Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode to Billie Joe” captured cruel detachment in the face of tragedy

Blood on the Tracks is a bi-weekly series that documents songs with dark histories. Sometimes they’re songs about something gruesome or terrifying, and sometimes they’re seemingly innocent tracks that are given a bizarre and sometimes horrific new life over time.

***

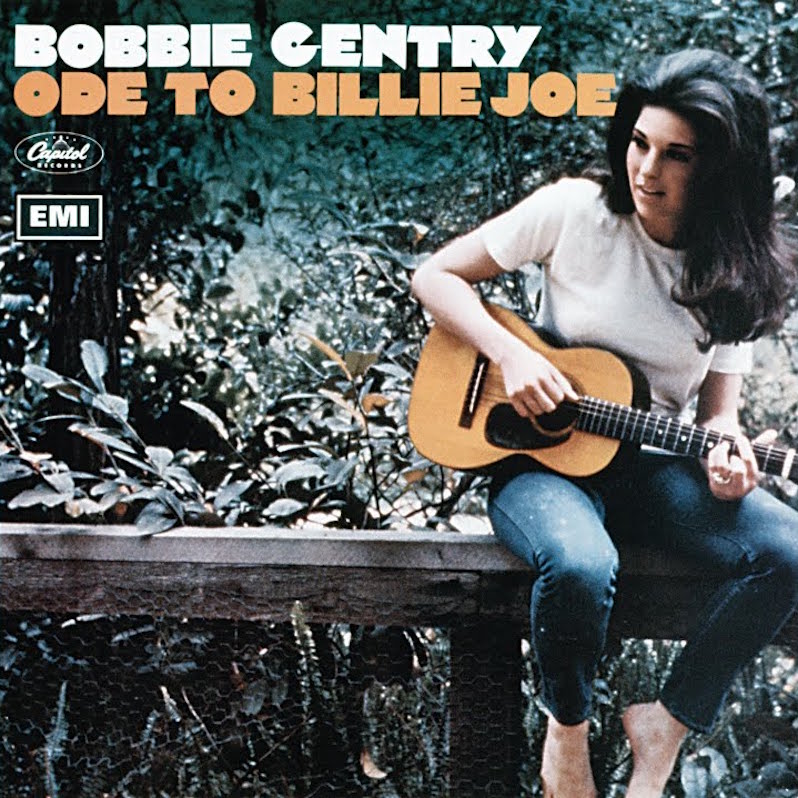

Bobbie Gentry‘s plan wasn’t to become the new face of country music. She had performed live and written songs, but Gentry’s intention was to get the attention of Capitol Records on the strength of her songwriting. Much as Lou Reed or Carole King did early in their careers, Gentry sought to become a songwriter for other people, which in both country and pop music is a practice that hasn’t changed much in 60-plus years. Yet Mississippi-born Gentry didn’t have a record company budget to make a demo tape with a professional singer, so she pitched Capitol with two songs she sung herself, “Mississippi Delta” and “Ode to Billie Joe.” It worked, if only a little too well. Capitol signed Gentry in June of 1967, and her demos officially became album masters for what would become her debut album. Only she wouldn’t be writing songs for country stars—she was the star.

Yet Gentry’s signing highlighted an interesting difference of opinion between what her label heard as a hit and what DJs and listeners preferred. Capitol’s interest in Gentry came from hearing “Mississippi Delta,” a swamp rock number closer to the prevailing tastes of the time, and a choice based on perfectly understandable instincts—her interpretive-dance-in-the-bayou performance of the song on the Andy Williams Show was probably already choreographed by the time Gentry’s debut album hit the shelves. Yet the song planned for the b-side, “Ode to Billie Joe,” ended up giving Bobbie Gentry her first hit, and a pre-internet viral mystery to go along with it.

“Ode to Billie Joe” isn’t a high-energy rock ‘n’ roll song, but a Southern gothic country/folk ballad with a chilling, at times humorous and ultimately poignant narrative about detachment in the face of tragedy. On paper it doesn’t seem like a hit. In fact, the original version of the song spanned eight minutes long and featured nothing but Gentry’s voice and acoustic guitar. And before anyone starts to bring up Dylan, remember that “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” wasn’t a hit either. Once Jimmie Haskell’s string arrangements were overdubbed on top of a four-minute edit of Gentry’s “demo,” however, it became clear to all involved that this was the song to push.

