Hall of Fame: Little Brother – The Minstrel Show

“How would you like to come and work for me?”

“Yes, Ma’am! How much you gon’ pay me, I’s hope?”

“Well, let’s see now…I’ll pay you all that you’re worth”

“Nooooooo, Ma’am! I’s got to have SOME money”- Cotton and Chick Watts, “The Black And White Minstrel Show” (1978)

“Even though, most of our albums are poorly promoted / And all the magazines probably won’t even quote it” – Phonte, “Still Lives Through” (2005)

It is a strange thing to see your skin everywhere. Even in places it isn’t. I don’t know how to describe this to someone who may not understand it, except to say that I looked in the mirror this morning and I didn’t only see myself. I, of course, don’t mean this literally. I mean that I know how easy it is for my skin to sell, as long as I’m not the one selling it. It would be almost too easy to give a history of Minstrel Shows, or to even call it history, as if blackness for disposable entertainment isn’t still a profitable enterprise. Which is all that one really has to understand when approaching the Little Brother album named after the act born of white performers painting their faces black and putting on tattered clothing before dancing and playing up black stereotypes to white audiences for laughs.

It is considerably harder to discuss and unpack the demand for relentless and always present black performance. A demand so firmly rooted in the history of our country that the performance itself has never needed to be from a black person, just someone willing to wear whatever costume will fool an audience for a night. Sometimes, for a week, or even a lifetime. And it is often a very specific form of black performance that we see craved. Sure, in 2015, it isn’t (always) the literal slather of black paint on a white face, or a bumbling black character, eyes wide and tap dancing onto a wooden stage saying things like “Yes’m!” while being casually berated for a round of laughter from a white audience. But there is still that same eager audience, having survived generations, pushed to the front of their seats, waiting to hear the steady tapping of hungry black shoes, making their way onto the stage in front of them. Or shoes worn by anyone willing to play the part, what we believe blackness exists as in hip-hop, or the films where we are servers, or helpers, or dead. America’s desire for black entertainment is never about black excellence. There is no punchline in silent, everyday greatness. The diplomas lining a mother’s wall, her living children and their living children, laughing around a Sunday dinner table. The punchline is in the loud failures. The punchline is the dropped plate. The punchline is poor man who needs work and will subject himself to anything to get it. The punchline is the black body that stumbles and falls, and doesn’t get back up again, even after all of the lights cut off. And the audience, weary from a night of laughter get up and go back to their homes.

