Exile From Guyville: Liz Phair and Teenage Daydreams

That summer, Natalie taught me how to love music. They’d pick me up at dusk in their parents’ hatchback to drive around the D.C. suburbs, the moon burning a bright sliver through the windshield. We drove George Washington Parkway for the most part, swooping past Turkey Run, going all the way, some nights, to Mount Vernon. It was a two-lane highway and, thankfully, not crowded after rush hour—both of us were terrible drivers.

While they drove, Natalie would play a CD or plug their phone into the aux cord—a luxury in 2015, and the reason we coveted the hatchback. We listened to Vashti Bunyan, Guided by Voices, Lucinda Williams, and inexplicably, the soundtrack to A Walk on the Moon, a late ’90s film about a bored housewife who has a torrid affair at Woodstock.

That summer, I was fooling around with a boy named Nathan, my hot-but-annoying physics partner with whom I’d maintained a tentative flirtation for most of high school. Nathan didn’t have a driver’s license, which meant I had to pick him up in my parents’ 2005 Toyota minivan—a dose of uncoolness that compromised the coolness I felt sneaking around for the first time in my life. He was tall and handsome and a fantastically bad kisser, which he somehow intimated was a joint failing. I consulted Natalie about whether or not I should have sex with Nathan so I wasn’t a virgin when I went to college.

“Hmm, I don’t know,” they mused, voice impressively neutral. “If the kissing’s bad, I feel like that’s not a good sign for the sex? Maybe think about it for a while.”

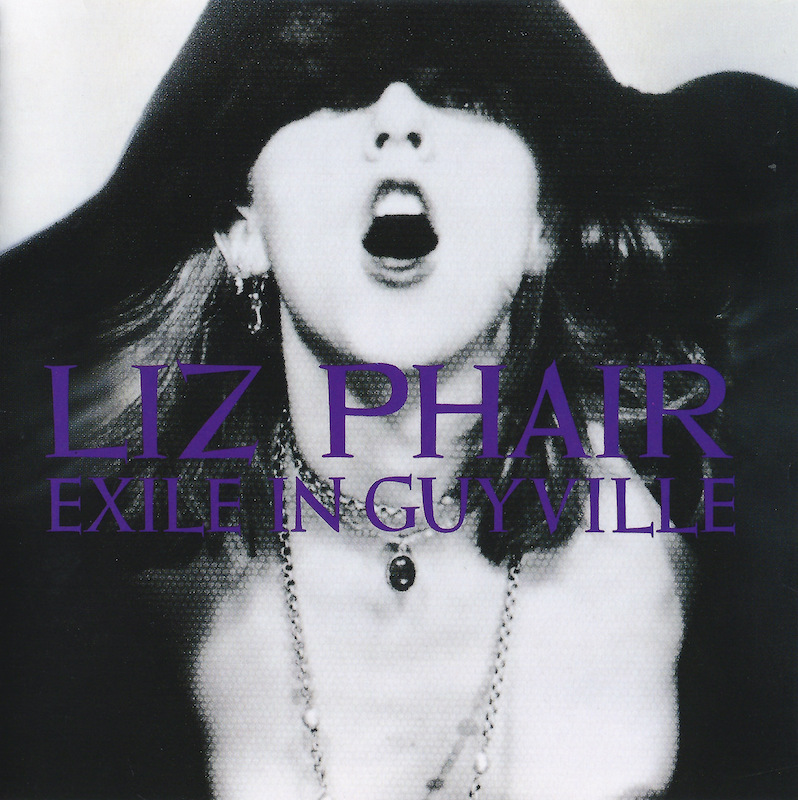

“You’re right,” I sighed, fiddling with the air conditioning vents. Natalie pulled out a CD. “I think you’ll like this one,” they said, and put on Exile in Guyville.

I started falling for Liz Phair the moment the first chords of “6’1”” rang out, and I fell in love completely before the three-minute, six-second song was over, at the moment when Liz launches into the first chorus: “And I keep standing six foot one / instead of five foot two / and I loved my life / and I hated you,” she drones, the guitars and high hat dancing behind her. In that moment, it seemed miraculous there was any woman in the world who was also five-foot-two, like me—a second miracle that she was also annoyed by the handsome, gangly men she didn’t really want to sleep with.

When Natalie played me Exile in Guyville for the first time, my only exposure to rock music was my father’s classic rock records—Pink Floyd, Eagles, The Stones. I hadn’t heard any rock produced after the eighties, and I certainly had never heard a woman fronting a band, growling in a low, monotone voice. In 2015, I did not understand the filthy mix of fear, desire, and self-loathing that coursed through my flesh. My body horrified me; I tried to keep it at a distance. But music, more than any other art form, does not let you forget you have a body. It pulses in the pit of your stomach, dances up your arms, between your flesh and bone.