It’s a catchy song. A soulful song—at its core a simple blues/folk melody that provides an earthy canvas for Gentry to depict a tragic suicide in a small town in Mississippi. “Ode to Billie Joe” is something like the story-song equivalent of a bottle episode. We learn of the details of what happens only through the dialogue between family members gathered around a dining table. It happens gradually, the picture getting a little bit clearer through the commentary from the narrator’s mother and father, only in between minutiae like “Y’all remember to wipe your feet” and “pass the biscuits please.” But Gentry gets to the point early and repeatedly, ending each and every verse with some variation of “Billie Joe McAllister jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge.”

There isn’t any mystery about the death of Billie Joe—he died because he jumped off the bridge. But in the fourth verse a detail emerges upon which the events surrounding his death potentially hinge. As the narrator, stricken with grief, is hassled by her mother due to her lack of appetite, Mama lets slip that a young preacher, Brother Taylor, “saw a girl that looked like a lot like you up on Choctaw Ridge/And she and Billie Joe was throwin’ something off the Tallahatchie Bridge.” Here, essentially, is where the fascination with the story at the center of “Ode to Billie Joe”—and it’s certainly a captivating story—essentially capture’s the public’s imagination. What did they throw off the bridge? Gentry said in a 1967 interview that it’s the question she had been asked most by people who met her, with speculation that it was anything from an engagement ring to an aborted baby.

Gentry’s never revealed what that object is, though the narrative proved compelling enough to spawn a film adaptation nine years later. And on the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love, The Independent highlighted it as one of the songs that defined 1967, highlighting the mystery as part of its appeal. Indeed, it’s hard not to be wrapped up in that one small piece of the puzzle—the thing that might offer some kind of answer as to why this fictional character we know so little about decided to end his life by plunging off of a bridge and into the river below. And when paired with the masterful string arrangement—which acts as a storytelling device in itself, offering some very cool and frequently chilling effects like the trembling descent in key when Gentry ends the song with imagery of dropping flowers off of the Tallahatchie Bridge—the tale takes on a stylistic darkness that completes the picture even when the story itself isn’t entirely so clear.

But “Ode to Billie Joe” isn’t a murder mystery. It’s a study of grief and the absence of empathy, or in Gentry’s own words, an “unconscious cruelty.” The reason that the preacher saw a girl that looked a lot like the narrator on Choctaw Ridge is because it was her, and Billie Joe was her boyfriend, and now he’s dead. And nobody in her family seems to get that, or for that matter, care. She’s grieving and her mother tells her she needs to eat more. But she also can’t bring herself to say anything about it either. And a cruel twist of irony comes in the final verse, a year after Billie Joe’s death, when the narrator’s father dies and “mama doesn’t seem to want to do much of anything.” She’s given no empathy either, and this family stricken by two tragedies in the course of a year somehow just can’t or won’t offer each other support.

When you dig beneath the surface, “Ode to Billie Joe” has a sadness to it that taps into something everyone’s probably experienced at one time or another—how sometimes a person’s pain is simply inconvenient to others. But look, when I first heard the song, I was caught up in the mystery of what was thrown off the bridge too. It’s almost as if Gentry, who sings her tale as coolly and as detached as the family gathered around the dinner table, left it there as bait, if only to prove her point. And here we are, overlooking a quiet moment of grief because of a possible red herring.

Not that any of us can be blamed, really. “Ode to Billie Joe” is just too fantastic of a song, too eerily orchestrated, too brilliantly written. It’s about as strong a debut single as anyone is likely to have, and that’s because of the darkly morbid kind of intrigue at the heart of it, not in spite of it. But it’s not a bait and switch—it’s just that Bobbie Gentry truly was an entertainer. In fact, she even had her own Las Vegas revue later on in her career, the kind of thing that we might think of as a Plan B but is also reserved only for A-listers.

Bobbie Gentry’s last public performance was in 1982, at age 40, and since then she simply faded away from public life by choice. There have been different reports of her living in different communities in Memphis and Los Angeles, supposedly without her neighbors having any idea of who she was. Fifteen years of being a country star, winning Grammys and Country Music Awards, and this song that hit number one. And then Gentry simply walked away. That’s a mystery in and of itself.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.