Sonic Youth carved their path to becoming the quintessential band of the American underground on the very thing their name projects: Sound. From their early no wave recordings on deeper into the ’80s, Sonic Youth found inspiration not just in songwriting but in manipulating their instruments to warp and bend in ways not intended by manufacturer specifications, whether through homemade modifications, unusual tunings or playing them with implements other than a pick. Which might not have been half as effective had they not also written great songs, they just weren’t great songs that sounded like anyone else’s.

Sound was their medium, but every artist likewise has a subject, and for Sonic Youth that often shifted, from abstract variations on songs of love and lust to actual pop cultural critique. But for much of their career, particularly during an intensely productive period in the mid-1980s, Sonic Youth’s songs displayed a particular doomed fascination with the ideas of America that reached dubiously mythical status in the Reagan years. As the group’s atypically constructed noise rock anthems found a nationwide audience through regular touring and increased presence on college radio, Sonic Youth entered a creative streak that produced three albums that represent a masterful trilogy of albums informed by the myth of America as well as being haunted by its shadow: Bad Moon Rising, EVOL and Sister.

A kind of woozy, amorphous darkness pervaded Sonic Youth’s music from the mutant dissonance of their earliest no wave recordings, but on Bad Moon Rising that darkness began to take on a more defined shape. The album shares a title with a ubiquitous entry in the classic rock canon by Creedence Clearwater Revival, both suggesting something quintessentially American while evoking the impending doom of apocalypse. Its cover art, likewise, depicts a similar intersection of ominous Americana, the Jack-O-lantern head of a scarecrow burning bright in front of a cityscape, which only looks out of place if you don’t imagine the metropolis in the background descending into dystopia.

Where 1983’s Confusion is Sex thrived on a kind of stylized atonality, the songs on Bad Moon Rising were just that, not always entirely congealed from the eerie mist whence they came, but taking on a hypnotic form all the same. The groove in a track like opener “Brave Men Run (In My Family)” is undeniable even if it’s not so overtly catchy, though the off-kilter tonal quality it harbors, as does much of the album, lends it an unsettling quality that shadows the burning pumpkin head and its suggestion of a coming endtimes.

Implied though that apocalypse might be, it’s uniquely American, from the atrocities committed in the name of colonization (“They gave birth to my bastard kin,” Kim Gordon chants in “Ghost Bitch,” “America it is called“) to the sensationalism of the Manson family cult murders in “Death Valley ’69.” “Death Valley,” still deeply unnerving more than 35 years later, paired Sonic Youth’s first proper college radio-ready single with what remains their most nightmarish imagery. It opens with a blood-curdling scream and descends deeper into Hell, Thurston Moore and Lydia Lunch depicting a gradually unfolding scene of violence (“I didn’t wanna, but she started to holler, so I had to hit it“) as the tension in the music grows precarious close to climactic collapse. It’s harrowing; it’s exquisite.

Moments of abrasion disrupt otherwise more immediate pop songs in much the same way the band’s evocations of chaos and infamy emerge alongside images of celebrity and glamour.

