10 Essential Late-Career Peak Albums

Longevity is a relatively new concept in popular music. Record labels always look to youth for the voices of the future and the paychecks of the present, but age is an inevitability. Only the greatest artists among us are able to channel their muses well after the grays start to grow in. Yet over time, it becomes increasingly more common to see artists catching a second wind late in their career. Some, like Tom Waits, never really stop. While others, like Kate Bush, go into hiding for long periods of time only to emerge with some of the best music she’s ever recorded. Recent years have seen releases of a number of standout albums from artists with decades of history behind them. Sometimes, unfortunately, that means their swan songs. Yet the flipside is how inspirational it can be to hear music so vital and so endlessly creative after so much has already been pressed to vinyl. This week, we honor music’s elder statesmen and -women by selecting 10 of the best late career albums by standout artists. Some are unique visions with unexpected stylistic flourishes while others are simply perfect additions to already impressive catalogs.

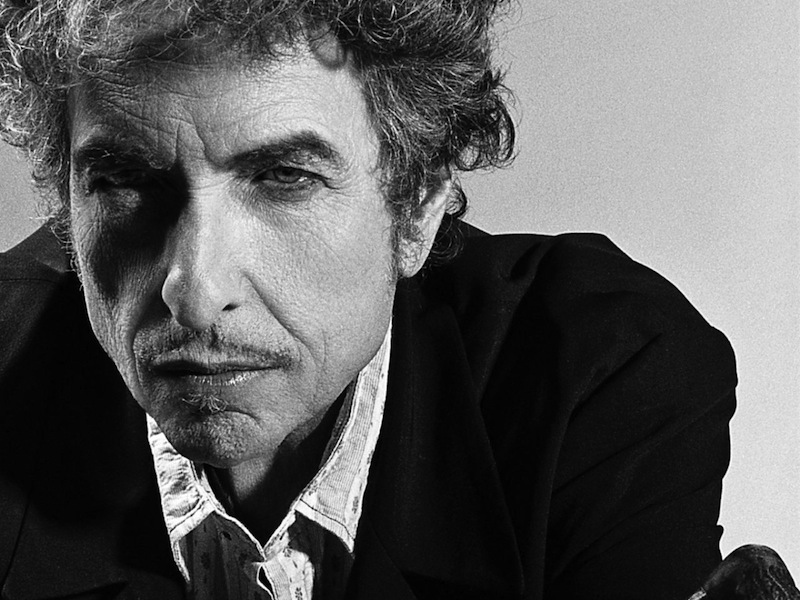

Bob Dylan – Time Out of Mind

Bob Dylan – Time Out of Mind

(1997; Columbia)

His last unquestionably great album had been 1975’s Blood on the Tracks, his ‘80s output had been hit-and-miss-and-miss, and by the early ‘90s he was content to record humble folk songs he didn’t even write. It’s tempting to think all that aimlessness was just Bob Dylan setting us up for Time Out of Mind, which came out of nowhere in September 1997. Producer Daniel Lanois stripped off all vestiges of Dylan’s ‘80s cleanliness, bathing him and his band with gritty echo and lots of space. You can practically hear wind howling in the background on every track. Dylan shied away, mostly, from his more elaborate style of lyric writing. Instead he focused on matching a plainly wearied but haunting voice with exactly the words it needed to say, especially on “Love Sick,” “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven” and “Not Dark Yet.” “Dirt Road Blues” and “Cold Irons Bound” were just slightly more uptempo, but still steeped in the album’s amber backglow. And somehow he wraps the whole affair up with the 16-minute-plus “Highlands,” half statement and half shaggy dog tale that probably tells you all you need to know about him, but shouldn’t be where you start. Everyone—critics, fellow musicians, the record-buying public—knew almost instantly that for the first time in 22 years, Dylan was unquestionably great again. – Paul Pearson

Johnny Cash – American III: Solitary Man

Johnny Cash – American III: Solitary Man

(2000; American)

