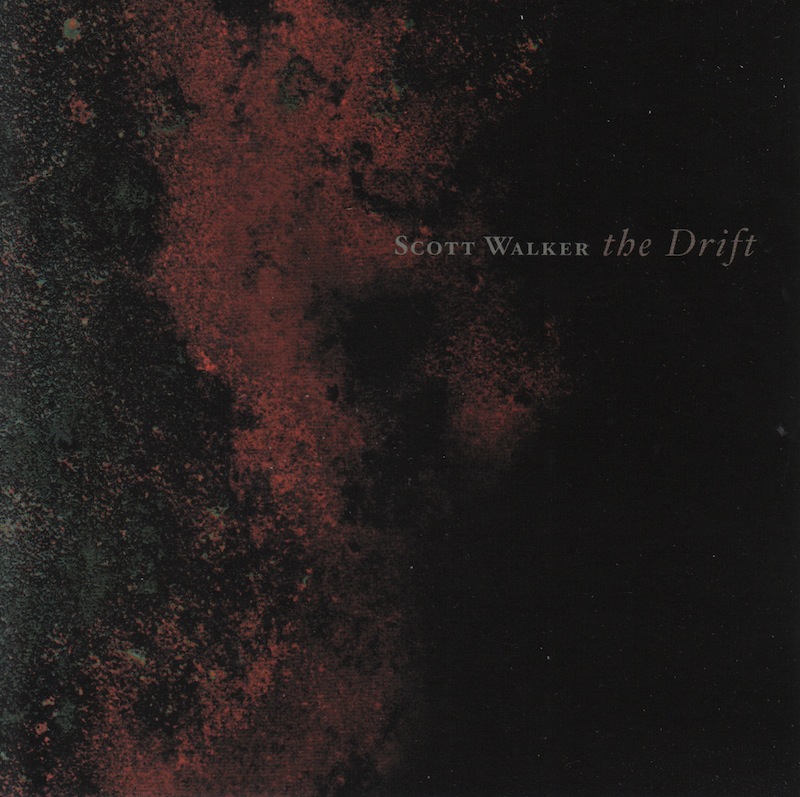

Scott Walker : The Drift

Expatriate. Teen idol. Baroque crooner. Enigmatic recluse. Poet. All of these can be used to describe Scott Walker, once the frontman for the ’60s pop sensations, the Walker Brothers (none of them actually named Walker; Scott’s real last name is Engel), Walker went through some difficult times dealing with stardom and broke off to record his legendary numbered series of four albums in three years. Lately, Scott Walker has seen a huge resurgence in popularity, given the opportunity to curate the Meltdown festival, being hired on by acolyte Jarvis Cocker to produce We Love Life and forever being lauded by the likes of everyone from David Bowie to Radiohead, as will be seen in the upcoming documentary on Walker, 30th Century Man. Songs of Walker’s can also be heard in deleted scenes from Love, Actually, featuring Liam Neeson lipsynching to “Joanna,” and in The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou with “30 Century Man.” Yet, for the past 22 years, Walker has only released three albums. In 1984, he released Climate of Hunter, a fairly experimental affair with a few untitled tracks. In 1995, Walker released Tilt a decidedly more avant-garde album that had critics both scratching their heads and singing its praises at the same time. Now, another eleven years down the road, we are treated to even more challenging, yet rewarding work from Walker in The Drift, an album that can only be readily described as a poetic nightmare set to gothic opera.

The Walker Brothers became famous with the pop song ” The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine (Anymore),” yet that title is probably more apt for the darker landscapes of Walker’s two most recent albums. Backwards recording, sparse, floating and haunting guitars, menacing percussion and macabre orchestration all contribute to the dark, oppressive and foreboding nature of The Drift. This album will likely get more attention for particular tracks due to controversial themes and imagery, much like an aria will get singled out from an opera, but The Drift really needs to be regarded as an entire piece (which is why it is being presented to critics as an album with one long track). “Cossacks Are” opens the album, a possible attack on critics and backhanded compliments Walker might have received over the years from “a noble debut tackling vertiginous demands” to “that’s a swanky suit” and “you could easily picture this in the current top ten,” not to mention the highly backhanded and confusing, “it’s hard to pick the worst moment.” Walker adds backwards recording to signify the confusing praise, while ghostly echo vocals and thumping drums link the words to the subject of the title, likening critics to Cossacks, trampling white roses. “Clara” is even more haunting as Walker recalls an image he saw in a theater of Benito Mussolini and his wife being strung up by the heels and executed. He puts the story, a longtime nightmare of his, into the form of a love song from Benito to his wife, as he pleaded with her to spare herself and escape, yet chooses to die with him. Part operatic crooning and part spoken word poetry, this near thirteen minute creepy wall of noise is beautiful art, and far from what could be considered pop, rock or even some kind of free form jazz. Grisly imagery goes hand in hand with the freeing of a sparrow from a bedroom.

Surely one of the most talked about portions of the piece will be “Jesse,” an imagined conversation between Elvis and his stillborn twin brother Jesse about 9/11. Likening the twin towers to one of the most famous (dead?) celebrities and his long gone twin is ingenious. The World Trade Center towers can be seen as both Elvis, something famous and iconic, yet now gone (or is it?), and as Jesse, a haunting reminder of what could have been, or even as both. Droning guitars represent the planes heading toward the towers while the whispered “Pow! Pow!” in the left, then right channels is the planes hitting the buildings. Walker / Elvis ends the track by repeating, “I’m the only one left alive.” “Jesse” is surely the most poetic and jarring popular art piece about 9/11, making some of the country and rap songs seem pedestrian by comparison. Yet its intent, I’m only guessing, isn’t to make some political statement, but only to make art that reflects life. Things get strange (that is if you don’t think the album is strange already) with “Jolson + Jones,” in which Walker echoes Jolson’s “Sonny Boy” with the sounds of braying donkeys and the shouted phrase, “I’ll punch a donkey in the streets of Galway.“

In “Hand Me Ups,” the central character is somewhat the rewritten character in The Who’s “The Kids are Alright,” willing to give up his progeny for another life, this time for the sake of celebrity. Walker tells us in the press sheet to listen for the sound of an instrument called a Tubax, a saxophone larger than a tuba of which there are only two in known existence. I’m sure Bowie is eating his heart out. Walker mixes imagery of the Balkan conflict and Milosevic to the evolution of the horse as its eyes migrated to the rear of the head to allow for spotting predators as it grazed in “Buzzers.” “The Escape” claims that the world is about to end before leading into Walker alone with an acoustic guitar on “A Lover Loves.” He saves the most intimate part of the album for last, making loud “Psst” sounds into the microphone between lines that suggest an either aging or dead couple, possibly Romeo & Juliet with one trying to wake the other before he ultimately takes his own life, as he sings about “corneas misted” and “one hand that is cold in another colder.“

Now 63 years old, Scott Walker is hoping, as he said in one interview, that listeners find the record “engaging on some level.” With any kind of pop record, like the ones in Walker’s past, radio play and television appearances at least assured some manner of audience. As Walker’s art becomes more challenging, poetic and radical, albums like Tilt and The Drift find fewer outlets from which to be heard. Maybe this is why those in the spotlight, such as Bowie, Radiohead and Pulp, are championing his work. The term ‘pop idol’ is so far removed from what Walker is now that it becomes difficult to reconcile the two. Instead, Walker is an artist, using poetry and avant-garde music to express fears in our time, nightmarish images of the past and the dark omnipresent future. Catching Walker’s Drift is both equally rewarding and terrifying, like Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” set to music.

Similar Albums: