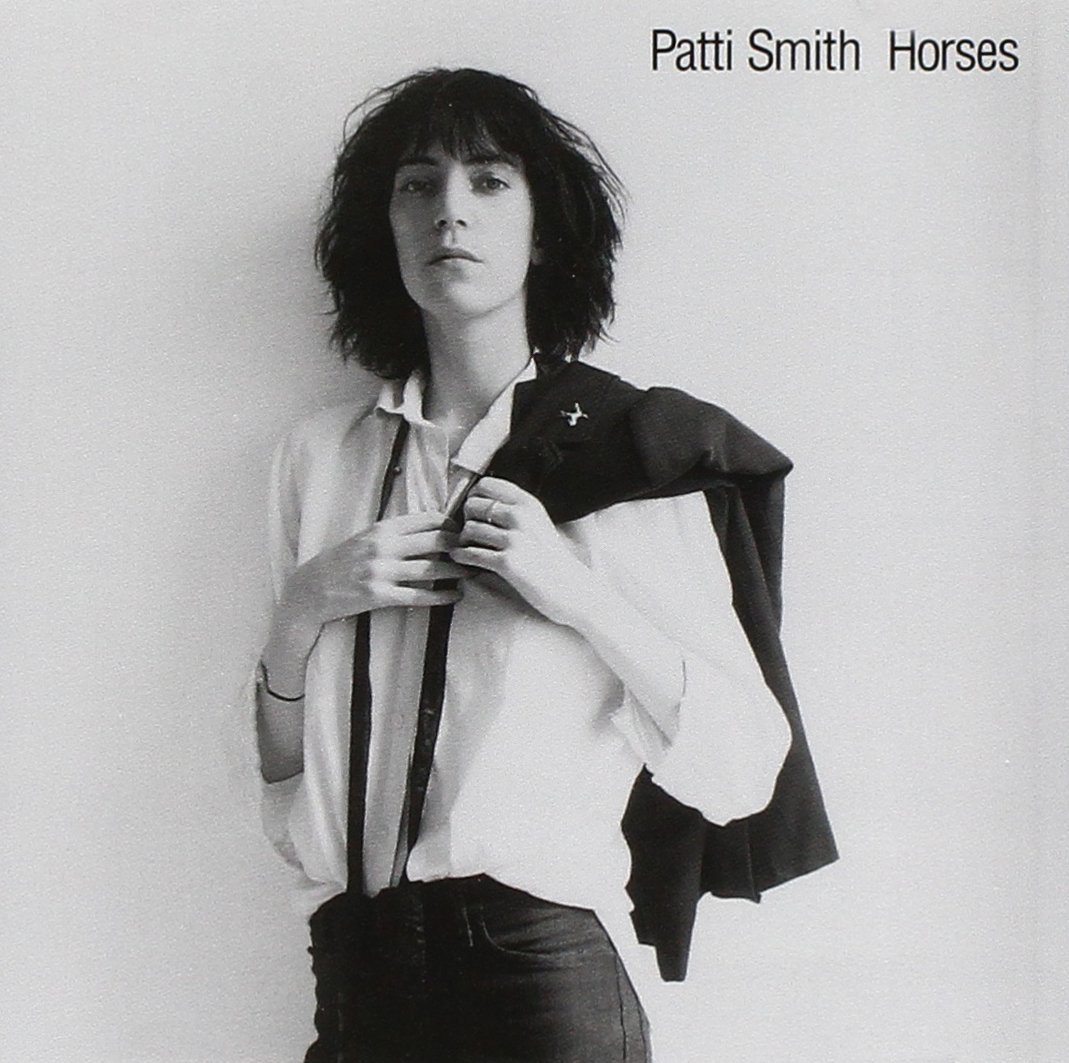

Patti Smith : Horses

So, you’re introduced to someone, a woman, and your first impressions of her are taken from an iconic photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe in which she is flashing all the androgynous sexuality that has been seething in the corroded corners of your erect little mind. She hasn’t said word one and already you feel your throat drying out, observe yourself as you begin unconsciously slipping your hands in and out of one another, kneading them because, man, your nerves have popped out of your skin and are rubbed raw by this presence, this spectral vision of woman which has unexpectedly disordered the pristinely mundane abstraction that you call your life. You can’t really move too much besides the whole embarrassing fondling of your own hands, you certainly cannot speak and then, when she finally does speak, what she says draws you down into an intensity of thought, feeling, emotion, that you had begun to think of as an happy fiction. Luckily she pauses for a moment and you have time to observe the aberrations in your psychical and physical being, however superficially.

