Treating depravity: A conversation with Destroyer’s Dan Bejar

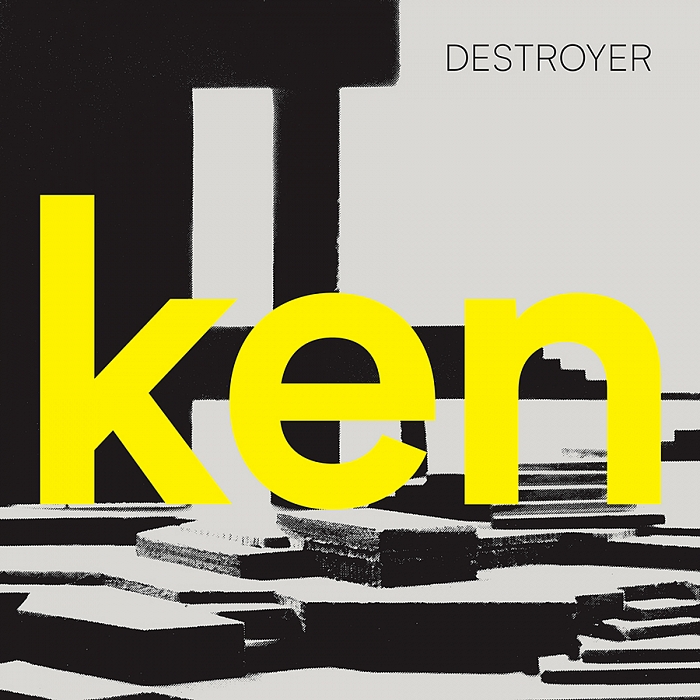

With each new album, Destroyer reinvents itself. The Vancouver-based band, led by singer-songwriter Dan Bejar, will release its 11th album, ken, on October 20. The album strips back the expansive, full-band sound of its predecessor, 2015’s excellent Poison Season, in favor of something colder and darker—a sound influenced, Bejar says, by the post-punk, new-wave music of his teenage years, the first music that he was “ravenous about.” It’s a grimy, enigmatic listen, though not without the wry, abstract humor permeates throughout Bejar’s entire discography.

Recently, Bejar spoke with Treble about the album’s “decadence and depravity,” his back-to-basics writing process for the album, and the “weird mystery” embodied by the album’s title.

Treble: Late last year, before you recorded this record, you road-tested a lot of these songs with a 15-date solo acoustic tour. Did workshopping these songs in a stripped-back setting end up influencing the direction of the album?

Dan Bejar: I’m not really sure. I know the conscious decision I made to try and play new songs and perform them in front of people, [which was] just based on the fact that I’ve never done that before. As to what kind of mood that put me in at the end of the night, when I’d go back to hotel and throw open my computer and try to [record] the song after having just played it, messing around with music… I don’t know. It still strikes me as a weird process, but it was cool.

It definitely put me ahead of the game as far as knowing how to sing the songs. I don’t know if this happens with everyone, but in my case, I feel like sometimes I get much better at singing a song after the fact, after having played it a bunch of times, which is generally too bad, because I usually record something and then the band will take that on the road. So I think with certain songs, especially the ones I played a lot, it kind of shows in the recording. I could be wrong about that.

Treble: This can be said about all of your albums, but ken is somewhat of a sonic departure from your earlier work. Did that darker, synth-driven sound emerge organically from the songs as you developed them, or was that a sound you intentionally shaped them into?

Bejar: I think it was a conscious sound that we definitely went in and chased. A lot of it has to do with [Black Mountain drummer] Josh Wells, who ended up producing the record. When I first embarked on that solo tour, I did have this vague plan of doing a solo record, in that I was going to just try and play the music myself. And I chickened out of that plan. I brought Josh in, who is somebody that I’ve played a lot of music with over the last five years, just because I trusted his recording skills. And I knew as far putting together some semblance of a rhythm section that he had key expertise. But it took about a day for him to grab a song and take it in a drastically different direction, even from the demos that I was putting together. I’d say over half of them bear no resemblance to my original plan. [Laughs]

So a lot of the record turned out more synth-heavy and more percussive than I had planned. Not that synths haven’t shown up on Destroyer records before—they have—but usually in a kind of gauzy, dreamy, ambient, new-age kind of way, like misty padding. These synths were much more in line with his aesthetic, which is kind of colder and darker and dirtier, more percussive, more in-your-face.

