Naked City sounds like: a jazz “Revolution 9,” a broken tape of a French murder mystery, a rollercoaster on the brink of falling apart, the varsity jazz band in a mental institution, The Wizard of Gore, a man in a red velvet suit whispering something seductive and then screaming in your ear, nothing else.

Naked City is free jazz, at least some of the time. Free jazz didn’t just expand on the premise of jazz, it blew it to pieces, usually with the power of a lot of breath blown into a tiny reed. The free jazz Naked City is most indebted to is Albert Ayler, who was playing blast beats before black metal was even a nascent dream. Zorn has discussed the influence of Ayler, along with Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor: “There is a clear connection between the energy music of the ’60s and hardcore punk in terms of energy, sound and tension.”

John Zorn made this connection explicit on his 1989 record Spy vs. Spy, a collection of Ornette Coleman covers played with the intensity of hardcore. And on 1990’s Naked City, Zorn goes a step farther, joining the intricate intensity of free jazz with the visceral violence of grindcore. Zorn acknowledged this molding of what was perceived as both high and low art, saying “all these things are the same and there’s no hierarchy in music.” Maybe Zorn was lucky no one before him thought to bring these complementary genres together, but Naked City isn’t great just because of the novelty, it’s great because Zorn’s conceptual vision is both rich and surprising, folding in lounge and dark ambient among other genres.

What doesn’t get talked about enough is how funny Naked City is. It’s like that kid in elementary school who had to sit on his hands because he was distracting everyone. Only that kid got a saxophone and a stage. There’s a silliness to the album; its combination of jazzgrind with movie themes and surf rock, while eliding ironic or cruel jokes, finds humor in agility, moving between these genres without reason or warning.

This structure is executed with brilliance. The record begins and ends with its most “normal” tracks, with the harshest songs coming in a suite of noise-jazz in the middle. This section of the record sounds like we’re trapped in a noir on ketamine, listening to the world’s freakiest house band. This is a world of shadows and intrigue, car chases and shootouts, kooky gadgets and vintage vehicles. During the 1970s, Zorn was part of the film scene in New York, and the influence of scores is apparent here. The movie themes covered in Naked City fill out the universe. Batman, I Want To Live, Chinatown: both famous and obscure movies are played straight, with grind and avant embellishments, but never to poke fun. Zorn is an avowed lover of film noir, especially its “mood,” and stylish cynicism is the prevailing mood. Within the dream logic of Naked City, the theme to “The Sicilian Clan” makes total sense next to the psychotic “You Will Be Shot.”

On the latter track, Zorn squeezes a shrieking squelch out of his saxophone, but what’s more impressive is how he can then turn around and be as big-band-raucous as he is on “Latin Quarter.” He has an ear for a well-timed melody as much as a well placed skronk. John Zorn plays his saxophone like he’s trying to reanimate a corpse with it. At times, he wills the body to dance, at others to lounge, and at his most violent, he screams and screams and screams at it to wake up. Zorn says that for the first 15 years he played saxophone, he played Ornette Coleman songs, and there’s a distinctly Colemanian versatility and deftness with which he moves between violence and melodicism.

The other most notable player on Naked City is Boredoms’ vocalist Yamatsuka Eye, who mostly does his thing on the album. But, of course, Eye’s “thing” is some of the most beguiling vocal work ever recorded, and Eye is in peak form here. There’s some hardcore punk in Eye’s performance, but also scatting, babytalk, “Whazzzup,” the demons in The Evil Dead, blowing 100 loogies per second, and a machine gun.

But John Zorn’s Naked City is also strengthened by two unsung players: Joey Baron on drums and Bill Frisell on guitar. Baron is having an absolute ball, like on “Batman,” when he tumbles across his set like they’ve been thrown down the stairs, and Frisell often carries these songs while Zorn takes his saxophone through the gates of hell. They create a tension between melody and noise, something the band and album as wholes play with throughout Naked City. Since the ’70s, Zorn was forming groups of disparate musicians to improvise. On Naked City, John Zorn and his oddball group found the pulse of something entirely new.

Zorn’s greatest talent is his understanding of when to fuck shit up and when to step back. A song like “Punk China Doll,” one of the best on the record, represents this. The first few seconds sound one down-tuned guitar from black metal, but then they switch to math rock, then to pure experimentalism, bolstered by a ripped fabric guitar solo, and then finally a bit of primitivist, dark ambient peace. This is a song that breathes, full of built-up pressure and then glorious release. The whole record follows this coke-and-mentos mentality, a gleeful science experiment performed by one of modern jazz’s most restless creators.

The reputation of Naked City positions it as an all encompassing monster, eating every genre in its path, chewing these up and spitting them out, leaving free jazz saliva covered bits in its wake. And it is little bit; the first listen can feel like watching a horror movie played backwards. But Zorn’s intent is always to overwhelm, and never to exhaust. His genre hopping always follows a method, even if his meaning isn’t clear to us. This soup, this everything-and-the-kitchen-sink approach, makes sense precisely because it makes no sense at all.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.