Tracing the complicated roots of “alt-country”

Following the pattern established by the first two chapters of this column in which I’ve examined certain aspects of country music side by side with how I came to know them, the next step chronologically must be alt-country—“whatever that is,” as No Depression (the magazine) once termed it.

The label “alt-country” is a loaded one, which requires considerable unpacking because of how it has sometimes been touted as a superior alternative to its progenitor. Plenty of great music exists under its umbrella. Some of it is, effectively, classic country wearing a different hat, while other examples are much more out there.

***

Do a cursory web search and you’ll find multiple assertions that Uncle Tupelo is the first alt-country band, and their debut No Depression the genre’s first album. This is only true in the sense that the term emerged alongside the band. It’s otherwise fucking ludicrous. It can be easily disproved with research that goes even a bit beyond the cursory, but received wisdom has a way of being persistent. There has been country music that, despite mostly fitting firmly into the genre’s general parameters, defied convention in various ways, since at least the 1950s.

You can make the argument that, in addition to being one of the epicenters of rock ‘n’ roll, Sun Records also begat a more outside-the-box iteration of country. Elvis Presley’s cut of Bill Monroe’s “Blue Moon of Kentucky” comes to mind, of course—and if I want to get nuts (I often do), I might suggest “That’s All Right” (1954) and “Mystery Train” (1955) also belong under this umbrella. The latter two are often spoken of as either appreciation for or highway robbery of the blues, depending on who you ask (the truest answer is “it’s both”), but they’ve also always felt country to me, particularly “Train.” Considered in a historical context, they’re revolutionary, yet the instrumentation is fragmentary compared to the honky-tonk of that time being played by stars like Lefty Frizzell, Webb Pierce and Eddy Arnold. The same is true of the earliest Johnny Cash & the Tennessee Two singles (“Hey Porter” and “Cry! Cry! Cry!”, both 1955). Carl Perkins had a similar template but sped things up to the tempo we commonly associate with rockabilly on “Blue Suede Shoes/Honey Don’t,” assisted in no small part by the thunderous (for 1955) drums of Fluke Holland. For the next several years, rock ‘n’ roll/rockabilly/whatever you want to call it effectively killed country music, a feat that alt-country could’ve never accomplished in the 90s (and certainly—inasmuch as the subgenre even exists now—won’t accomplish today).

Country re-established its cultural standing not by attempting to emulate rock, but instead pivoting into pop with the ornate, string-laden, backup-singer-bejeweled production style of Owen Bradley: the Nashville Sound. That reigned supreme for much of the decade. But it’s not as if country with raw power didn’t exist and even thrive during this period. Some of it had Nashville Sound all over it, some was more stripped down.

Consider a song like “Night Life.” Now understood as a country standard, it didn’t reach a large audience until three years after Willie Nelson wrote and sold it, as the centerpiece of Ray Price’s 1963 magnum opus of the same name. Nelson recalled in his first autobiography that Nashville producer/pseudo-Svengali Pappy Daily didn’t think it was country. Again, this even being a notion will sound absurd to modern ears; the guitars going full blues in isolated moments (a stylistic choice Price retained on his version) don’t change the fact that the aching “Night Life” is as country as it gets. Daily’s skepticism is just another example of how Nashville always reacts initially to things outside of whatever its established norm is at any given time. It took a chart-topping juggernaut like Price—an intermittent iconoclast himself, despite his not-infrequent employment of the Nashville Sound—to send “Night Life” into the canon of country’s best songs, where it belongs. It is austere and beautiful, a dispatch from somewhere lonelier than “Lonely Street” (where Price also went on that LP). It lives in the places that, before then, only Hank and George and Patsy seemed equipped to explore. Price used his voice as a searchlight to survey the ground Willie Nelson had mapped out.