Treble: What ken has in common with Kaputt and Poison Season, at least in a sense, is a nostalgic element, where the sound recalls specific points and movements in music history. You’ve said that this one in particular nods to the end of the Thatcher era. Is that a conscious pursuit for you, to draw on those touchstones?

Bejar: I think when I was first starting to sing the songs or even write them, I was thinking a lot about the music that I first became ravenous about, which was pretty much strictly UK indie bands in the mid-’80s, late ‘80s. And aside from a couple of them, that’s stuff that I hadn’t really listened to much in the last 25 years, and I started listening to things like that again.

I started playing guitar again for the first time in 10 years. Before that, guitar was just an acoustic hum that I would gently strum to sing over if I was playing a solo show. But as far as thinking of it as an instrument in itself, an instrument to write a song on, that’s something I hadn’t really done since 2007, maybe, with Trouble in Dreams. I think that shaped the songs a lot, made them very simple and direct and short as hell. It’s probably shorter than any collection of songs I’ve done since the 1990s. For me, that’s the first thing I notice about the record. I can’t remember the last time I had so many two- or three-minute songs which have a real brevity to them, which in a way may have something to do with that kind of post-punk, new wave song, which is kind of English pop in its own way. That’s as opposed to the ‘70s stuff [from recent Destroyer records], which I think is a bit more expansive.

So yeah, it’s something I was conscious of… I think when I touch a guitar, I automatically go back to that era. It’s kind of foundational for me, and it’s also simple melodies played through basic but in-your-face effects. I will say also that Kaputt and Poison Season—if it has nostalgia, it’s not for eras that I was conscious of, while this is. This is music that I experienced firsthand as a teenager, while I never experienced [Roxy Music’s] Avalon as a kid, and I definitely never experienced, like, [Lou Reed’s] “Walk on the Wild Side” or ‘50s Sinatra records as a teenager—those are more like, conventions in my mind, or how I imagine music of a certain era to sound.

Treble: Even on Poison Season’s brighter-sounding songs, the lyrics maintained a certain sense of dourness. Ken’s sound is much darker; would you say that’s true of the lyrics as well?

Bejar: I think Poison Season is a more intimate, rambling record in a lot of ways. It’s not confessional, but somehow the writing is more personal. Ken [has] has a series of voices for different songs, which is not a normal way of writing for me, but it’s just how it turned out. I feel like there are songs on ken that are more explicitly negative than most things I’ve written in my life. There’s a lot of casual use of extremely negative terms, which I would say is me singing to my teenage self and that kind of extreme worldview that we come out of when we’re young.

That being said, most of the songs on ken can be broken down into three or four pretty simple categories. They all seem to treat either sickness, insanity, violence, or decadence and depravity—sometimes all mixed up in one song—in quite explicit terms. But those terms come up in every single song, I’m pretty sure, if you scan them lightly. And then there’s always a narrator or two who are just craving distance, isolation, just escape… Either craving, or preaching [for others] to get away.

Treble: You mentioned writing in different voices for different characters. How writing in that way different for you from the way you approached, say, Destroyer’s Rubies, which seemed much more personal?

Bejar: The process does not really change too much. I still am descended upon by language with some kind of melodic thread attached to it, and it makes my heart beat faster when it comes, so I remember it. And I string it together with other things like that, that feels right to me. It’s all a cyclical process that happens really fast when I sit down to try to do it. I will say that, because I’ve done this so much, whether I want to or not, I write with a certain craft in mind, so the language has become much more pared-down. I can’t help but think of what it will mean as music, as opposed to Rubies, which is the apex of [the lyrics] dueling with the music.

I don’t think that era is less musical, but I felt compelled for some reason to just spit out as many kind of images flashing upon my mind, as many as humanly possible, and yet still make it sound like music somehow, and phrased as music. That’s very different from Kaputt, and very different from—I mean, Poison Season had more words, but it’s still quite different from Poison Season, and extremely different from this last record. I was obsessed with images, man. I still am. It’s what moves me the most. But slowly but surely, the situations where that imagery lives seem to be getting more concrete. Maybe that’s cool, maybe that’s more typical of getting more into craft, which sort of happens as you get older.