Johnny Cash spent five decades of his life releasing albums, but in the ’80s and ’90s, he and the Nashville hit machine had long since drifted apart, his classic country sound no longer in tune with the glossy ballads and pop stylings that had since taken over. Yet when Cash teamed up with producer Rick Rubin in 1994 for American Recordings, Cash’s music was given new life and reintroduced to an entirely new audience. Thus ushered in a second period of fertile creativity and outstanding albums. That being said, picking one is sort of arbitrary, but American III stands out ever so slightly, if only for its impeccable collection of covers, including Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ “The Mercy Seat” and Bonnie “Prince” Billy’s “I See A Darkness,” each delivered with a breathtaking humanity. It’s an album of joy and pain, of darkness and of hope. It’s Cash in a nutshell. – Jeff Terich

Solomon Burke – Don’t Give Up On Me

Solomon Burke – Don’t Give Up On Me

(2002; Fat Possum)

One of the first names that pops up when you think of under-appreciated soul vocalists (see also: James Carr), Solomon Burke spent nearly three decades languishing in the back of connoisseurs’ collections without releasing much of note after his ‘60s classics. A contract with blues firebrand label Fat Possum brought him under the auspices of producer Joe Henry, who loaded Burke’s cannon with new tracks from songwriting heavyweights (Tom Waits, Van Morrison, Elvis Costello, Brian Wilson) and tamped the production to a scant roll to give his voice room to shine. Don’t Give Up On Me was a master class in maturity and fire, and netted the 62-year-old Burke his first Grammy in the aftermath. The songs were perfect matches: Waits and Kathleen Brennan’s “Diamond In Your Mind” was overpoweringly poignant, Wilson’s “Soul Searchin’” sounded like Burke hadn’t aged a whit, Nick Lowe’s “The Other Side of the Coin” was wise and willful, and the opening title cut broke your heart before you had a chance to sit down. Burke passed away eight years after its release, but not before he cemented his legacy with one of the oughts’ best soul albums from anybody. – Paul Pearson

Scott Walker – The Drift

Scott Walker – The Drift

(2006; 4AD)

After a series of poorly received country-styled albums in the 1970s, American-born British crooner Scott Walker slowed the pace of his output dramatically, eventually averaging about one new album every eight years or so. Yet the album Nite Flights, featuring the terrifying showpiece “The Electrician,” gave a roadmap as to where Walker would go next. Three albums and nearly 30 years later, he issued The Drift, a towering, avant garde masterpiece of modern horror. Akin to the classical works that scored The Shining with crooned vocals, The Drift merges satire with genuine dread, referencing 9/11 and Elvis Presley’s stillborn twin brother while giving humorous takes on the music industry, punching sides of beef for percussive purposes and speaking in a Donald Duck voice. It’s not a work that’s forgiving or gentle, nor is it for everyone. That’s an understatement, really. It is, however, a masterpiece. – Jeff Terich

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds – Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!!

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds – Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!!

(2008; Mute)

Given the recent sound and emotional atmosphere of Nick Cave’s past two albums (Push the Sky Away and Skeleton Tree, both sparse, bleak affairs), it seems like 2008’s Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!! might’ve been a semi-aberration. Or perhaps he wanted to make a Grinderman record with the full contingent of Bad Seeds musicianship at his disposal. Either way, Lazarus is a gleefully profane masterpiece that rocks harder than almost anything in Cave’s catalog. Cave scabrously reinterprets Biblical narratives, mocks writers’ pretensions (including his own), and offers all manner of seductions and surrealistic bon mots in some of his most complex lyrics ever. Those expecting goth hellraiser or balladeer Cave won’t find either here, but they will find one of this young century’s best rock records that has not an iota of the genre’s pitfalls—it’s rhythmic, intelligent and not infrequently hysterical. – Liam Green

Gil Scott-Heron – I’m New Here

Gil Scott-Heron – I’m New Here

(2010; XL)

The 16 years following the release of Spirits on TVT Records were largely unkind to the jazz poet widely heralded as a 1970s godfather to the rap genre. The man behind “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” dealt with an HIV diagnosis, drug addiction, and prison sentences throughout the 21st century. He kept touring and recording live albums during this time, but when he hooked up with XL Recordings owner Richard Russell he finally found a new spark of creativity as well as an outlet for it. Russell produced I’m New Here in stark contrast to GSH’s known brand of folksy, funky observations, instead opting for the kind of minimalism suggested by his label’s band-of-the-moment, The xx. A mix of grizzled studio banter, new and revised material, and bluesy anchors in “Me and the Devil” and “New York is Killing Me,” I’m New Here was a fresh look deep into one of the oldest of old souls. The following year it would launch The xx’s Jamie Smith into production superstardom of his own, remixing it into We’re New Here the following February, and serve as a fitting career epitaph for GSH himself upon his death that May. – Adam Blyweiss

