Out of Range: Part Five—Where Are We Now?

Out of Range is a five part, in-depth exploratory series that covers the the history of emo. From its first wave to its current revival, on to the impact of the word itself on language and fashion, it’s a primer for understanding the growth of a genre in its totality, alongside the technologies and changing cultural values that allowed it to flourish.

The following is the final installment of an interview series with Tom Mullen of Washed Up Emo, a curator of emo history and, above all, an educator who has kept the dream of the genre alive through good times and bad times alike. Tom was gracious enough to offer his insight about the genre including its controversies and hidden histories.

Chapter 5: Where Are We Now?

Emo has, in a sense, transcended its origins. Its ownership has switched from underground ad-hoc, to community, to corporatization and back to community-driven once more. The genre, while immediately definable by a certain sound or lyrical quality or even tonal atmosphere created by fourth-wave artists, is more dynamic than ever. The genre designation itself has broken free of its own heritage, bequeathed to culture to be abused, generalized and misused for comedic intent and sometime startling ironic accuracy. Emo—the genre, the fashion, the community, the sense of mind, the slang—has grown to mean a variety of things to a variety of people. The effects of its cultural mutation and influence are easily observed.

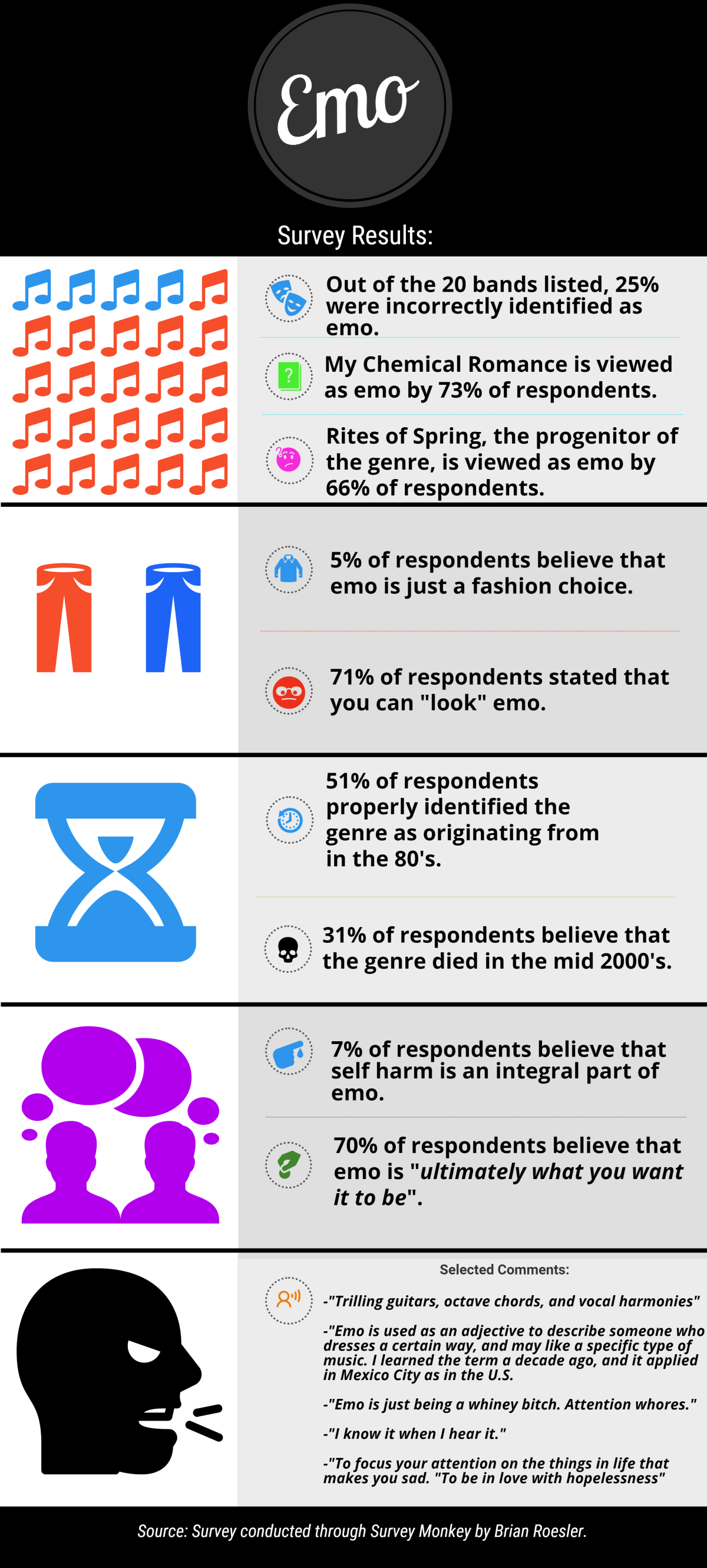

In order to reinforce this theory, a survey was conducted for the purposes of this series. Respondents ranging from ages 16 to 55, the survey revealed that the word has changed, and the thoughts about its conceptualization as well as its history are completely different.

But this is data. This is information that is only interpreted by the user, its relevancy and its import to them on an individual level is entirely variable. What is present from it, what can be gleaned from it, is a visual accordance of how respondents typically view or understand what emo is or should be. The corresponding and selected comments displayed above tended to mirror batches of other comments that oscillated between perceived stereotypes of the communities and fans, as well as a lack of understanding as to the progression of the genre and its history. Basically, emo was exactly what it meant to them during their youth, and now it seems alien and distant, perplexing even, the feelings are mutual for many.

