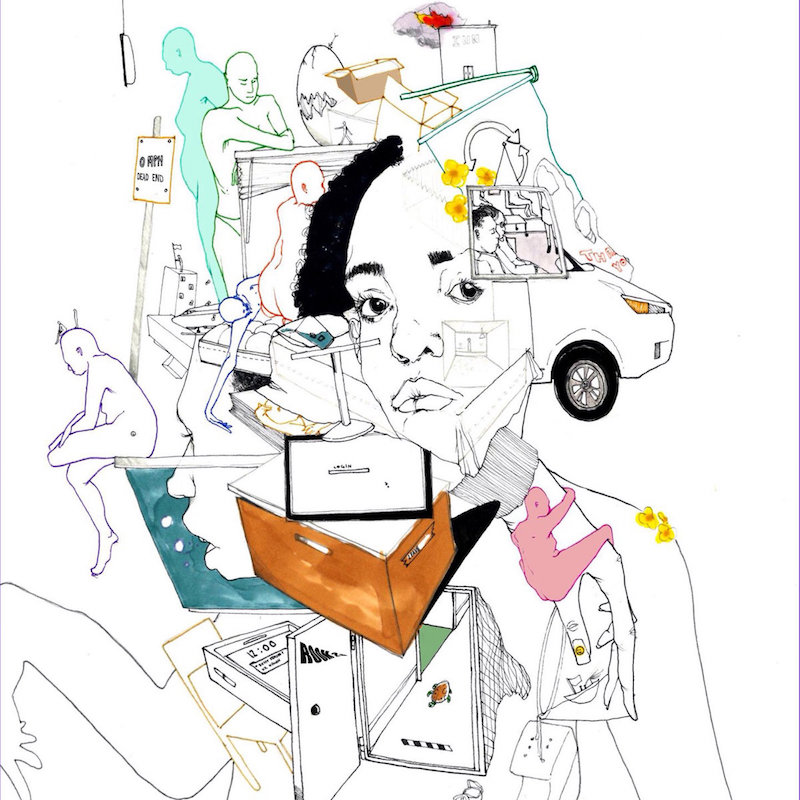

Noname : Room 25

During her excellent NPR Tiny Desk concert, Chicago rapper Noname describes her general writing style as “scramble-think,” but saying that is a disservice to her work. Noname’s lyrics are willfully impressionistic. She veers between clear, representative statements and clusters of loaded images; she works to show the listener both the truth of the matter and her reaction to it. On the second verse of “Blaxploitation,” the second track on her debut album Room 25, she constructs a pointillist critique of the commodification of Blackness by stacking vignettes on top of one another; she jumps from a young man contributing to neighborhood gentrification to a Black maid cleaning his house to her own staticky recollections of Pine-Sol ads to the hypersexuality of BET Uncut re-runs to Hillary Clinton flaunting her hot sauce for authenticity points on The Breakfast Club. What she calls a “scramble” comes from an effort to address everything—it really is all about associations and interconnectedness, about how information comes from all angles and collapses upon itself. She’s painting a portrait of her own complicated, deeply busy mind; she’s asserting and negotiating a sense of interiority and selfhood for her distinctly Black American experience.

What’s so powerful about Room 25 is the way Noname juxtaposes her hard-won sense of self-worth with her moments of doubt, as on the wrenching immediate highlight “Don’t Forget About Me.” Longtime collaborator and multi-instrumentalist Phoelix (who produced the entirety of the record) provides his slow, aquatic funk, Matt Jones arranges a wave of sweeping Technicolor strings, and Noname talks about a fan letter she received that told her that her 2016 mixtape Telefone “saves lives.” But she knows that the healing her fan is talking about doesn’t extend to her: “The secret is I’m actually broken,” she says, that she “almost passed out drinking” because she thinks that “saves lives.” She’s working hard to contend with the impact of her heart and understand how she can help others without being whole. She expresses this with crushing, religious humility on the hook of the song—even if her art “saves lives,” she’s focused on family, on the people she knows and loves: “I know my body’s fragile, know it’s made from clay / But if I have to go … I pray my momma don’t forget about me.” It’s both brutal and comforting, an acknowledgment of mortality and a testament to familial love.

All through the record, Noname tries to work through her imperfections without being held back by them. She’s introspective in a near-therapeutic sense, trying to confront her issues in real time. This is especially true to her love songs, and Room 25 is a “love” album (think Beyoncé’s 4) in its way. “Window,” with its swooning orchestration and clean electric guitars, finds her both thrilled and melancholic in temporary, headstrong love, seeking connection even when she knows her man can’t love her back: “I know you never loved me but I fucked you anyway … I loved you even though we’re not meant to be.” Elsewhere, she comes to terms with and finds comfort in her sexuality; she finds peace in her loneliness, and ecstasy in love. “Montego Bae” is an absolutely unabashed love song, open in its affection. Over an appropriately flirting-with-calypso backing, Noname catalogues a to-do list for her new love: reading old books with new eyes, “sucking dick in her new Adidas,” learning how her man like his curry (“spicy,” FYI). Her love songs see love as fulfillment and encourage empathy even when love is unfair; she ends “Window” telling her doomed love, “Everything is everything / Just know that I love you.”

You could say that Room 25 is a personal album, but not in the traditional sense of “personal” where the word connotes oversharing or naked sentimentalism or whatever. Room 25 is personal because it’s an expression of personhood, a project only Noname could write and rap and assemble. She moves fluidly between personas and topics, equally capable of embodying and addressing each. The frantic “Prayer Song” sets sex and violence and gentrification equal to each other as expressions of the same impulse toward power; and “Ace,” with Smino and Saba, is just a pure flex, three friends talking their shit, trading slippery polysyllabic flows and trying to one-up each other. It’s fitting that the project ends with a song called “No Name,” but, equally fittingly, the song is as much about who Noname is as who she isn’t. She closes her sophomore album explaining that being Noname means she has “no name for people to call small or colonize optimism”; that “when labels ask [her] to sign [she says her] name don’t exist.” She is what she isn’t; she is what others aren’t, and what others can’t have. “Only possession I have is life,” she raps. And it’s true. All any of us have is our lives. But Noname’s is hers.

Similar Albums:

Chance the Rapper – Coloring Book

Chance the Rapper – Coloring Book

Jean Grae and Quelle Chris – Everything’s Fine

Jean Grae and Quelle Chris – Everything’s Fine

Frank Ocean – Blonde

Frank Ocean – Blonde