It is the late ’90s in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and Britpop lies sullenly in a corner, battered, bruised and wheezing. Despite, in its halcyon days, seeming to enjoy the unified support of an entire nation, it had since been decisively outflanked; on the one side by the likes of Radiohead, whose dark, droning warnings of dystopian apathy were beginning to make Britpop’s sunny optimism look like boneheaded delusion, and on the other by the feel-good girl power explosion pioneered by the Spice Girls, which had made much of male-dominated Britpop’s black-eyed braggadocio seem desperately uncool. The once-mighty genre—nay, cultural movement—had lost its footing, and was tumbling helplessly into self-parodical irreverence and obscurity.

After Britpop’s fall, the biggest names in guitar music were largely American. The Strokes, who filled Britpop’s cultural vacancy in 2001 with Is This It (and set down rock’s blueprint for the next decade or so in the process), hail from New York. Meanwhile, punk was entering its most commercially pliable incarnation yet, boasting artists like Good Charlotte and Avril Lavigne (who is, in fact, Canadian, though to most Brits, the distinction was moot). Many British acts that came to the fore in this period, like Busted or McFly, were so heavily influenced by their transatlantic cousins as to be essentially indistinguishable. Even foundational indie groups like Franz Ferdinand or Bloc Party, who released their debuts to rave reviews in 2004 and 2005 respectively, were hard to see as much more than various permutations on The Strokes’ new formula. It was only really The Libertines (who ended up burning out pretty quickly, courtesy of duelling frontmen Carl Barât and Pete Doherty) who were regarded as a potential British rival to the new Strokes-fuelled zeitgeist, and it is telling that one of their main lyrical preoccupations was a hankering for a former (albeit heavily romanticised) vision of England. “There’s fewer more distressing sights than that / Of an Englishman in a baseball cap,” insisted Doherty on “Time For Heroes.”

Musical output is something that us Brits take pretty bloody seriously. Generational memories of the British Invasion refuse to fade, and there is surely some kind of latent envy that, as America holds the cultural monopoly on so much else, our own undefeated niche in the world of music is to be clung to till we’re white in the knuckles. And if, like me, you’re of a more politically progressive persuasion, you might find that Britain’s musical roster is one of the few exports for which you can feel a smidge of genuine patriotism (David Bowie, PJ Harvey, and Harry Styles all warm the heart more than, for instance, the transatlantic slave trade). So it’s no surprise that our domestic music scene was rocketed into a period of near-manic intensity in 2006, when an album came along that reasserted British influence after a period of absence, bringing irony, wit, and cynicism in spades.

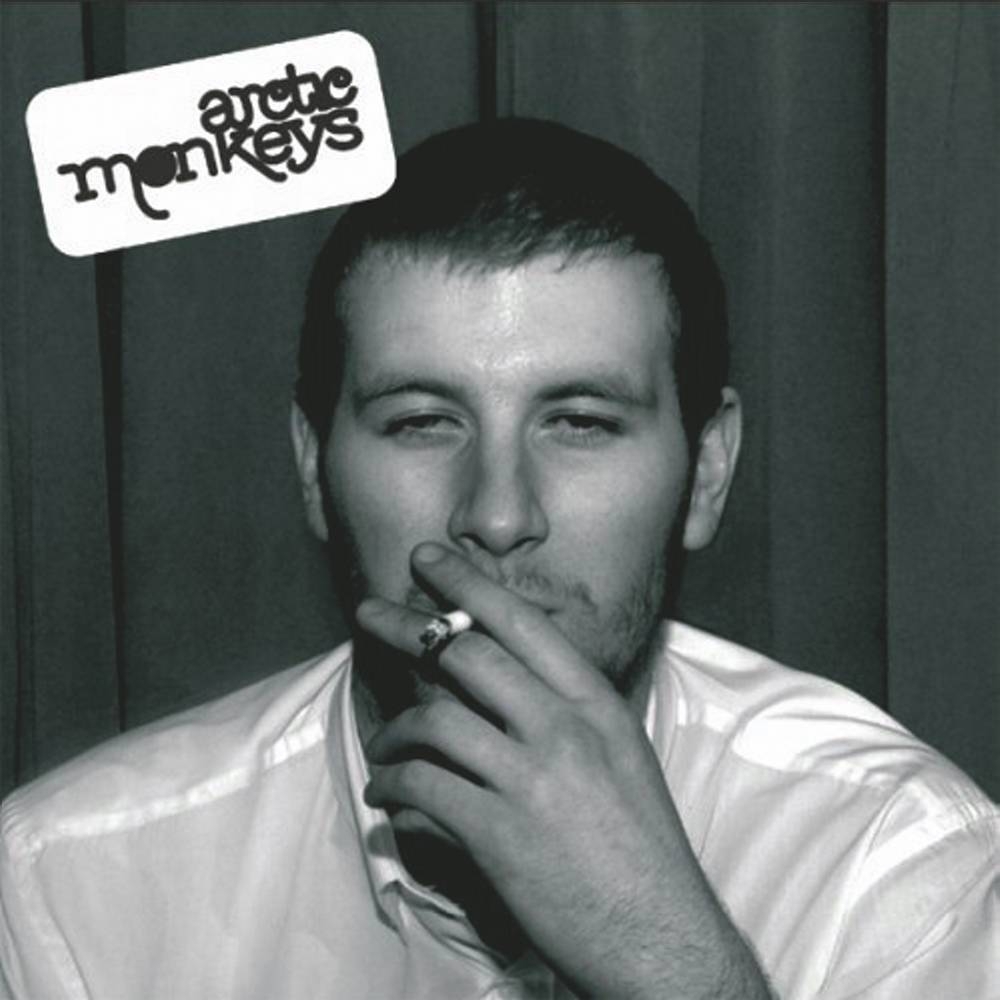

“Anticipation has the habit to set you up for disappointment,” warns Alex Turner, the Arctic Monkeys‘ charismatic frontman, in the very first lines of their debut release, Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not. It showcased a remarkably British perspective—wryly puncturing any seeds of optimism so we can all go back to being miserable—that kicked off the first song and continued for the remainder of the album.