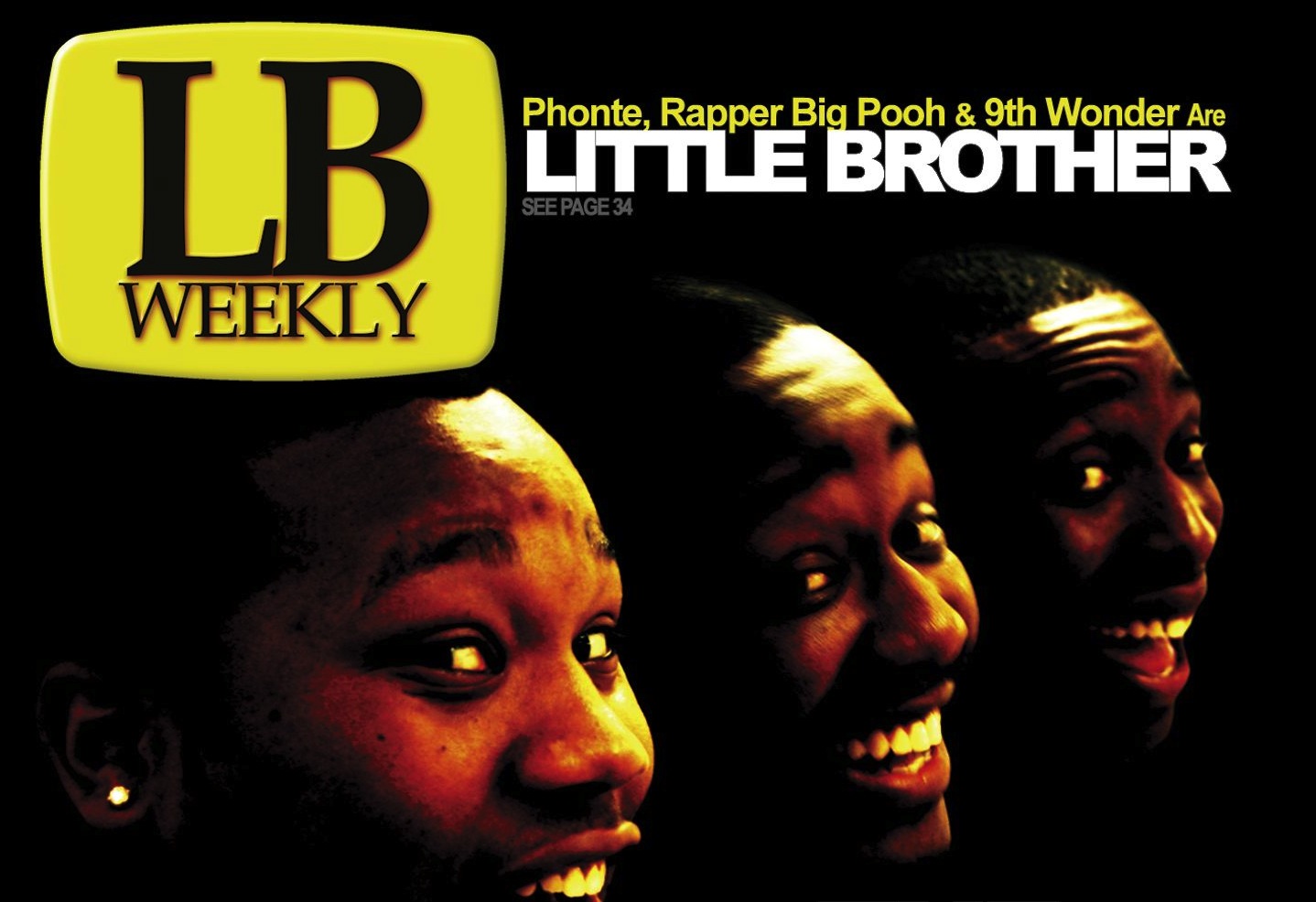

There are few things more powerful than reclaiming the joke without embodying the joke. To look at Little Brother’s titanic sophomore effort, The Minstrel Show, and merely reduce it to an album of finger-wagging at the hip-hop establishment is reductive and, frankly, boring. It also is hard to avoid in discussion of the album, largely due to its format and structure overshadowing the music for lazier listeners. The album uses the concept of being a fictional television network, UBN (standing for “U Black Niggas” Network), which overdramatically spoofed elements of black popular culture at the time of the album’s release. The album begins with a welcome to the network, before launching in to a playful, yet catchy chorus of “We’d like to welcome you to everything there is to know /This is our life, this is our music, it’s our Minstrel Show” backed by a glorious sample of “No Stronger Love” by the Floaters. Even the cover of the album itself stands out. Phonte, Rapper Big Pooh, and 9th Wonder grin, their dark faces against an even darker background, the text below them promoting “The Minstrel Show” as a “new hit sitcom” (on the aforementioned UBN, of course).

The album almost demands you to take it seriously, in spite of all these things, and more. Phonte taking on his alter-ego of “Percy Miracles” and singing comically overwrought R&B ballads during an album interlude. The greatness of The Minstrel Show as an album is how convincing it is. If I had to talk about the music, I would. If I had to say what we already know, that 9th Wonder is perhaps the greatest living producer in his genre, that Phonte and Big Pooh have a tension that pulls them to greatness, I would be glad to. I would talk about the run from “Beautiful Morning” to “Lovin’ It,” and how there is maybe no better stretch of songs on any hip-hop album I’ve ever heard, how right after that, we get “All For You” where Big Pooh lays his childhood at our feet, and it opens a window that so many of us know, and it does not close until the airy refrain lifts us from whatever guilt we were chained to. How the album closes out with the frantic “We Got Now,” where you can almost feel the pot boiling over, you can see the edge of the cliff approaching, and you stop right as the dust cloud kicks up behind your burning heels.

The Minstrel Show is a masterpiece. Like the history of minstrelsy itself, it does it a disservice to pretend that this album is a part of history, one that we cannot see, or one that we cannot feel. Which is perhaps why it was always urgently serious, even with its tongue firmly planted in its cheek. The album does hard work to unearth the history of the black stereotype for pay, and how it deeply affects communities. It takes the joke of the minstrel show just far enough, without dancing. It drags you to the theater, lets you hear the feet tapping, but never gives you the stumbling black performer. Instead, it gives you the full spectrum of a whole and complete black experience. The humor, the melancholy, the loss, and victory. In doing so, it acts as a mirror. It turns the act back on us, the audience. All great art interrogates, by any means it has to. This isn’t only about the music, because it doesn’t have to be. It’s about what The Minstrel Show asked of its audience. It’s about what minstrel shows historically asked of their audiences. And it’s mostly about the guilt that rests at the intersection of those two things, when we see our own reflections, and we have to ask ourselves, what’s so funny, anyway?

I don’t necessarily miss Little Brother, which is rare for me to say about a group that I truly loved when they were together. Part of that is because they have all gone on to do great things since their 2010 breakup. Another part of that, I think, is because their legacy is cemented. They are great to those who got to witness their greatness, who saw them at their most fearless and ambitious. It’s true, The Minstrel Show wasn’t the commercial breakthrough that we all were expecting and hoping it to be. BET (a very real network) refused to play the video for the lead single, “Lovin’ It,” allegedly because they deemed it to be “too intelligent.” There were conflicting issues with the album’s ratings, most notably in The Source magazine, and their label, Atlantic Records, seemed to abandon the album’s promotion entirely. And still, in their now very separate worlds, I imagine they look out at the landscape of popular culture, where black is still entertainment, but being black is still dangerous. And I imagine they throw their heads back, laugh a little bit, and whisper we tried to tell y’all.

And some of us are still listening.

Support our site: Buy this album at Turntable Lab