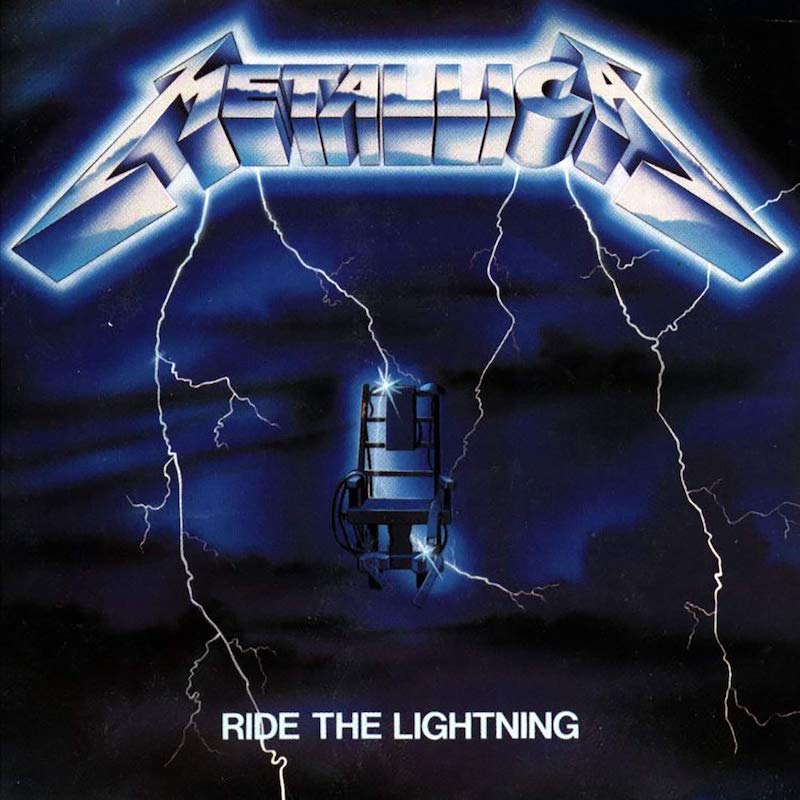

I’ve told this story before, a million times. It cycles through my head like the hero’s journey, the perpetual descent into Avernus, the quest for fire/the grail, the sojourn through death, the return to life. But I’m older now: certain details blur, smear. Was I six when we got the green Circle K basket full of heavy metal CDs? Was I 8? Was it kept in the guest room closet or in my brother’s closet? I can keenly remember it in both rooms, but the ages are all wrong. Reality slowly descends through the murk of fading memory into myth-image alone. Was it even a Circle K basket? Weren’t those red, not green? What remains is that cover: the stark darkness, clouds billowing with wicked intent, a Nietzschean fire, the curl and angularity of the lightning, that fatal chair, and that perfect word emblazoned like the fury of the cross against the sky; METALLICA.

I can’t imagine the shape of my life without Ride the Lightning. I mean this in a non-euphemistic sense. For whatever reason in the curiosity of memory, the key images of my youth feel more often tied to art than events. My first memory, for instance, is me at the age of two, sitting in front of the TV, its knobs useless with the new cable box we’d just had installed, an NES controller in my hand as my brother, age five, was teaching me how to grind for experience in Dragon Warrior by fighting slimes and routinely resting for free at the nearby castle. Neither of us realized there was more to the game; we would grind and grind, for hours, never moving. My second memory: The Legend of Zelda, the superlative sense of wonder I felt at its openness, the way it did away with words (which always, by their nature, affirmed by Derrida and Lacan, fail to cohere to the image we set out to produce), instead hurling me into the thrilling void of adventure. That first Nietzschean bomb burst of raw and eminent Becoming, essence and being defined by action. Ride the Lightning is in this murk. At some point between Zelda and Metallica, there was Power Rangers and Alice in Chains, the late-night childhood insomnia I would later keenly associate both with my dissociative elements of autism as well as the parallel dissociativity of bipolar disorder, both genetic gifts, as I lay awake and wide-eyed at a volume-chilled television playing late night music videos. Have you ever watched the video for “Man in the Box” in early childhood in the most Skinamarink-ass hour of the day, when the stillness of your family half-convinces you they are dead or non-existent? And yet that first thundercrack of heavy metal touched something in me, a dramatic and fiery core, that same autism and bipolar disorder brewing in a child’s heart, unawakened. At last, some blazon rite to make manifest the thunder of my small heart! I would have waking nightmares of the sewn-eye man, a psychopomp, the shadow of the spirit visiting in wickedness at night. But it was a vampire’s hunger; this was the fated thing.

