“World In My Eyes,” the first song on Depeche Mode‘s Violator, begins where many songs in the band’s catalog eventually end up: in the bedroom. Vocalist Dave Gahan offers a depiction of sex that’s romantic in the grandest sense of the word, conjuring panoramic visions of highest mountains and deepest seas via sensual touch. “Let your mind do the walking/And let my body do the talking,” he sings, displaying a level of confidence reserved only for rock stars. And yet in its deep throbs of synth and ecstatic exhalations of triggered snares, for the duration of its four and a half minutes, you can’t help but believe him.

In their earlier days, Depeche Mode didn’t shy away from matters of sensuality, but there was a level of transgressive irony to those earlier songs that kept them at arm’s length. In 1984’s “Master and Servant,” Gahan recited an instruction manual for sadomasochism that read like an anticapitalist retro dance craze, while “Lie to Me” juxtaposed ideas of craving sex from an unfaithful lover to the unfulfilled promise of “some great reward” from a factory employer. Though once they mastered the art of the sensual goth jam, it became something of a signature—I once saw a dancer do a striptease to their 1997 single “It’s No Good” while doing research for a food review (…it’s a long story). “World In My Eyes” is fantastical, certainly, but it’s intimate in a way that even the sexiest songs in Depeche Mode’s catalog never were, both in lyrical focus and the luxuriousness of the sound, velvety and lush rather than bearing the icy touch of industrial club infrastructure.

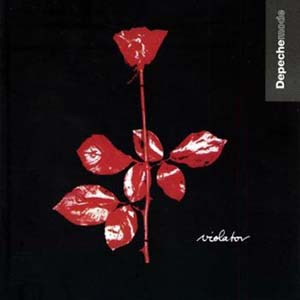

It’s an ironic curiosity in itself that the biggest and most ambitious album of Depeche Mode’s career at that stage is likewise the one that feels the most exposed. Violator is more interior-focused than most of the group’s other releases, which seems almost oxymoronic in the context of being the biggest album by a band at the peak of international stardom. But as their stages gained more square footage and their audience eclipsed the horizon, Depeche Mode worked to close a gap, bringing the listener deeper into the world of their creation rather than broadcasting it on a screen from 1,000 feet away. Violator is luxurious, almost tactile, given depth and breadth without sacrificing the larger-than-life showmanship they had built in front of a vastly growing audience of fans curious enough to reconcile S&M imagery with pop immediacy.

The peak of an upward arc that began with 1983’s Construction Time Again, Violator saw Depeche Mode fully realizing the potential of their dark synth-laden aesthetic, finally putting to rest (for the most part) the most cynical of criticisms aimed at the band from the beginning. The UK group first rose to prominence during the “New Pop” era of the early ’80s (better known stateside as New Wave) alongside groups like The Human League and Soft Cell, guided by Vince Clarke as their primary songwriter. In the beginning, the pristine veneer of the group’s synth-pop singles drew little in the way of acclaim or critical respect. Rolling Stone‘s David Fricke dismissed debut album Speak and Spell as “PG-rated fluff,” and after Clarke left to form Yazoo and eventually Erasure, Martin Gore took over as the group’s main scribe, again, to initial disappointment: Melody Maker called the group’s sophomore album A Broken Frame “vacuous.” These are, perhaps, bog standard criticisms for any group at the time that preferred synths to guitars, but as the band embraced more adult themes of social commentary and leather harnesses and cozied up to their dark side, they found the soul in their ARP 1600 after all.

Violator provided the most sumptuous temple imaginable for the band’s liturgy of sin, sex and salvation, as firmly established through their two prior albums, 1986’s Black Celebration and 1987’s Music for the Masses. They recorded its nine songs in five different studios with co-producer Flood—whose production prowess is all over later marvels of alternative architecture such as PJ Harvey’s To Bring You My Love and Nine Inch Nails’ The Downward Spiral. Fittingly, they christened this sanctuary with a satirical banger of a first single that offered a pitch for a private savior. “Personal Jesus” juxtaposed bluesy twang with the group’s cheeky sense of irony in an act of delicious blasphemy, beckoning listeners to “Reach out and touch faith” in the manner a televangelist might. It proved somewhat prophetic in an unexpected way, preceding a riot at a signing event in Los Angeles that drew thousands more fans than anticipated.

Few other songs on Violator feature that same kind of tongue-in-cheek irreverence, instead exploring the open space between introspection and desire. The album’s second single and candidate for Depeche Mode’s greatest song, “Enjoy the Silence,” leans farthest toward the former and revels in quiet solitude, acknowledging the fleeting nature of a perfect moment in the understanding that opening your big yap can only ruin it. Pulsing at 132 BPM and encased in grand, gothic electronics, it’s undeniably a synth-pop creation, but it features guitar—however tastefully—more prominently than on previous albums. It doesn’t by any means evoke the outlandish extremes of heavy metal, as the group suggested via the album’s winking title, but the song, along with other tracks like “Policy of Truth,” offered a glimpse at a more overt embrace of more conventional rock instrumentation as evident on subsequent albums like 1993’s Songs of Faith and Devotion. Yet for all its earnestness, its memorable video clip retains the group’s sense of humor, depicting Gahan as a monarch setting up a folding chair in remote locations.

Matters of the flesh are never far from the surface and often veer on being “pervy,” as Gore himself once described “Blue Dress” (“Say you believe/Just how easy it is to please me“). “Waiting for the Night” splits the difference between that song’s above-ground lustfulness and the serenity of “Enjoy the Silence,” an ambient dirge that finds solace “when everything’s dark.” It’s one of two lengthy songs on the album that best reveals the progress and depth of Gore’s songwriting a decade into their career, as well as Alan Wilder’s deft touch in their hypnotic arrangements. The other is “Clean,” a stunningly ominous waltz inspired in part by Pink Floyd’s “One of These Days” that pairs an eerie goth-pop mood with psychedelic flourishes. Amid Gahan’s reassurances that he’s “the cleanest I’ve been,” there’s an undercurrent of menace about it, which in hindsight might have something to do with his own struggles with heroin in the half-decade or so that followed.

In “Waiting for the Night” and “Clean,” as with the entirety of Violator, there’s a sense of both the visceral and the cerebral at play, an entire nervous system at work from the tangible to the ephemeral. It’s the difference between showing and telling, in writerly terms, but more than that it’s the difference between being a promising band and a great one. Violator is their monument commemorating that arrival, a sumptuous shrine of sense and feeling that converts distance into depth.

Note: When you buy something through our affiliate links, Treble receives a commission. All albums we cover are chosen by our editors and contributors

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.