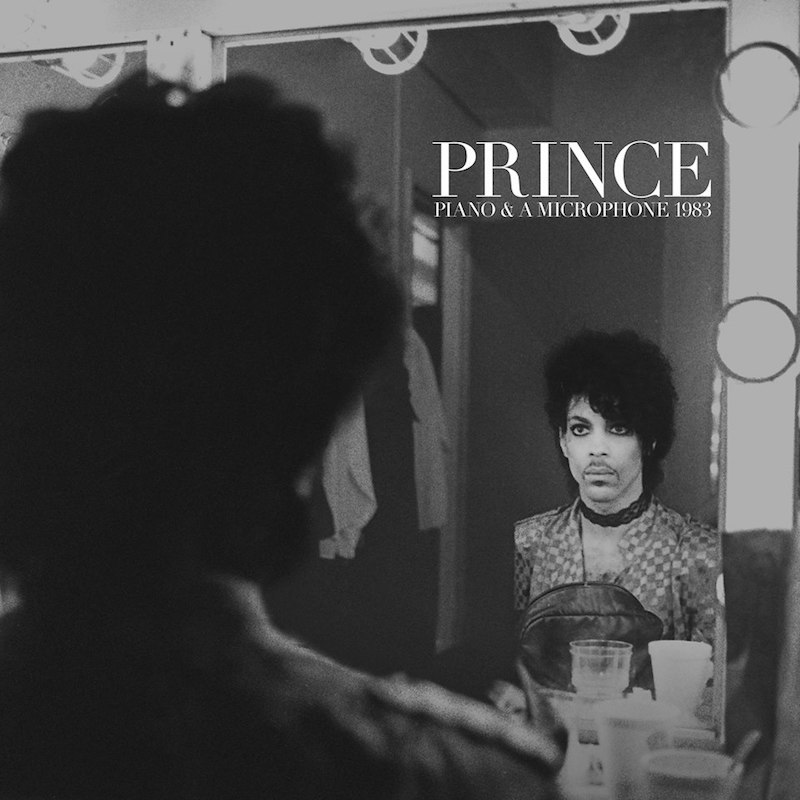

Prince : Piano & A Microphone 1983

The heart wants what the heart wants, and corporate money machines need endless feeding. I get both concepts, I really do. As a music fan and member of Generation X I bore early witness to the shrinking of the timeline for nostalgia to nearly zero, and the search for sources of it to encompass both the sublime and the ridiculous. There’s now a permanent, invisible, constantly shifting border between media releases that pay proper tribute to dormant art and artists, and those that feel like needless cash-grabs.

The year 2016 was a horrifying one in terms of musician deaths, with maybe none so surprising or saddening as that of Prince, seemingly still in the middle of an impossibly fruitful creative life but quietly, ultimately anchored to opiates. After his passing, his family and legal associates cracked open his notoriously private Paisley Park compound and the vaults of unreleased music within. Stunned fans wanted to hear more, to see more, seeking cold comfort from the ghost. People with deep pockets and balance sheets, as usual, would oblige for a price.

I couldn’t have been the only one to see this coming. Hearing his music in something as banal as a credit card commercial was a harbinger of my worst fears about how Prince’s catalog might be manipulated, and the first full posthumous release of his music doesn’t really allay them. The titular premise of Piano & A Microphone: 1983 is thrilling on paper, but what Warner Bros. delivers—and what Prince does as well—is kind of a dud. It’s not necessary or particularly revelatory, especially because it’s already familiar to the hardest of hardcore fans.

Piano & A Microphone: 1983 presents a 35-minute solo piano rehearsal session from Prince’s home studio the year before the release of Purple Rain. Most of the session had already appeared on at least two bootlegs from the 1990s and 2000s (Intimate Moments and Intimate Moments Revisited), held in relatively low regard by fans for their sound quality and the choppy nature of Prince’s improvised tracklist. This release only emphasizes those negatives for a wider audience: classics only teased and unknowns mostly not worth knowing, under a Guided by Voices amount of tape hiss that seems unconscionable for a label and studio with generous resources working on behalf of one of music’s most militant perfectionists.

About half of this mini-LP contains music that rarely if ever appeared again in Prince’s catalog. “Cold Coffee & Cocaine” is a jazz blues number where he affects a vocal squeak that tries to pay homage to both Nina Simone and Ray Charles but does real justice to neither. There are short snippets of “Wednesday,” a song left on the Purple Rain cutting room floor, and of Joni Mitchell’s “A Case of You,” which Prince occasionally covered in concert but wouldn’t officially record until the 21st century.

His falsetto-filled rendition of the spiritual “Mary Don’t You Weep” looks to be the hit single from this set thanks to pre-release streaming and its use in BlacKkKlansman. Yet it’s the hiccuping leftfield dirge “Why the Butterflies”—dramatic pauses, tender vocals, curious keys and chords—that might be the album’s biggest what-if moment. It’s a pairing of earnest sadness and a spare arrangement the likes of which we might pinpoint at few other times throughout Prince’s career. That DNA is suggested in “Nothing Compares 2 U,” but who knows what this specific cut morphed into, if anything.

The rest of Piano & A Microphone: 1983 explores work from the highest peaks of Prince’s early career, with music that appeared around the time of 1999, Purple Rain and Sign ‘O’ the Times. Yet songs like “International Lover” and “Strange Relationship” run fractions of their official album times, suffering from the continuous, medley-style performance occupying most of the space on this release. That session opener “17 Days” (the B-side of “When Doves Cry”) is the only song from Prince’s canon that he fully empowers, while “Purple Rain” can’t crack 90 seconds, helps give the album the sheen of fools’ gold.

This Little Cassette That Could ran out of tape before Prince ran out of ideas, and you can’t really fault him for what’s on here if the ideas weren’t meant for public consumption in a format like this. He pushes his piano and voice to the pop-music limit, cramming multiple styles and feelings grounded in rock, jazz, blues, and gospel into every rendition. We hear Prince making percussive sounds with his mouth and feet, giving his engineer instructions, desperately trying to find a sweet spot for songs to play in front of The Revolution, in front of concert crowds and cameras, in front of his special lady of the moment. Piano & A Microphone: 1983 is genius on display, attempting to figure itself out. But I wonder if recordings from the solo tour he mounted in this fashion mere months prior to his death will see release. That proposes genius on display, all figured out, ready to show out and show off.

What he locked away over his life, yeah, some of it I’m sure he would have leaned on for future commerce given the opportunity. But there had to have been plenty that was for inspiration or experimental value only. And for as much as I love the premise of Prince, his towering talent didn’t prevent him from being a poor editor of his public-facing discography; it’s full of bloat, self-indulgence, and niche interest. With him not here, his living advocates have to make their best (creative? profitable?) guesses at what might satisfy the rest of the world. Piano & A Microphone: 1983 is weirdly low-hanging fruit for them to pick. They need to find a better balance of exploring Prince’s creative process and shining a light on its best results. He deserves that, and so do we.

Similar Albums:

Mavis Staples – Livin’ on a High Note

Mavis Staples – Livin’ on a High Note

Prince – Purple Rain

Prince – Purple Rain

Stevie Wonder – Talking Book

Stevie Wonder – Talking Book

Adam Blyweiss is associate editor of Treble. A graphic designer and design teacher by trade, Adam has written about music since his 1990s college days and been published at MXDWN and e|i magazine. Based in Philadelphia, Adam has also DJ’d for terrestrial and streaming radio from WXPN and WKDU.