Nelson was an equation that Nashville’s establishment couldn’t solve long before he turned “outlaw.” The phrasing, the jazz-influenced guitar he threw into the mix whenever he could, the complexity of his writing—pick a card, any card. Producers could drown songs like “Half a Man,” “The Party’s Over” and “Permanently Lonely” in as many overdubbed string arrangements and Anita Kerr Singers/Jordanaires shit as they wanted; the quality of the tunes shines through no matter what. Nelson’s best work, triumphs like Shotgun Willie, Phases & Stages, Red-Headed Stranger came with studio independence in the ’70s, and paved the way for experiments like Spirit and Teatro in the ’90s. But the idiosyncrasies that define those records are embryonically present on his 1960s releases. Another future outlaw, Johnny Paycheck, arguably made more interesting and emotionally resonant country music in the ’60s, on the pissant Little Darlin’ label, than he ever did at Epic. This is in no small part because the things that made Paycheck stand out on singles like “A-11” and “Heartbreak, Tennessee” had nothing to do with instrumentation or image—most of which was fabricated by producer Billy Sherill—and everything to do with the expressiveness of his voice. Moreover, when Paycheck first truly became an “outlaw,” it was due to (CW: sexual assault) an unspeakable crime. For which he received barely a wrist-slap as punishment.

All of this is to say that country music has always had square pegs that didn’t fit into round holes, whether it was advertised as such or not.

***

I have a knack for being drawn to troubled artists, across all mediums. I would say I have it to a greater degree than the average person. I’m not the least bit proud of this; it’s a source of great shame.

Because of my inability to understand my own psyche, a vast misunderstanding of what it meant to be a creative person and a grand old heaping of masculine stupidity, listening to certain musicians helped reinforce the idea that you needed to have some mental torment to craft meaningful writing, music or whatever else. This is, of course, patently bullshit, but trying telling that to a 19-year-old male hearing, God help me, Ryan Adams’ Heartbreaker for the first time. I wish I could erase that from my head, but I cannot. In fairness, plenty of the musicians and bands I’ve discussed, and will discuss in future installments, have written or sung more mean-spirited songs than “Come Pick Me Up” or done worse things than (CW: sexual harassment/assault) what Adams allegedly did. A significant number of those people are also dead, and thus listening to their music cannot possibly be considered a present-tense endorsement of any bad behavior they exhibited.

Country, both of the “alt” and “original recipe” varieties (if we are to briefly entertain this questionable dichotomy), is full of artists that encourage this tortured-artist idea. Making a list of all examples of such would be pointless. Many did so without being conscious of it at all, while some played it up a bit without fully understanding the implications. I’m old enough now to understand all that, and also to know that you can listen to and appreciate that sort of stuff without internalizing it. As a younger man, I deeply romanticized being a tortured artist to such a degree that, in conjunction with other much deeper flaws unique to me, doing so genuinely affected me for the worse. It was an exacerbating factor, not the cause—I am not remotely stupid or irresponsible enough to say otherwise—but however it happened, it happened.

***

Just about everything you hear in country is also present in the best examples of what is commonly referred to as alt-country—the twang, the heartache, the evocation of detailed places, the combination of Black blues and Appalachian folk underpinning it all. As Roy Acuff allegedly said, after beseeching the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band to describe the sound of the now-legendary album that shares a title with this column and finding their descriptions wanting, “It ain’t nothin’ but country.” A more egalitarian but similar statement is quite famously voiced by Kris Kristofferson at the start of his original (and superior; fucking fight me) version of “Me and Bobby McGee:” “If it sounds country, man, that’s what it is….it’s a country song.” Alt-country wasn’t a cynically manufactured term per se, in part because the sound didn’t ever catch on enough to put dollar signs in record executives’ eyes. (It’s hardly even a term that’s used today, having been supplanted by “Americana,” the background and etymology of which is a whole other can of worms that we’ll likely address in another chapter.)

“Outlaw country,” one of alt-country’s clearest antecedents as a genre, was effectively a cynically manufactured term, even though the music it described was anything but synthetic: The casual music-listening public learned it from a cash-grab compilation put together in 1976 by RCA executives sulking that Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings were enjoying massive critical and commercial success without conceding to said executives’ horseshit. (Hazel Smith claimed in Ken Burns’ Country Music documentary that she invented the term, and maybe she did, but that’s not where/from whom most people heard it.) Nelson, Jennings, Jessi Colter, Tompall Glaser, Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, David Allan Coe, Billy Joe Shaver and Steve Earle are just a handful of the artists lumped into this category, and, as with the alt-country artists they’d eventually inspire…a lot of what they made sure sounds like country to me. In the best possible way! But back then, “country” had grown to be shorthand for “Nashville string-section bullshit,” the same way it is now synonymous for many people with, uh, whatever fucking Dan + Shay are supposed to be. So you can understand fans’ desire to separate Willie and company from the Nashville pack.

I feel the same about most of the 1980s music categorized as cowpunk: In 2021, hearing bands like The Long Ryders and Lone Justice—especially the latter, whose music I loved within 30 seconds of hearing “Ways to be Wicked” — all I’m thinking is, “That’s country! How is that not country?!” Fast forward to the early 1990s, and you get Uncle Tupelo, whose music is sometimes country, sometimes “Replacements with far fewer jokes and a lot of twang.” That definition can also apply to The Jayhawks (though they have some jokes), Son Volt (zero jokes, and also boring), Old 97s (pretty solid, beaucoup humor) and Lucero (just awesome, one of the most consistent bands of any kind), to name just a few. Wilco played briefly in this sandbox (on A.M. and Being There) before moving on to more adventurous territory. Then you have artists like Alejandro Escovedo, Old Crow Medicine Show. Lucinda Williams and Gillian Welch, who sit much closer to straight-up country. The alt-country umbrella covers far more artists than those I’ve named here, of course, but all of them are decent starting points. (I’ve also said more than a few times that this column will never claim to be any sort of definitive history of any genre or subgenre.)

And then there’s Whiskeytown, often thought of as nothing more than Fucking Ryan Adams’s first band. Which kinda sucks, because he wasn’t the only member of that band: Caitlin Cary not played some of the more interesting country fiddle you’ll hear (outside of stuff by true legends of the instrument, like Buddy Spicher) on Faithless Street. She also sings lead on the incredible “Matrimony,” a song few people will hear because…as stated. Phil Wandscher can’t really sing that well, but “What May Seem Like Love” and “Top Dollar” are fun, ramshackle numbers. Check all of those out, if nothing else.

I’ve belabored the point all but to death by now, but once again: All of this is country unless otherwise classified per caveats above.

***

There is some stuff on the outer limits of country that’s capable of taking you places you don’t often go in other music of any genre.

Starting with the hallucinatory twangy freakout of Fear and Whiskey, Mekons have spent nearly four decades making fascinating and provocative music informed by country but not really within it, with a sound as much a parallel to Public Image Ltd. and Wire as it is in debt to Buck Owens or the Tennessee Two. The short-lived Geraldine Fibbers, featuring future Wilco guitarist/inexhaustible session man Nels Cline, made two intriguing albums that are fascinating hybrids of country-rock and Slint. (Slint are effectively their own genre at this point, no?) Calexico, on albums like the outstanding Feast of Wire and Carried to Dust, blend country sounds with Tejano, norteño, cumbia and electric blues. And while I made the argument in our last chapter that the “gothic country” bands were, essentially, just as country as Waylon Jennings, I also cannot deny that a group like 16 Horsepower was possessed by a darkness beyond what is typically seen in even the darker corners of country and much more akin to, say, the doom folk of Chelsea Wolfe. (Then again, would you even have doom folk without country music? Unclear!)

Again, these are just a handful of bands. Going on further would begin to make me feel like this section were something adjacent to list-making. That seems tedious.

Perhaps no one sums up the sort of true otherness and fascinating artistry that can sometimes exist in country music better than Terry Allen. How exactly to categorize something as buckwild as Juarez, Allen’s 1975 concept album about murder, love affairs, the imperialist conquests of Central and North America, Mexican beer and approximately 86,712,851 other things? Despite his relative geographic proximity, as a Lubbock-born Texan, to artists like Willie Nelson and Guy Clark, he was not often part of the country scene (though Clark was a close friend), and did nearly as much (arguably more) work as a visual artist and sculptor as he did in the musical realm.