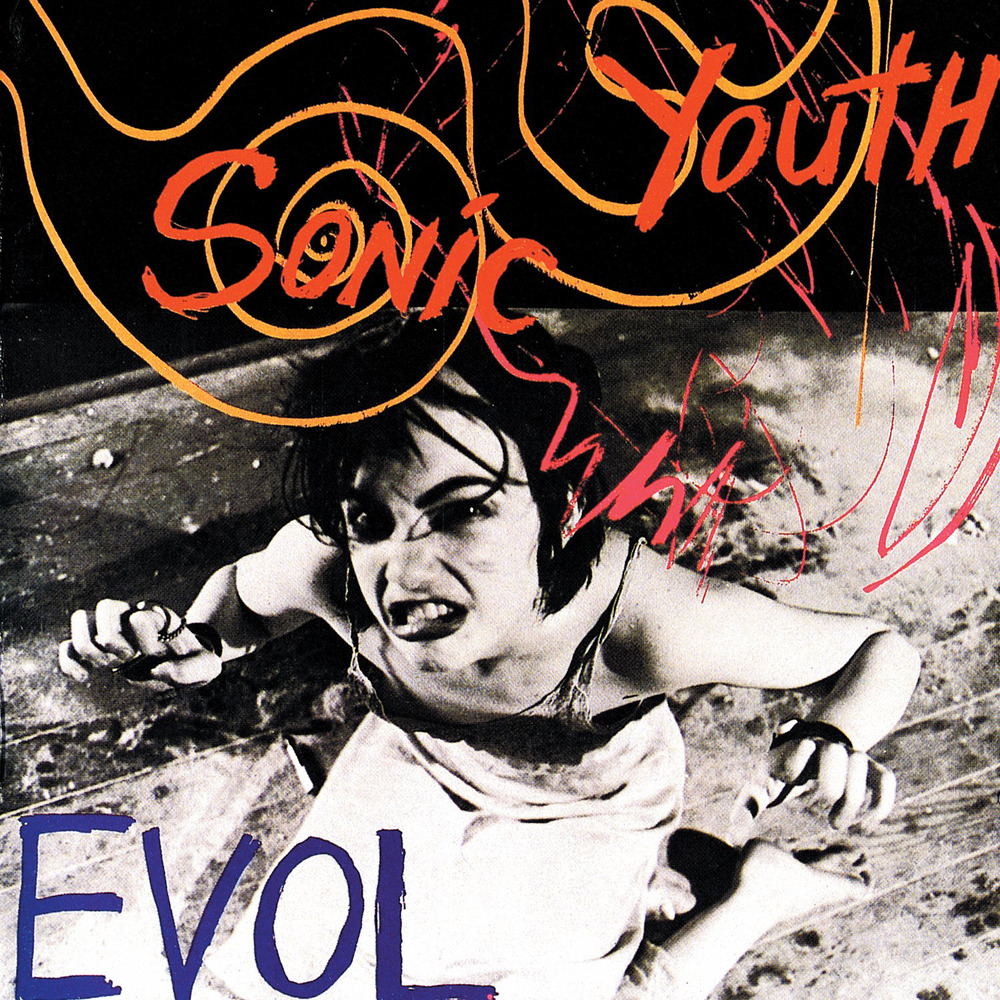

The release of 1986’s EVOL signaled the completion of Sonic Youth’s evolution from mutant atonalists into the pioneering noise rock group that eventually released the game-changing Daydream Nation. Two notable events coincided with this arrival; the first, drummer Steve Shelley became a permanent member of the group, replacing Bob Bert and remaining the urgent, versatile backbone of the band up until their breakup in 2011. And second, it was the band’s first release for iconic California punk label SST, signaling both Sonic Youth’s escalation toward greater visibility while the label itself was moving farther away from its hardcore punk roots. The partnership didn’t last very long—as was the case with many famous SST-affiliated artists—but it yielded two of their best albums, EVOL included.

Sonic Youth understood the language of pop but, during the first half of the ’80s at least, rarely chose to speak it. That changed in large part with EVOL, which boasted at least one bonafide pop song, “Starpower,” at least a pop song created in their own image. Both dissonant and disorienting yet brimming with hooks, “Starpower” seems like a contradiction on its face, but it’s more aligned with the driving post-punk singles of the early ’80s than what Sonic Youth were creating just a few years before. What’s more, it’s a love song, or at least a depiction of infatuation. “Spinning dreams with angel wings, torn blue jeans, a foolish grin,” Kim Gordon sings, her delivery evoking detached cool even in describing a moment of ecstasy.

There’s a different kind of star power on album closer “Madonna, Sean and Me,” or at least the suggestion of it, one of many references to Madonna—a frequent subject of fascination for Sonic Youth—that would show up throughout their career, culminating in the release of the experimetal-but-fun one-off Ciccone Youth album in 1988, featuring covers of both “Burning Up” and “Into the Groove.” Both Madonna and Sonic Youth had risen up from the same New York underground scene in the early ’80s, and performed at the same clubs—the band had even sent Ciccone Youth’s The Whitey Album to Madonna’s sister to earn her blessing, which she graciously gave them. But “Madonna, Sean and Me” isn’t about Madonna any more than opener “Tom Violence” is strictly about Tom Verlaine (or violence), its droning noise-rock freakout and ominous lyrics sharing more in common with the Manson family visions of Bad Moon Rising standout “Death Valley ’69,” opening with Moore’s portentous threat, “We’re gonna kill the California girls.” It ends in a locked groove repeating the notes F# and A, just a half-step away from the infinite loop as noted (and very likely influenced by this brief snippet of music) on Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s debut LP.