Kate Bush – 50 Words for Snow

Kate Bush – 50 Words for Snow

(2011; Fish People/Anti-)

Kate Bush was all of 20 years old when she released her debut album The Kick Inside, which launched a decade of highly prolific, increasingly complex and powerful musical statements that eventually yielded one of the best runs of albums in the 1980s. After 1993’s The Red Shoes, however, Bush retreated from the limelight, long since having retired from performing live and focusing instead on being a mother. With 2005’s Aerial, she broke that dry spell with an ambitious, concept-driven double-album that marked a strong return, which she then topped six years later with 50 Words for Snow, released 33 years after her debut. It’s a delicate and ethereal album, romantic and melancholy. None of its songs carries the kind of anthemic power of “Running Up That Hill,” but in its stead are some of her most challenging and beautiful compositions. It’s an album whose loose winter themes have an appropriately delicate corresponding score. So while it’s worthy enough as an excellent late entry from a songwriter and performer that demands more patience than ever, it’s an essential album in part because it’s proof that Bush never stops evolving as an artist. – Jeff Terich

David Bowie – The Next Day

David Bowie – The Next Day

(2013; ISO)

After listening to Bowie for over 30 years, I felt it unnecessary to revisit Blackstar so soon for this list. Sure it was a great album, but Bowie’s b-sides and filler are better than the most artists’ creative peaks. The Next Day is comparably dark and it actually rocks pretty hard, so those two facts alone justify its placement here. The guitar tone invokes his classic Scary Monsters era of cosmic art-rock zaniness. Songs like “Love is Lost” not only find Bowie in a more intense place than his last album vocally, but remind the listener he is the Godfather of goth. This album has everything I want to remember him by as “Dirty Boys” packs a sexier slink to it that finds him smirking his way into the bedroom. If that weren’t already enough, the opening chords to “(You Will) Set the World on Fire” rocks harder than anything since “Hallo Space Boy” thus solidifying its place here. – Wil Lewellyn

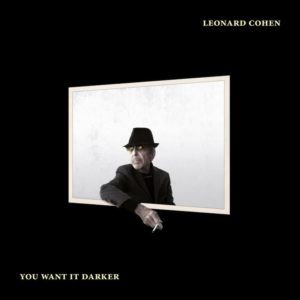

Leonard Cohen – You Want It Darker

Leonard Cohen – You Want It Darker

(2016; Columbia)

It could be said that You Want It Darker didn’t stand out as an album about death because Leonard Cohen had been so fascinated by the subject since his earliest records. On closer inspection, however, the album makes very clear references to his own imminent departure, with a particular recurring analogy to “leaving the table” and being “out of the game.” It came as the third in a stunning trilogy of albums that saw Cohen finally arrive at a place of contentment, albeit one that still allowed him to probe at life’s biggest questions. The older he got, the more sense he made, and the more his lyrics and vocal style mirrored each other. It is as if he couldn’t wait to reach this stage of life or career. – Max Pilley

Elza Soares – A Mulher do Fim do Mundo

Elza Soares – A Mulher do Fim do Mundo

(2016; Mais Um)

Brazilian singer Elza Soares has the kind of biography that could fill a half-dozen Behind the Music episodes, having been both a mother and a singer in her teenage years, a widow at 21, a chart-topping performer across multiple decades in Brazil and a performer at the Rio de Janeiro Olympics in 2016. At 79, she continues to explore experimental and bold territory, merging the samba rhythms of her early recordings with punk, rock and psychedelia on last year’s A Mulher do Fim do Mundo. The title translates to “A Woman at the End of the World,” and damn if it isn’t a prophetic, or at least culturally appropriate title. A frenzied and endlessly creative exploration of sounds both uniquely Brazilian and frequently chaotic, it’s the sound of the best damn party you could hope to be invited to as the world burns. And Soares herself is a vocally fierce and vital force, crooning and growling her way through the whole damn thing like nothing could stand in her way. She’s made it this far, yet from the sound of the album, who knows how far she could end up going. – Jeff Terich