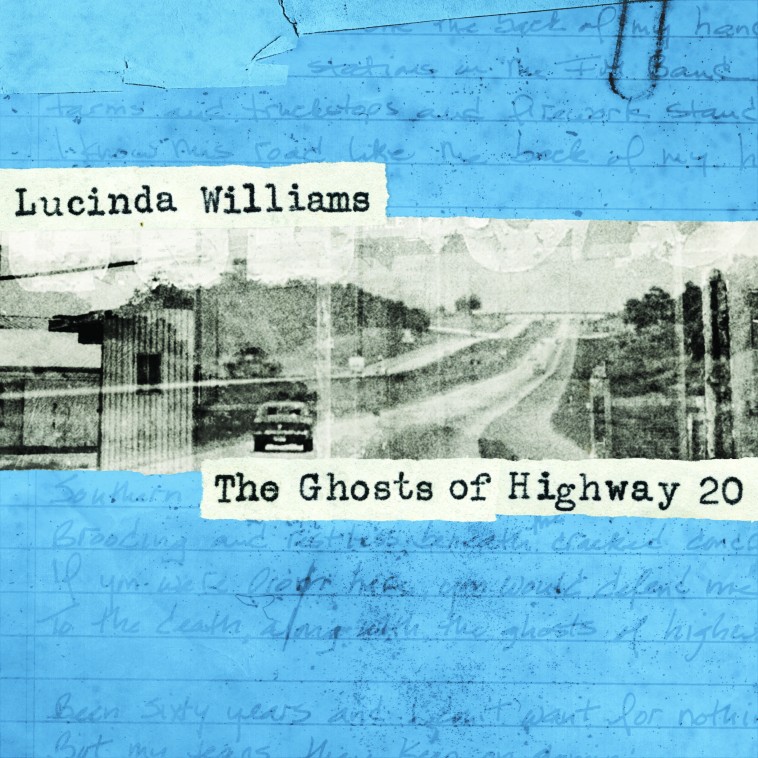

Lucinda Williams : The Ghosts of Highway 20

“You couldn’t cry if you wanted to,” Lucinda Williams sings on the first track of her twelfth studio release, The Ghosts of Highway 20. The song’s called “Dust,” and it sets to music a poem by her father, Miller Williams, who passed away on New Year’s Day 2015. Behind her a loping drumbeat rambles as she circularizes her settling thoughts, and twin lead guitars roll and chime to whip the dust into clouds that won’t get too far off the earth. The song moves from what Kurt Cobain would call “the comfort of being sad” to convulsing exasperation, and at the end of its six-plus minutes you’ve been through as unsparing a mission statement as American music affords.

The Interstate 20 referenced in the title runs from deep West Texas to Florence, South Carolina, crossing the northern quarter of Louisiana and the hearts of Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia along the way. It’s a route with deep connections to Williams, stuck firmly to the earth but linking to some very mystic dark corners. It’s a conduit for Williams to present a patient, anguished meditation on elusive spirits and hard-bitten experience, and at nearly an hour and a half, The Ghosts of Highway 20 is as demanding an album as Williams has made.

In making an album where there’s almost no sense of release or relief (“Dust” is about as cathartic as it gets, and it’s track one), Williams has instead made her most intimate record. Her inimitable voice sometimes becomes a troubled, hushed instrument of cracks, rasps and whispers, inhabiting characters who have all given up looking for escape hatches. The most stunning example comes right up in the second track “House of Earth,” a flat-out insane adaptation of an unused Woody Guthrie lyric about a Southern gothic courtesan. Williams’ vocals approach hypnotized drone as she carves out a come-on that’s unsettling in its exactness: “I’ll wash your feet a couple of times a day ‘til all your old time sorrow melts away/You’ll leave some drops of honey on my couch, I’ll leave a couple dollars in your pouch.” The unnerving narrative says a lot about the naturalism of frank sexuality, not to mention a heretofore unseen aspect of Guthrie’s writing.

Elsewhere Williams’ songs of experience take on several characters whose despair is differentiated by degrees. “I Know All About It” has the voice of a caustic instructor to someone who’s just learning how to not take care of herself (“I know about the pain and all of that jazz”) as a sarcastic swing falls in behind her. “Death Came” and “Doors of Heaven” are on different sides of eternal rest, alternating the despair of grief and a near-mocking demand for post-life rapture. The long folk dirge “Louisiana Story” is a heartbreaking portrait of childhood framed by quick pleasures and marred by Biblical violence, and a cover of Bruce Springsteen’s “Factory” is even more downcast than the original.

If the downbeat mood and Williams’ pared-down lyricism look flat so far, that’s because we haven’t discussed the band yet. What keeps The Ghosts of Highway 20 from unfettered disheartenment is the incredible empathy of its players, most notably guitar heavyweights Bill Frisell and Greg Leisz. On track after track they form an interlocking commentary that lends sweet counterpoint to the unadorned melancholy of Williams’ tales, matching her intimate confidence with ringing clarity. Honing in on their three-way conversation with Williams’ voice, buffeted by the appealing caution of drummer Butch Norton, is the absolute key to getting the most out of The Ghosts of Highway 20. Frisell’s and Leisz’s sparring on the angry “Bitter Memory” (sans drums) puts their vocabulary in plain view; their working in tandem to hold Williams up in the starkly beautiful “Can’t Close the Door On Love” is the closest the album comes to absolution.

The nearly 13-minute blues-rock closer “Faith and Grace” steers the album towards a covenant, drawing a possessed, shakily intense Williams towards a cryptic pact as Frisell plays every trick he knows. Williams’ spiritistic chant “that’s all I need/that’s all I need/that’s all I need” becomes a mantra that’s still unsettling: a murmuring last resort for her to “get right with God,” a direct quote of her song of the same name from 2001’s Essence. It suggests that even after nearly 40 years of making some of the most consistent American music around, her most urgent convictions are only now coming to the surface. Even with its message in plain view, The Ghosts of Highway 20 is a challenge to the soul.

Similar Albums:

Joe Henry – Blood From Stars

Joe Henry – Blood From Stars

Jason Isbell – Something More Than Free

Jason Isbell – Something More Than Free

Richard Thompson – Still

Richard Thompson – Still

Paul Pearson is a writer, journalist, and interviewer who has written for Treble since 2013. His music writing has also appeared in The Seattle Times, The Stranger, The Olympian, and MSN Music.