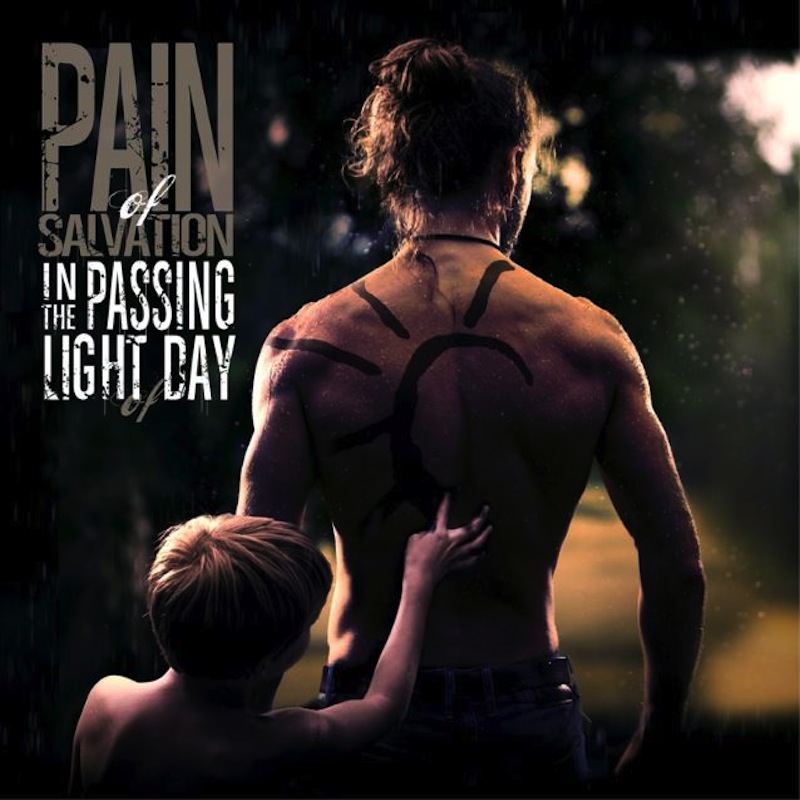

Pain of Salvation : In the Passing Light of Day

Prog metal has had a bit of a renaissance in recent years. Groups like Mastodon and Baroness spearheaded the change, one deeply proud of their prog influence and plaudits and the other just as progressive if a bit more squeamish about the mantle. Indie rock saw similar influence around the same time in the mid-2000s; Radiohead was being outed more and more as modern progressive rock band, proving the vitality of those ideas, while the Decemberists were more readily willing to adopt the title, influences and all that would mean for their music to follow. Likewise, artists such as Meshuggah, Ihsahn and Devin Townsend have been putting out records to progressively more critical acclaim, not only in the underground metal and prog sectors but also indie and mainstream. Hell, even Kanye West, Beyonce and A$AP Rocky are incorporating progressive concepts, textures, song structures and sonic palettes into their music and succeeding on a massive scale, not only critically but also culturally.

Pain of Salvation proves with their new album the frustration of missing out on the critical and cultural reevaluation of progressive music in general and progressive metal in specific. The songs on In the Passing Light of Day are in the standard milieu of the band: emotionally and texturally driven, where instrumental theatrics and fireworks are not avoided but likewise tilted toward elaborating the emotional color of the track rather than being superfluous and distracting. Pain of Salvation wield odd time signatures like weapons, destabilizing what once was stable and whole, grooves shuddering and over-extending or else breaking off into jagged edges before their natural ends. This replicates the emotional palette of the songs, focused on introspection and self-reflection and the bitterness, the sourness of resurfacing pain and love.

Pain of Salvation have always traded in the concept album, each record since their debut constructed around some kind of theme or plot. While certain buzzkills may find themselves cringing at this point—wrongly rebuking in their hearts the inherent theatricality and drama of conveying emotions and experiences through song—Pain of Salvation acquits themselves even of these fears. The plots, when they exist, are often deliberately obscured, the lyrics of songs individuating too strongly to form a coherent whole in any other terms than palette and completeness. Daniel Gildenlow’s primary lyrical influences are writers like Leonard Cohen, Nick Cave and Joan Baez rather than the knuckledragging pseudo-poetry found through the history of rock (not that there’s anything wrong with it!), and it shows; it just happens to be married to music more often indebted to Jeff Wayne’s War of the Worlds or Jesus Christ Superstar or Dream Theater. The concepts are meant more to be a generative object, using the same fertile soil to grow individual songs so that, when arranged, feel they belong together more, fill out each other’s empty spaces. The recapitulations found here feel natural precisely because, simply, they are; these songs, being grown from the same generating thought and experience, necessarily reused certain elements in small amounts, because they were gesturing to and drawing from the same spaces.