Elsewhere Lee Ranaldo offers dark visions of highway violence on “In the Kingdom #19,” his recitations of lines like “Still out ghosting the road/Death on the highway” take on an eerier quality in the aftermath of the death of The Minutemen’s D. Boon in a van accident the year prior. It, incidentally, features the first recorded music from the band’s Mike Watt since Boon’s death, in addition to the sound of actual firecracker explosions happening inside the studio, lending even more chaos and terror to the tense, spoken-word track. And “Shadow of a Doubt” nods to another American icon, Alfred Hitchcock, referencing two of his films, the titular Shadow of a Doubt and Strangers on a Train.

Where Sonic Youth waded into pop on EVOL, they fully dive in on Sister, embracing accessibility without leaving behind the darkness or abstraction that defined their material up to that point. Simply put, Sister remains a very weird album, but it’s a weird album that’s driven by more overt melodies than those that precede it. Even its most urgent moments, like “Tuff Gnarl” or “Pipeline/Kill Time,” still descend into middle sections of scrape and drone. Moments of abrasion disrupt otherwise more immediate pop songs in much the same way the band’s evocations of chaos and infamy emerge alongside images of celebrity and glamour.

Pop culture by and large informs Sister as much as actual pop music, particularly the science fiction of Philip K. Dick—the sister referenced in the title is Dick’s fraternal twin, who died shortly after being born and which left a heavy impression on the writer that followed him throughout his life. The author’s influence appears in songs like “Stereo Sanctity,” where Moore references Dick’s novel Valis with “Satellites flashing down Orchard and Delancey” and how “I can’t get laid because everyone is dead.” The connection to his sister arises in “Schizophrenia,” which is intertwined with Gordon’s relationship with her own brother, who was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. But the insidious influence of American pop culture shows up more subtly in other places, the original release of the album featuring an image of Disney’s Magic Kingdom that was later covered up due to unauthorized use.

Sister is also, by and large, a remarkably beautiful album by the standards of a band that emerged from a kind of loosely organized noise. The hazy “Beauty Lies in the Eye” is gorgeous in its melancholy, but obscured and distant, dripping with mystique. And for the first time on any Sonic Youth album, Moore and Gordon can be heard singing together in harmony (sort of) against an unsteady squall on “Cotton Crown,” its narcotic romance still carrying a strange sort of sweetness as they sing, “Angels are dreaming of you.” Even amid the sublime moments and the driving, rhythmic post-punk that define Sister as one of Sonic Youth’s most focused and simply best albums, the terror of the fringe menace of Bad Moon Rising still simmers under the surface, bubbling up to a boil on the abrasive grind of “Pacific Coast Highway” as Gordon chants, “Come on get in the car, let’s go for a ride somewhere/I won’t hurt you, as much as you hurt me.” Though Sister is as much about a kind of intoxicated dreaminess as much as it is an imagining of a potentially broken future—an American hallucination as much as an American dream—violence somehow still feels inescapable.

If Sister isn’t regarded as Sonic Youth’s finest moment—the place where each disparate part connects and the group’s yen for dissonance finds a suitable companion in rhythmic drive and immediacy—it’s only because Daydream Nation showed up one year later. From the epic opening anthem “Teen Age Riot,” they signaled a step toward brighter frontiers, with the bloodthirsty cults, junkie couples and flashy Disney and MTV figures fading to a blur in the background as Sonic Youth became icons themselves. Moving away from the reflections of the flawed and sometimes harsh America as it was, they imagined an entirely new one, guided by President J Mascis to unite the youth under a new platform of freedom and noise.

Note: When you buy something through our affiliate links, Treble receives a commission. All albums we cover are chosen by our editors and contributors.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.