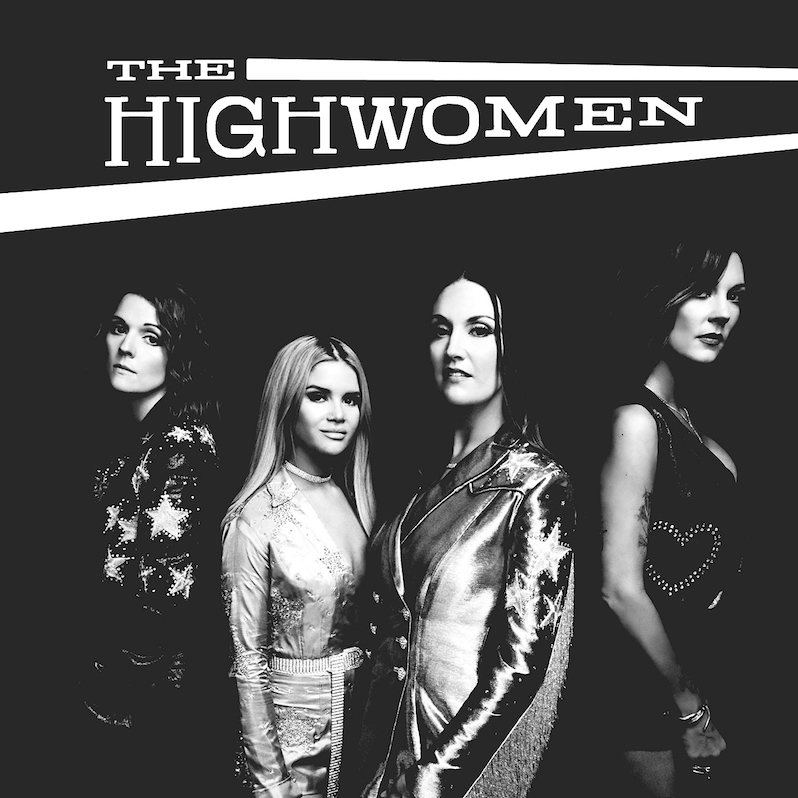

The Highwomen : The Highwomen

The eponymous opening track of The Highwomen’s eponymous debut album is so arresting and deeply moving as to set standards almost impossibly high for the rest of the record. But while The Highwomen possesses a tone that is uneven and occasionally verges into the downright hamfisted, “Highwomen” and the other high points on this album by country luminaries Brandi Carlile, Maren Morris, Amanda Shires and Natalie Hemby have such intensity and purpose that it’s hard to view the work as anything other than, ultimately, a net positive for country music.

Let’s return for the moment to that title track, with which I am, to be honest, somewhat obsessed: Over a version of the melody from “Highwayman”—theme song for the Cash/Jennings/Kristofferson/Nelson country supergroup from which this quartet adapts its name—it presents anecdotes from a Honduran immigrant, a pagan mistaken for a witch, a Freedom Rider and a rebellious priest. All of them die for their beliefs but profess (as the original Highwaymen did) that they are still alive in the hearts of those they inspired. “Highwomen” seems to reach its peak of poignancy during the Freedom Rider verse (sung by guest singer-songwriter Yola, a titanically talented rising star in her own right who, lest anyone be justifiably concerned with co-opted narratives, is Black). Then it hits you with the following harmonized gut punch: “We are the daughters of the silent generations/You send our hearts to die alone in foreign nations/And they return to us as tiny drops of rain, but we will still remain.”

Whether this song or the other more pointed tunes on The Highwomen will make it to mainstream country charts remains to be seen, but it’s worth noting that Elektra presented it as a single. The label machine is not being coy about the group’s politics or message of empowering women in a genre that often pigeonholes them. For some of this site’s readers, the most visible country stars are women (Kacey Musgraves, pre-pop-move Taylor Swift, Miranda Lambert, maybe Ashley Monroe) due to their acceptance outside the Nashville bubble, but comprehensive data proves that they are outliers, struggling for purchase in a sea of male artists who often steer gleefully into every shitkicking cliche of what the menfolk’re s’posed to act like in country songs. No corner of the music industry is untainted, but corporate Nashville is a reeeaaaallllllll bad place.

I can imagine some folks might wonder at this point if I’m trying to posit The Highwomen as some sort of faultless miracle. I am not. The album’s uneven tone is first presented on track two with the enjoyable but arguably counterproductive “Redesigning Women”—it is just a weird flex to pivot from the righteousness of “Highwomen” to cliches about women buying a shitload of shoes and dyeing their hair a lot. There is precisely zero wrong in a vacuum with women (or anyone else) buying a shitload of shoes or dyeing their hair, it just seemed off-putting in sequence. Perhaps more to the point, “Redesigning” is simply nowhere near as good as most of this album’s songs.

Other parts of the album that embrace humor are much more successful. “My Name Can’t Be Mama” is a sentiment any young parent can appreciate, in which Carlile, Morris and Shires attempt to juggle parental responsibilities with adult problems both micro (a hangover) and macro (life as a touring musician). “Don’t Call Me” is a hysterical kiss-off that ends with Shires talk-singing “1-800-Go-To-Hell” in the direction of a melodramatic ex. And in “If She Ever Leaves Me,” a song that’ll probably get as much attention as “Highwomen,” Carlile mocks a cowboy wannabe for wearing too much cologne while they compete for the attention of a singularly beautiful woman. The true impact of Carlile’s tune is not in her own sexuality (she’s been out for almost 20 years), but that it looks at a slice of LBGTQ+ life as simply being another part of humanity’s tapestry, rather than something wildly out of the ordinary.

That is perhaps the most substantial message of The Highwomen: Inclusion requires some reorientation at times, but it doesn’t have to be hard work, due to its very principle that everyone has merit. “Crowded Table” makes this point most directly, first in an absolutely gorgeous four-part-harmony hook—“I want a house with a crowded table/And a place by the fire for everyone”—and later in a climactic bridge: “Everyone’s a little broken, and everyone belongs.”

Similar lines are all over The Highwomen, so earnest that they may provoke skepticism from the jaded. Sometimes they just plain don’t work as well as they should, and conversely, a few of the album’s best tracks work so well because they zero in on the personal so deeply and eschew sociopolitics (“Loose Change,” “My Only Child”). But the album’s willingness to stand for decency at the risk of sounding corny is welcome—especially by comparison to the slick faux-joy that dominates modern country—and its message lands successfully more often than not. This is easily one of the best country releases of the year.

Similar Albums:

Kacey Musgraves – Golden Hour

Kacey Musgraves – Golden Hour

Nikki Lane – Highway Queen

Nikki Lane – Highway Queen

Sturgill Simpson – A Sailor’s Guide to Earth

Sturgill Simpson – A Sailor’s Guide to Earth