Peppered with local slang and pop-culture references, Whatever People Say I Am made plenty of British listeners feel that the band were truly, honestly, coming from the same place as them (quite literally for anyone from the band’s home city of Sheffield—a few nearby towns and neighbourhoods, such as Hillsborough and Rotherham, are name-checked throughout the album). Turner panics on “You Probably Couldn’t See For The Lights But You Were Staring Straight At Me” that his situation is “So tense, never tenser / Could all go a bit Frank Spencer,” a nod to the exceptionally accident-prone Frank Spencer, protagonist of classic BBC sitcom Some Mothers Do ‘Ave ‘Em. Meanwhile, one of the record’s most enduring songs, “Mardy Bum,” takes its name from a North-English term for someone in a right old mood.

But that quintessentially English attitude extended far beyond a few easy catchphrases; it was embedded within the instrumentation itself. Though the Arctic Monkeys had clearly been influenced by The Strokes, Whatever People Say I Am certainly sounded much rougher than Is This It and its myriad offshoots; rawer, bouncier, with punchy, jagged basslines and fuzzy, pummelling riffs that carried strong hints of something you might reasonably call punk. Songs like “Last Nite” or “Someday” feel tame and delicate in comparison to tunes like “When The Sun Goes Down,” whose rapid, darting guitar and bass fills feel like a perfect mirror to the sweaty, flailing limbs of a drunken club attendee. And this was another sign of the album’s genius, for it was a perfect example of content meeting form.

The album is the story of a night out—any night out, every night out. We begin on the precipice of the late afternoon (“The View From the Afternoon”), where the narrator details his hopes for the oncoming night of debauchery. Though some fantasies are ambitious (“Girls hung out the window of the limousine”), others are rather more pedestrian: “I wanna see you take the jackpot out the fruit machine / And put it all back in!” Far from mocking this as trivial, though, Turner was reflecting with charming honesty the reality of how ordinary young men might seek to get their kicks at the pub on a Friday. The song is but one of many instances of such insight throughout the album, whose writing—given Turner’s age of barely twenty when the Whatever People Say I Am was released—we can safely assume to be method.

We move on through the night to drunken altercations in “Red Light Indicates Doors Are Secured” (“Two lads, squaring up, proper shouting / About who were next in the queue / The kind of thing that would seem so silly, but not when they’ve both had a few”), and then to dancefloor flirtations—not just with the acclaimed single “I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor,” but with the lesser known “Dancing Shoes”; “The only reason that you came / So what you scared for?” We eventually find the narrator being turned away from a club by a bellicose bouncer in “From The Ritz To The Rubble,” (“Last night these two bouncers / One of them’s alright, one of them’s the scary one / His way or no way, totalitarian!”), whereupon he resolves to wander off and get high instead (“Last night, what we talked about made so much sense / But now the haze is descending, it don’t make no sense anymore”). It’s the story of a night of adolescent misadventure, painfully relatable to any man who’s started their evening trying to emulate James Bond, but through a series of awkward mishaps and an over-indulgence in alcohol, eventually finding themselves as Jay from The Inbetweeners instead. Our protagonists stumble through fits and starts of cocky bravado hampered by whimpering, inebriated misjudgements, interspersed by a few snapshots of everyday life—relationships in “Mardy Bum,” callous cops in “Riot Van,” terrible first dates in “Fake Tales of San Francisco,” and the music industry itself in “Perhaps Vampires Is A Bit Strong But…”

The casual, knowing nature of the storytelling feels very modern, which is fitting for one of the first bands to make their name through the internet, via fanmade MySpace pages that shared tracks burned from free CDs given out at gigs. And, if it feels questionable to invoke modernity via hopelessly outdated social media and music formats, let’s not forget that even today, any nightclub boasting even the laziest dalliance with rock music will undoubtedly have “I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor” on its playlist. Indeed, 2016—a full decade after Whatever People Say I Am was released—was the year I started university, and the album was as popular then as it ever was, with its various hits being routine staples at any drinks preceding a night out on the town. The habit of me and a friend of mine to drop whatever we were doing when “From The Ritz To The Rubble” came on, and attempt to loudly sing along to the sort-of rap bit at the beginning, was no doubt embarrassing and uncomfortable for everyone else in the vicinity, and the Arctic Monkeys’ talents have ensured there is no doubt such scenes will continue to befall young revelers for generations to come.

The album remains relevant because, more than anything else—musically and lyrically—it’s truthful. It’s messy, it’s desperate, it’s lustful, and it’s obnoxious, yet it’s all this without appearing smug or condemnatory, because Turner knows that he is very much a part of the exact same alcohol-infused shambles that he’s rolling his eyes at. “I thought one-thousand, hundred things that I could never think this morning,” he admits in “From The Ritz To The Rubble,” the song that best frames the absurdity of the album’s message; from the hours of Saturday night to Sunday morning, you’re not just going out on the piss with your mates—you’re a different person in a different world. Whatever People Say I Am’s great achievement is to drag that world away from the inebriated haze of the dancefloor and into the cruel light of day, with just enough of a wink and a smirk to ensure that, in all its clueless, youthful idiocy, the grand tradition of the night out is ultimately being celebrated—and not (just) mocked.

Note: When you buy something through our affiliate links, Treble receives a commission. All albums we cover are chosen by our editors and contributors.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.