And then in that basket we were gifted by my cousin before he went off to join the Navy, there sat a copy of Ride the Lightning.

(I had heard “Enter Sandman” and the other radio singles of the black album; I was familiar and entranced with their power already; I knew faintly of Master of Puppets and …And Justice For All; I was searching for them specifically I remember; but this was the album I discovered, the album I stole like Prometheus from the wisdom-fires of Olympus rendered physical in my brother’s possessions. It was this album I played in secret on my stereo, eyes closed on the bed, transfixed, transmuted.)

It arrived too early in my life for me to imagine what my life would be without it. It wasn’t a single song; it was every moment, the gestalt. “Fight Fire With Fire” might lay singular claim to my later love of death metal, its intense tremolo riff and half-growled vocal delivery feeling feral and boiling with intensity I didn’t know could exist in music. That the first side follows with “Ride The Lightning” into “For Whom the Bell Tolls” to the side-ending “Fade to Black” is a descent into the pits of death, each song dealing with the terror of death and the abyssal release of life. I was too young to really know what those feelings were when I first heard the record, but I had faint premonitions of what was to come: my step-grandfather had just died, introducing death consciousness into my life and the terrible pondering of the silent pits of eternity, that natural damnation of all that lives; my father’s drinking had begun to tick over from a social and familial annoyance to a real professional hindrance, presaging the precipitous decline he would take; my brother had begun his own Satanic descent into brutal physical and emotional abuse of me, taking out his own impotent anger at the dissolution of the safety of the home on me, the only thing younger and weaker than him. I could sense—fitting—thunderclouds on the horizon. The final solo section of “Fade to Black” rolling overhead like the crackling lightning of the album cover, every element in perfect alignment.

“Trapped Under Ice” and “Escape” feel like a frantic awakening in Hell. The promised silence of the grave stolen from you; in the question of pure animal terror, would you rather death be a cessation of being or the opening of a door of torture? Each answer undoes itself, paints the remaining other as some more terrifying abyss, a hole within a hole, such that it forms an infinite downward spiral. Perhaps then that’s why “Creeping Death” comes next; despite being a story pinched, once again, from films, it feels so much more like Satan laughing over the dead. “The Call of Ktulu” then is the sound of that laughter, cruel, judging. There is an elemental darkness to Ride the Lightning, a sense of intense despair. Perhaps, sure, Master of Puppets might be a better record in some objective sense, especially its title track, which is undeniably the greatest calcification of what Metallica is and what they offer. But I am not interested, in truth, in abstractions like objectivity, which often become dead idols especially of the critic, a curiosity on the shelf as opposed to the arrow that lances the heart. I laid on the bed as a child listening to this record for the first time and its thunderclouds were not figurative but literal for me; I was transformed by their alchemical power. The hunger for art like this woke up, a terrible wolf in the heart. It drove in many ways my lunge toward heavy metal, extreme metal, transgressive art, the unspooling dreamlike qualities of seemingly never-ending prose. The raw imagistic power felt comparable to me then and now to the Bible, to myths, to dream. I wanted that thunder. This was the power I wanted, that sense of perfect and primal Becoming. A child of a broken and difficult home with a broken and difficult mind, I wanted singularly this sense of power and play, like a laughing lion.

There are other places to go to read greater musicological parsing of the record. (That’s an endeavor I think is quite worthy, by the way; the varied influence this record had on metal, both extreme and traditional, underground and mainstream, as well as quietly being a key piece in why modern hardcore sounds the way it does, really can’t be overstated.) One great benefit of this particular venue however is I can write unabashed hagiography, the true image of this record for me divorced from the, at times, frustrating and meaningless rubric of perpetual parsing.

***

I have often been, by nature of my affect, a target of certain kinds of social treatment. Ableism in in two of its forms, first attacking neurodivergence and second attacking mental illness in a form called saneism, are the routine barbs. We have a great deal of social language that masquerades as socially progressive regarding mental illness but at the same time undercuts the firmament of what we mean by disability or illness, that people are fully recognizant under episodes of mania or severe depression or psychosis and so the processes of accountability are identical to sober rational thought, which is precisely the antithesis of what we are discussing when we describe serious episodes. Likewise, autism as a social/psychological disability (not all modes of autism are strictly disabling, but some are) is precisely that social language acts like mores and body language and subtle communication may as well be the eighth color of the rainbow, utterly invisible. Add on the ways in which, despite a growing grasp of gender and queer theory in a general populace, we still often map a simple and vulgar sense of malevolence to those we perceive as empowered and refuse to challenge or complicate these images and we create a complex engine of failed accountability, one that names accountability as process but does not deliver any real satisfying fruits. This is not to say that we are then exempted from social and personal accountability; no one is. Simply that the engine must look very different to produce any gainful results.

