Alone with yourself: A conversation with Emma Ruth Rundle

Emma Ruth Rundle is taking a moment to catch her breath. The singer/songwriter and member of Los Angeles shoegaze trio Marriages is laying low in Montana after several weeks of touring in Europe in support of Sargent House labelmates Wovenhand. She’s also nursing a head cold, but all things considered, she’s in a good place—spending time friends and family, surrounded by nature while she waits for her Portland apartment, currently being subleased, to be vacated.

Just one year ago, she found herself in a scenario almost the direct opposite of where she is right now. While finishing up the songs on her new album Marked For Death, she was living alone in the desert, in a bitter cold. She was playing and writing music every day, which when completed resulted in the heaviest album of her career—both sonically and emotionally. It’s a richly layered, often beautiful, sometimes harrowing document of a particularly dark year in Rundle’s life. Loosely speaking, the record finds her tackling love, loss, mental health, loneliness, death, self-destruction and a pervasive sense of doom in tones both elegant and immense. She’s hesitant to go into detail about the circumstances that informed Marked For Death, but in a phone conversation during her brief stay in Montana, she confirms that it’s all based in real-life events.

“The record is autobiographical,” she says. “We’ll just leave it at that.”

Marked For Death is Emma Ruth Rundle’s biggest solo effort to date. Following the ethereal, experimental guitar sounds of the mostly instrumental album Electric Guitar One from 2011 and the more fleshed out, dream-pop sound of 2014’s Some Heavy Ocean, Marked for Death is the album of hers that contains the widest dynamics between sparse, gentle balladry and thunderous climaxes. The single “Protection” features the most immediate chorus on the album, crashing with the density of her other band, Marriages, while closing track “Real Big Sky” is just Rundle’s voice and guitar, one of the simplest and most devastating moments on the album.

Initially, Rundle’s plan was to record an album of just guitar and voice, but ended up taking a different tack after writing the leadoff title track. That song became both a stylistic and thematic keystone for the record, its powerful guitar punch providing a backdrop for an ill-fated protagonist: “Who else is going to love someone like you that’s marked for death?” The depth and darkness of the song led to Rundle putting more of her own life onto the record, and as it came together, she found herself more directly channeling certain harsh or heartbreaking experiences.

“I think that the events that took place in the real world…dictated a whole series of events that laid the ground for me to live in a way to write all these songs that have these themes,” she says. “Love and loss, and a lot of other things going on in the material. Alcoholism, all this other dysfunctional stuff. It was sort of more the real world. That song is a good beginning point.”

While the seeds of Marked For Death were planted shortly after Rundle’s 2014 album Some Heavy Ocean, she did much of the writing for the album during a self-imposed isolation in the California desert during the winter of 2015 and early 2016. She’s quick to dissuade any romantic notions of what that entails—no parties at the Ace Hotel, no glamping in a climate-controlled yurt. She essentially holed up in a house for a couple months without even seeing much life at all outside.

The loneliness and starkness of the landscape ended up informing the album to a certain degree. It was already shaping up to be an emotionally draining work, based on the songs that Rundle had written before her exile. Yet the quiet and emptiness pushed her deeper into that darkness to a degree, and it resonates through the album’s eight songs. You can almost picture the open skies and hilly roads unfolding in the distance in songs such as the slide-driven waltz “Medusa” or the dreamy, open space of “Furious Angel.” But while Rundle came out of it with an album featuring some of her most beautiful material, the experience of camping out in a barren locale took a psychological toll.

“People keep using the word ‘bleak’ with this record. And you know, the landscape was bleak,” she says of her surroundings during the creation of much of the album. “I ended up living alone for a couple months. It’s a high-elevation desert. You could see the mountains. It’s very fashionable to go to places like Joshua Tree, if you’re from Los Angeles. A lot of people go out there, and there’s studios and there’s a hippie community. You can go out and get some vegan food. This is not what that is, at all. It’s not a million miles within that kind of thing. It’s very cold. There was a stove that I was having to put wood in to stay warm. I don’t know. I was drinking a lot. It was grim. I think it was very grim, and because I was out there alone a lot of that stuff went unchecked.

“I’m sitting here looking over this lake in Montana right now and there’s this feeling that things are alive,” she adds. “The season’s changing here and there’s an ecosystem. But the desert is like a big empty mirror. I don’t know. It’s not the kind of feedback you get from a landscape when you’re in a forest. It’s bleak. It’s gnarly. It doesn’t give you anything. There’s no distraction there. You don’t sit back and enjoy the weather. You have to be alone with yourself in such a real way.”