“Jesus died for someone’s sins, but not mine.” Mine neither, mine neither sister; and suddenly you are in the middle of a song, she is singing, her voice an immaculate cradle of filth, curdling into a skanky, somehow continental, strut and you are standing in the middle of this song hand in hand with yourself, eyes dilated, perspiration dripping down your cheeks and this, this is rock and roll. This band is playing rock and roll, stripped, nothing novel about it rock and roll—what you had imagined rock and roll to be but never quite heard.

And this girl, this woman, this ethereal entity is slithering into your ears and eyes, dangling from your neck and you can’t breathe; the music is kicking in harder and harder, a million bumblebees are bursting in your blood and blowing out your veins.

G-L-O-R-I-A

“Wasn’t this a Them song?” you think, but this is not the same song—it is something altogether different, different from Jim Morrison’s mutation, different from anything you have heard. She is talking about a she, Patti is, a she humping on a parking meter, a she that is saving her from the boredom of a pallid little party, just about the same way the song is shaking us free—a she that transfigures the world. Song ends. What the hell just happened?

Patti Smith. And about the time “Birdland” starts climbing up the walls, stretching out to a jaw dropping shape and magnitude, you have a moment of lucidity; it’s not what she is saying, but how she is saying it. The words in themselves are interesting enough, but the way she expels them, vomits them out into the world, mad, delighted in squalor, seething out of the margins of consciousness and society—that is the safety-pinned-together heart of rock ‘n’ roll. Going up, bye bye bye bye… This is beauty, back end of the 20th century beauty, the pathological incantations of a hyper-intelligent disposition making itself material, transposing itself on what has come to pass for reality, for experience. How many times does one really come face to face with beauty, beauty in an expansive and relentlessly affecting sense? Like Bill Blake says, “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is: infinite.” And this is some door cleansing medicine and yes, that is where The Doors got their name, and no, it is not a coincidence; Jim Morrison was after the same thing as Patti: rock and roll as derangement of the senses, as inducer of visions. The distortion of reality is viewed here as part of rebirth, as a necessary process which will inform a conception of a greater, more vital reality.

There are songs on Horses that one could describe as pretty, as beautiful in a more tangible, more pejorative sense. “Free Money” and “Break it Up” are good examples. But the beauty in these songs escapes the easy trappings of gelatinous sentiment. If only I had money my love and I would run away, live in the netherworld, in a paradise loosed from the strata of society. A familiar enough notion, but rarely does it seem so natural, so sincere as when Patti voices it, gives it an aura of absolute desperation, makes of it a cacophony of dollar bills swirling around your head, spinning unto nausea. “Break it Up” includes Tom Verlaine’s guitar doing the electric bird boogie, screeching, wobbling, giving the song and it’s inflated chorus a counterpoint anxiety to go along with that inflected by Patti’s voice. But where we get back to the heart of the album, is in “Land,” her unaccompanied voice relating some story about some Johnny banging his head against some locker and suddenly Johnny is seeing horses, all kinds of horses really, pulsing around in his head and then in your head and then this strange hallucination of horses collapses into a simple guitar riff and Patti exploding on and on about dances like the mashed potato and the alligator and the twist, and this is about one thing, which she makes perfectly clear: Gotta Lose Control. Dance and have your mind blown in the same song. Go Rimbaud. Je est un autre. I used to listen to this shit and read Rimbaud a lot kids, and I was pretty happy.

Similar Albums/Albums Influenced: John Cale – Fear

John Cale – Fear PJ Harvey – Dry

PJ Harvey – Dry Iggy Pop – The Idiot

Iggy Pop – The Idiot