Take recent articles from Noisey and Buzzfeed, where “emo” contextually is used in a completely different sense, one as a comedic statement, the other as a listicle that uses predatory nostalgia as its thesis. It’s used to address fashion, it’s used to address a state of mind, it’s ultimately used to discuss everything that was remotely tertiary to the genre of music itself, but rarely is it employed with a sense of history and a sense that anything emo existed before 2001. Which, to be fair, is normal. Genres, or rather communities, become touchstones for our lives only at certain points and rarely define us as adult consumers, functioning only for purposes of taxonomy.

As we progress as a society of consumers able to own and curate a massive library of digital music, we often find ourselves consuming not based on patterns of idolatry and fondness, or obsessive tendencies, but instead on what we genuinely enjoy. It’s too early to tell if the narrowing of tastes and acceptance of a plethora of artists in this modern music collective is going to end, or if as a culture we perhaps care less and less for the formality, history and inclusiveness of genre-based and -led communities.

Genres are after all, tools of convenience. We use them as ways to immediately identify a sound, a style, a theme, a process of artistic creation that mechanically speaking, has an identifiable genus. We are a species of taxonomists through and through. But, if we cannot agree as to what that genre means, or if it has gone beyond its intended usage through the nature of culture, ultimately maybe emo doesn’t mean anything at all. And, at the least, its definition and intent is malleable according to the person and the way in which they mean the word.

Washed Up Emo’s Tom Mullen said that “music is about community.” There’s an absolute truth to that. Music is about community. History is part of a community’s foundation, a shared appreciation for the topic for which communally there is a shared passion, and around shared passions there is always a profitable market. Which indicates the rise and ever present strange dichotomy between real emo nights, and popular 2000s music events that use the titled “Emo Nite.” In essence, not all Emo Nites are created equal.

After all, LA Weekly’s Art Tavana reported with a rather scorching frankness, the notion of Emo Nite patrons who were joyful to hear Kelly Clarkson. “It has the same energy of a live performance by a major pop star, except Kelly Clarkson isn’t onstage….Craig Owens, lead singer of Chiodos, playing Clarkson’s hit from an Apple MacBook Pro and surrounded by pretty, young and mostly drunken millennials on their iPhone 7s capturing the crowd’s bizarrely over-the-top reaction to a song that isn’t emo. Or is it? For the moment at least, being ‘sad as fuck’ to Kelly Clarkson feels about as emo as it gets.” Maybe Emo Nites, no matter their purity or their commercialism, have proven that emo as it stands for so many is a matter of nostalgia, of perception, of a wanton need to connect to something that was lost long ago.

Which is fine, right?

The issue, though, is that those that passionately defend the genre, and its community—those vanguards that stand for continued maturation of it and a need to maintain vigilance over its direction—aren’t wrong. They are necessary. They are the curators, the authorities, the Homeric champions of a world that is slowly slipping by us in some shape.

Emo was just a genre of music. It became a fashion. It became integral to the American lexicon, it became a mindset, it became a commodification, it became a DJ nite, it became consolidated nostalgia that preyed upon the millennials who with fondness in their hearts yearned for the carefree days of their youth. It was a cultural event that accrued social and aural currency alongside the proliferation of technology that helped communities bind together. No longer were fans isolated by a state line or city limits. It grew and bonded and changed together, just as the technology that helped it grow did as well.

So: what’s in a name? Well, everything and nothing. Emo is absolutely everything and a dense nothingness at that. Yet, its definition cannot be pinned down. Or at least from observable survey results, there are myriad ideas and definitions pertaining to the meaning of the word, which is more than music, more than fashion, more than culture or commodity or slang. It’s interchangeable and variable, a linguistic ball of yarn that cannot decide upon a singular meaning. If anything it really is a “feeling.”

Pluralism, along with the perfect dovetailing moments in a widened acceptance and promotion of obscure music culture allowed emo to flourish. It was the last of all “big things” and perhaps it’s fitting that for now, it’s the last of “big things” that corporations and labels alike tried to push in tandem, only to see it implode.

There will always be purists. There’s room for that, there’s advocacy for that. Yet, there will always something that is tangential to what those who have a larger scale of information or stronger belief in taxonomy will permit.

So what’s next? There’s no real way to possibly predict the course of music or culture. The two seem to inform each other in a way that is cyclical by nature. It is through careful reflection that we hone the accuracies of our predictions; perhaps we’re heading towards another rebounding of the effects of the third wave, perhaps such focus on a singular genre and its communities is no longer possible. Emo was, effectively, the last “big thing.”

Or, maybe, it’s all wrong. My hope is that, throughout this series, readers have been inspired to go out, observe, read, diligently explore the communities that are now in place digitally and locally to seek out knowledge that vehemently disarms this series, or at least calls into question its legitimacy in some sense. Everything is wrong, and everything is right. Or, there’s another answer. A better stance, a middle ground, in which purists, and taxonomists, community leaders and veterans, take a step back and begin to accept, begin to disarm the snobbish war and see emo as a greater part of not just music, but as a part of larger culture and history.

Emo is ultimately, whatever you want it to be. There are no critics anymore who will advocate for exclusivity, when the world itself is quickly becoming inclusive by the nature of how we consume. Emo can be a state of mind. Emo can be a fashion statement. Emo can be the music that just makes you feel something more than everything else. Emo is nostalgia for your youth. Emo is still the dirtiest word ever made in music, but it’s the one thing that everyone wants to be yet no one wants to own up to. It’s truly a beautiful thing.