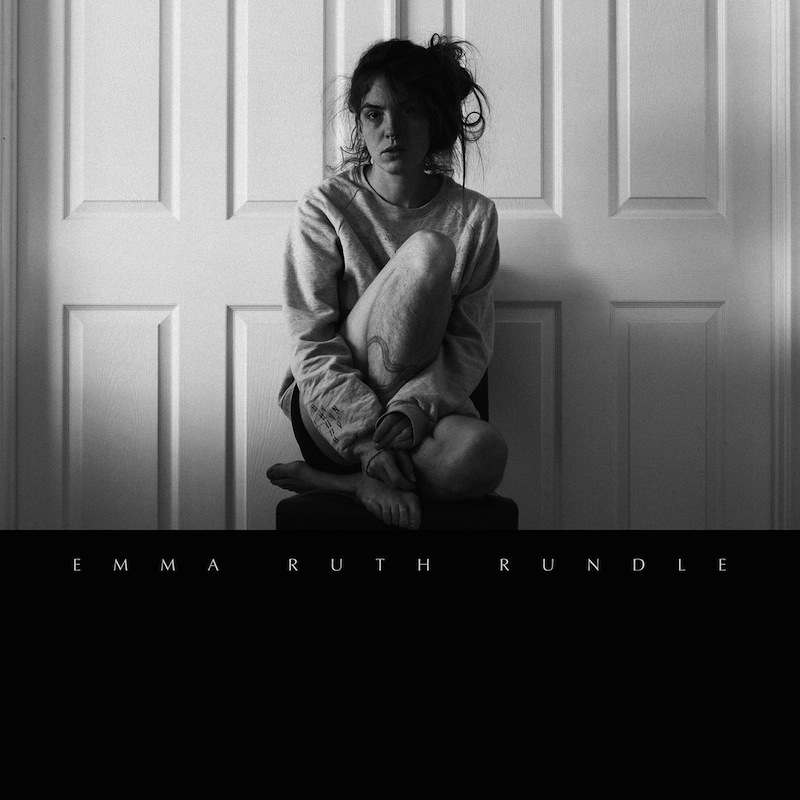

The cover art, itself, of Marked for Death is a kind of window into Emma Ruth Rundle’s state of being during the album’s creation. It’s a simple self-portrait in black and white, shot during her desert stay, during which she documented much of her experience via photography (a hobby she took up for the sake of creating something without worrying about it generating any income). The look on her face is stoic yet evocative. She isn’t made up for a photo shoot—a press release describes the shot as “unglamorous”—but it feels intimate. It brings the listener even closer into a personal space that performers don’t always give their listeners access to. It’s also a reminder of where she determined she needed to go on a personal level.

“There’s something about that photo that’s very poignant,” she says. “That’s the time when the songs were written. That’s who I was then.”

“I think I got to a serious low—mentally, physically, emotionally and spiritually. Almost at a zero,” she continues. “And I had some health problems earlier in the year, so it was almost like a breaking point. It had to be the end of something. I had to make changes toward a healthier lifestyle and pursue some kind of happiness. It’s unsustainable type of existence. I cannot write songs that are like that forever. That’s not sustainable. Maybe it was therapeutic. But there’s a whole other side to these kind of things where you perform these songs live and it takes you backward into this space in my heart. It’s almost like a backslide. But I was never not going to write the music because I might have to play it down the road.”

Emma Ruth Rundle has been returning to that vulnerable personal space while playing these songs on tour in Europe, and will again in the United States in 2017. But she’s traveled a great distance, spiritually, since writing Marked For Death. It’s an honest record, and one that directly represents a specific time in her life. On some level, perhaps, it’s an album she had to make, but it’s also a work with themes that can apply to a listener’s own experience. The catharsis for her is real, but it doesn’t necessarily belong to her. That catharsis is for everyone.

“I think one of the great things about music that has lyrics is that the listener can take whatever experience they’re having and interpret the lyrics through the filter of their own experience,” she says. “I think a lot of the themes are pretty simple and universal. I did not set out to make high art. It’s very human, very from the dirt. Very low vibration kind of themes. And that it’s relatable. That’s one thing I certainly love about music, growing up when i would hear lyrics I’d make up my own stories for what I think the stories were about. I’d never want to take that away from anyone.”

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.