This is where Metallica lives for me, and this album in particular. That deathward march of the arc of the record, from fatalism through the threshold of death into the bowels of madness, is one inherently of surrender, a capitulation to storms (again, the image of the thundercloud). There is so much of the world I don’t understand; despite how many words I write, how long my sentences, how big the words I use or abstruse the references to thinkers of philosophical spaces I make, these only occur because I do not understand. The act of reading philosophy and theory, of meditating on my personal life and actions, of being involved in the worlds of politics, are precisely emergent from non-understanding, that I hunger to know because not only do I not know but this not knowing wounds and stings me so constantly. The storms of this record represent in a real and literalized form for me that vastness of the world both inside and outside of me. How sorrowfully, pitifully small I feel.

On paper, this kind of cold confrontation does not seem even possibly joyful or redemptive. But there’s another component at work here, one we often see in transgressive or difficult art: that of truth. There is a fundamental succor to, in simple terms, not being bullshitted. Being told straight what something is. Someday you will die; there is no heaven; capitalism is a brutal machine; on and on. The predicate of the downer in art, of philosophical pessimism, is this sense of direct confrontation. The film The Turin Horse for example was a key work for me in the bowels of suicidal depression; its a story of a man, the carriage driver from the day Nietzsche finally fully lost his mind in Turin and began crying and hugging a whipped carriage horse and crying out to it as the crucified Dionysus manifest, a man raising his horse years later in near total isolation, having lost his wife and driven away his daughter and making no more friends, watching his horse, his only remaining love, slowly die. It is, in short, a crazy fucking downer of a movie. But the fundament of it, again, is that sense of brutal and uncompromising confrontation with truth as well as the intimacy of witness, that even in our deepest pain we can be understood and that understanding itself is a form of love.

Art, it turns out, isn’t just dead aesthetic circuitry but something that happens within the observer, and so the resonances and blistering emotionalities and intellectualisms and experientialities of these genres are also deeply important.

That something like a metal record would stoke these feelings shouldn’t be shocking. Heavy metal, after all, has always operated on the mythic register; this is precisely what elevates it above rock and roll in terms of its form and function. (“Elevate” here not meaning “to better” but “to change”.) People outside of the world of heavy metal might see tough guy machismo posturing and theatrical idiocy; hell, I see it too. And yet these same affects which we see in punk and hip-hop among others are often currently parsed as not really meaning the surface of themselves. The scumbaggery of punk isn’t about being a scumbag per se but about embracing life-as-it-is, finding the joy and jouissance of being, that we are not obligated to be more or less than what we are to be joyful or deserving of love or justice or peace. Likewise hip-hop is correctly seen as a parallel force, speaking more directly to a Black American experience as a means of embracing and challenging being with joy, the image of the rapper or the punk as myth-images and archetypes rather than something that is necessarily real. They are meant to wake some spiritual force up inside of you, to walk tall, believe, love, trust, defend. Take no shit. It’s the same with heavy metal.

Which strikes at another component nested here: Genres as spiritual formations. There is a simplicity we can apply to genres, that they are purely musicological, that an Amen break makes you a jungle producer but a four-on-the-floor with synth pads makes you a house producer. These are useful, obviously, but they likewise are far from the full story; microgenres emerge because on some level, we are attempting as well to talk about the affective character of work. Emo emerged from emotional hardcore, itself just a name for a type of hardcore punk more about emotional turbulence than partying and fighting cops. Death metal isn’t just thrash metal with harsher vocals but a qualitative difference, hence why you can have a thrash record with harsh vocals and blistering double bass and a death metal record with slower tempos and still tell them apart. Likewise, these affective differences aren’t constrained to the music itself either; art, it turns out, isn’t just dead aesthetic circuitry but something that happens within the observer, and so the resonances and blistering emotionalities and intellectualisms and experientialities of these genres are also deeply important. Which is to say: death metal feels a way, techno feels a way, pop and bossa nova and gamelan feel a way.

This is what makes Metallica, especially that magical four-record fun at the beginning of their career and, for me, especially this record holy. And I mean it in that term precisely: the thunder of creation, of witness, of the gaze unto death that reverts back toward life, the primal force that destroys us just as it impels us, the tears of passion confused between joy and sorrow. This is Ride the Lightning. This is the holiest of the holies. For me, this is the greatest record ever made.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.