The concept here is the near-death experience of Gildenlow. In 2014, he checked himself into the hospital due to a painful lump in his back that turned out to be necrotizing fasciitis. Those first 24 hours in the hospital involved him very nearly dying, progressively more involved treatments failing one after another, his symptoms progressing steadily in an illness that can take you from fully healthy to dead within three days. In the end, he received a surgery to remove a large section of flesh, deep down to his spine, and spent the remaining six months of his stay on heavy antibiotics and constant monitoring of the wound as it healed. The songs draw from that first day, of the emotions one faces as time arcs from diagnosis to inevitable health. It cuts itself short on either end, however; the musical and lyrical content of the first song imply a diagnosis and potential death sentence has already been delivered while the final song, a 15-minute multi-section love letter to Daniel’s wife, seems to end before health has returned, when death still seems possible.

Each of the songs hovers in that space, in the brutal epiphanies we seem only able to make when on the verge of dying. Those who have nearly died, either by suicide attempt or illness or accident, know this experience: the pleading with God, waves of fear and madness, involuntary memory, the unique brutality of reflection when you feel there now is nothing you can do to alter what it is you are seeing. It’s hard to accuse these songs of the same sins of the worst of prog metal; they are too sincere, drawn too clearly from a legitimately life-changing and real event from the songwriter’s life. Details abound that are nearly too specific to ever be extrapolated out to abstract listeners save for in sympathetic resonance, having lived through similar things. These lyrical details are enriching not for their own sake, but for the way they connect the things the songs clearly want you to feel with real events experienced by a real person, undercutting the sensation of affect and melodrama that can undercut more conceptual or programmatic music, progressive or no.

This would mean nothing if the music wasn’t any good, though. In this case, the album doesn’t betray itself. The music doesn’t follow precisely the pattern described by press releases promising a return to the harder-edged and more heavily syncopated progressive metal of their earlier years. Instead, the ideas explored on their Road Salt twin albums remain, to the benefit of the songs and the album as a whole. The band is wise enough to know when to offer knotty, high-energy, syncopated and heavily rhythmic progressive metal and when to kill the throttle, using the same sense of spaciousness and centering of melody found on the deliberately simpler tunes of Road Salt. There are a number of occasions where the songs will cut back to a solitary gentle piano or flute or mellotron, recapitulating melodies and musical ideas in slow-building cinematic fashion before returning to heavier spaces. Pain of Salvation keeps the tempos down, allowing songs to breathe and linger rather than attempting to purely dazzle or mystify with instrumental heroics; this tastefulness and centering of the melody and emotional intent of the song is what served them so well in the past and what has made their trilogy of records from the early 2000s spanning from The Perfect Element, Part I to Be so widely acclaimed in progressive and metal circles.

The album unfortunately loses steam in the back half, the songs sounding at moments like musical retreads of previous studio records. Ironically, this is where most of the repeated lyrical and musical leitmotifs from Remedy Lane are stashed, where the spirit and compositional style itself is more perfectly repeated in songs on the first half. This is not to say that the songs following “Reasons” and preceding the album closer are weak precisely; similar to Mastodon’s Blood Mountain, it is more that they are overshadowed by other songs on the record that the manner they satisfy on their own gets lost a bit when placed next to other, better songs. The album closer, as stated before, follows the tradition of epic length and emotionally savaging closing tracks that Pain of Salvation has nurtured since their early days. Its success comes, ironically, from the way that it does not pursue the doomy, gothic and highly emotional progressive metal of songs like “The Perfect Element” or “Beyond the Pale,” instead opting to pursue something closer to Leonard Cohen or Nick Cave.

Ultimately, we are left with a fine and emotionally powerful progressive metal album, skewing closer to singer-songwriter material. In an alternate world, Pain of Salvation is recognized for producing the kind of work Lou Reed and Metallica’s grossly ill-fated collaborative album Lulu was supposed to deliver, the melding of the theatrics and melodrama of the technical end of metal with the literary, emotive and thoughtfully arranged music of Lou Reed’s neck of the musical woods. Pain of Salvation remain one of prog metal’s absolute best, and its (unfortunately) best kept secret.

Similar Albums:

Opeth – Sorceress

Opeth – Sorceress

Karmakanic – Dot

Karmakanic – Dot

Steven Wilson – Hand.Cannot.Erase

Steven Wilson – Hand.Cannot.Erase

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.