I liked how Liz sang loud and low, conveying so much emotion in small band of melody. I liked the ghostly, girlish backing vocals. I liked the straightforward, blistering sound of her guitar, the soothing but jarring repetition. I liked how she said the word “cunt,” although I was convinced that something very bad would happen to me if I said it myself.

In those days, I loved the most abrasive, lyrics-forward songs on Exile in Guyville—“6’1”,” “Divorce Song,” and of course “Fuck and Run.” Natalie and I played the record over and over as we zoomed down the George Washington Parkway. “I WANT A BOYFRIEND, I WANT A BOYFRIENDDDD,” we screamed, wind whipping through the cracked car windows. We didn’t want boyfriends, not really. The boyfriends we wanted were fictional, creatures formed entirely apart from the actual teenaged boys who prowled our nights and days.

We were angry. It took us years to learn we were allowed to be angry, and longer still to realize we actually could—that it was possible within our bodies, that we could scream and bite and keen and expel, sometimes, the unrelenting waves of emotions that coursed through us, that we were told were merely pubescent. In 2015, we didn’t know we could be angry. So we let Liz be angry for us, and we sung along.

Those summer nights were special, not least because they rooted my touch-and-go friendship with Natalie. The two of us straddled a funny world at our small public high school, perched between the straight girls who did homework in the library and the DIY kids who smoked cigs in the parking lot. I was usually in the library and Natalie, the parking lot, but the two of us zigged and zagged between the groups. I was cowed by DIY kids, who had sex and did drugs and generally lived their lives in ways that would have forced me to admit I had a body. At the same time, I was aware that if I wanted to have a good conversation about books or music, I’d have to leave the library and find wherever Nat and their friends were hanging out.

The taut, invisible thread between me and Natalie and all the DIY “girls” was that all of us were queer, though most of us didn’t know it yet. The summer of Liz, Natalie and I weren’t just closeted—neither of us thought we were gay at all. In 2015, even our high school—the artsy, public school kids transferred to if they’d been bullied out of the “normal” high schools—had plenty of homophobia. I could count the number of students who were out on my fingers. In the months and years that followed, Natalie’s friends started coming out one by one. “I’m the token straight friend of the group,” Natalie joked one year when we were home from college. Over time, Nat’s friends absorbed me into the fold. Then Natalie came out, and the token, for a while, passed to me.

In December, Exile in Guyville’s thirtieth reunion tour concluded. While Nat and I compared shows we saw 2,000 miles away from each other, I found myself thinking about how the two of us actually left Guyville. Our little queer enclave that began in the parking lot is spread across five states. Our reunions are boisterous—someone has just had top surgery or moved in with their girlfriend or decided to quit their shitty job, or all three. I look around at the life I’ve built as a bi woman and see queer people everywhere—in my phone contacts, community spaces, homecomings. I think back to the years of my life where I found it impossible to imagine feeling safe in my own body, let alone in a public space. I wish younger me could see this life, so far beyond anything she could have imagined.

All of us left Guyville—but the thing that Liz knew, that I now understand, is that you never leave Guyville, even when you haven’t been on a date with a man in years, even when you cultivate a garden of queer friends and lovers around yourself. Guyville exists on the sidewalks and the freeways, in job interviews and restaurants, at the gym, in our living rooms. It swirls around all of us, the largest fishbowl.

I’ve grown to love the quieter tracks on Exile in Guyville—“Shatter,” “Canary,” “Girls! Girls! Girls!” “Shatter” is the longest non-bonus track, clocking in at five minutes and twenty-eight seconds on an album where the standard song length hovers around the three-minute mark. The song opens with a plaintive guitar melody. At times, the melody hits bright notes that move towards resolution, but the sound always dips back into anxious thrums and haunting distortions. The guitar frets yet takes its time. Liz’s vocals don’t come in until over two minutes and thirty seconds into the song. She sings about heartbreak, the kind that cuts over and over again. Her voice stays in a low, tight pitch range until it rises for the first time in the second verse: “I don’t know if I could drive a car/Fast enough to get to where you are/Or wild enough not to miss the boat completely/Honey, I’m thinking maybe/You know, just maybe.”

When I look back on that summer, I sometimes feel grief or anger, but I mostly feel gratitude—for music, and for friendship. These days, Natalie and I live several time zones apart, but their number is one of my first calls when the big news comes, bad and good. Sometimes, I wish I could hold little Amanda and little Natalie: two closeted teenagers trying desperately to understand what it meant to feel in a world which felt so hostile, while everyone around us told us it was normal. I’m grateful for queer spaces and queer friendships, the little oases that keep us joyful and safe for hours, or even moments. When all else fails, we’ve got Liz on CD. We can pop in the disc, roll the windows down, and drive.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.