Treble: Speaking of the album’s imagery, I’ve got to bring up the video for “Tinseltown Swimming in Blood,” which is an homage to the 1962 film La Jeteé. How did that imagery lend itself to that song, in your mind?

Bejar: I don’t really know because I’ve never had a second’s input into any video that Destroyer has ever made. I’ve literally just been like, “Tell me when to show up and where to stand, and then make sure when the video’s done that you send it to the record label.” It had nothing to do with me whatsoever, nor the video before that or the video before that. I really like how it turned out, and I was curious as to how it would work. I knew La Jeteé, I like it, and I definitely like the idea of something made from still black-and-white photography. And I liked the idea of dying at the end. But that’s really all I brought to it.

Treble: In the press release for the album, you mention that ken takes its name from the working title of Suede’s “The Wild Ones,” but that you’re not quite sure what compelled you to attach that name to this collection of songs. How much of the process of making an album is built on that sort of intuition, going beyond an ability to explain or put into words?

Bejar: I mean, all of it. [Laughs] All of it is beyond my ability [to describe]. When I talk about it, I hear the sound of compromise in real time. But for me, it’s about emotional resonance, just little pictures and trailers of my hang-ups and whatever poetic resonance my hang-ups might have. I can recognize the poetry in them.

The ken [press release] is a good example of something I never would have written had I not been steered by the first people who heard the album title toward legitimate dread, that here was going to be some kind of Barbie and Ken connection made. It had never occurred to me. I felt foolish for addressing and for writing about it, but I did. I got caught up in that hysteria. Because the feeling of seeing that “The Wild Ones” was originally called “Ken,” was a strange feeling. It’s not one that I expect people to understand, even if it’s like, “Imagine if ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ was called ‘Bob,’ or something.” It’s just the weird mystery and disconnect that happens in language and how three little letters can transform something and create a new hidden meaning or some kind of narrative that’s been there all along that you just never knew about.

The sad fact is, actually, during the process of doing some interviews, I found out what the real story is behind that from [former Suede guitarist] Bernard Butler himself. The truth is always so much more banal and useless than what it is that you conjure up in your mind, which is pretty much all I’m getting at [with the title], aside from just liking the sound of those letters for some reason, and thinking that it reminded me of a really old-fashioned English name in like, a Samuel Beckett play or something.

Treble: You’ll be playing your first shows behind ken in November. You’ve spoken before about how much you like the current, eight-piece lineup of Destroyer, but there seems to be less room for a full band in the minimalist arrangements of ken. So what does a live version of ken look like?

Bejar: Like you said, I have become really attached to that group that made Poison Season, and that’s been touring as Destroyer for the last five years. And so that’s the band, you know? There’s eight of us, and it does maybe feel like that’s a lot for some of these new songs, which are kind of a conscious exercise in minimalism. It’s as minimal as Destroyer’s probably going to get.

That being said, I think of the songs will lend themselves well to being blown-out and put through the wringer by us. It’s just the process of what this group does, just picking up a Destroyer song and kind of like, sniffing it. Either we’ll lay into it and it will be really fun, or we’ll try it and it won’t work, and we’ll just move on. But I’ve always been more about contorting material to the band onstage and not vice-versa. There’s ways that this band can conjure up space, for instance, that is different than the space we created on the album. And everyone plays on the record. [The album’s arrangement] is just kind of my insight into how an actual producer might work, building the songs up until they’re quite formed and then bringing people in to play in specific spots here and there—as opposed to the normal Destroyer way, which is just bringing each person in and having them play from beginning to end all over each song, and then go looking for what you like.

But for the live stuff, Destroyer has a long history of showing up and playing in a way that someone who was just into the last record we came out with would be like, “What the fuck is this?” It’s been a good 15 to 20 years of that, so even if the songs sound nothing like what they sound like on the record, I don’t think anyone at this point would be that shocked. They’re probably going to be a lot louder, which is kind of how I like to play. There’s not too many songs on the new record with a big noise. There’s a couple, but for the most part, there’s a steady, motoring vibe to them. But that’s just a launchpad, really, for the live show.

Good interview but Bernard Butler wasn’t just the pianist in Suede…

Fixed. That was weird

Guess I need to brush up on my Suede knowledge…

Fixed for real this time. It’s really easy to confuse Bernard Butler for Brett Anderson first thing in the morning.