The music he did make, however, is fascinating beyond belief. Juarez’s sound is defined by Allen’s piano — an instrument not always thought of as country by surface observers despite being fundamental to the genre (as Owen Bradley, Floyd Cramer and Pig Robbins would readily tell you if they could). It’s simple, almost austere playing, not that far removed from something you can imagine was banged out in the earliest honky-tonks. Mandolin and guitar appear intermittently to fill out the edges. Allen is, to put it mildly, not the most accomplished vocalist, but what he does works in the context of the rough-hewn, violent story he’s telling. Later albums like Lubbock (On Everything), Bloodlines and Human Remains would have a much fuller sound and stick closer to fundamentals of country songwriting, and they are every bit as interesting despite being more “conventional” than Juarez. Moreover, as recently as 2020, he was releasing shit as bizarre as Just Like Moby Dick, an album about subject matter ranging from vampires and strippers to forever wars. Anyone who, despite countless evidence to the contrary, still thinks they will be bored by country music should immediately delve into Allen’s rich back catalog.

***

There are some listening experiences I’ll never forget, and at times attempt to recreate even though doing so is, by nature, impossible. This requires backtracking somewhat in the rough chronology I’ve established throughout this column, but fuck it.

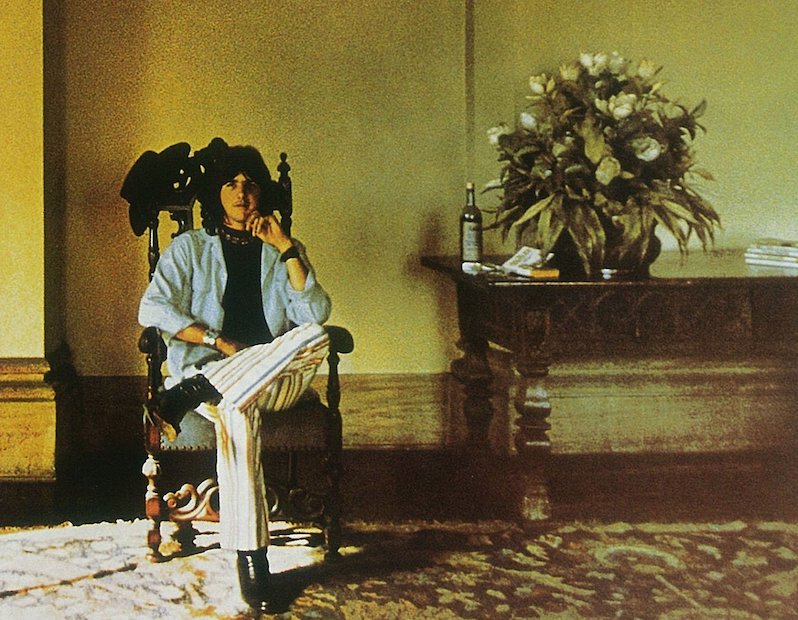

I must’ve been 17. I had unearthed my parents’ vinyl collection. Lots of Bob Dylan, lots of Stones, plenty of folk—and Gram Parsons’ Grievous Angel. With the Bright Eyes album I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning having piqued my interest in, well, “country by artists not named Johnny Cash,” and Conor Oberst having been compared to Parsons (and enlisted Emmylou Harris for harmony vocals on three of that album’s songs), I figured I had to give it a spin.

Memory doesn’t permit me from recalling how I reacted to all of these songs. I can remember being hit pretty hard by the moment in “Return of the Grievous Angel” when Parsons and Harris sing “And I saw my devil, and I saw my deep blue sea.” Something about Harris’ voice on that line just cuts right into you. I definitely remember wry amusement at “I Can’t Dance,” because I fucking could not dance and never really have been able to, just like Gram sings.

Eventually I got to “Love Hurts.” I know for sure I cried. Not bawling because I didn’t open my mouth, but the sort of quiet and intense weeping that brings pain to your facial muscles and your throat. Their take on the Boudleax Bryant-penned standard, while not a duet in the classic sense, is nonetheless one of the best country duets of all time. Up there with anything George Jones did with Tammy Wynette or Melba Montgomery (e.g., “Golden Ring” or “We Must’ve Been Out of Our Minds,” respectively). On the level with anything by Loretta Lynn and Conway Twitty. Up there with “Jackson” by Johnny and June. Without Parsons and his cosmic American music, alt-country likely would not exist, nor would much of the best “traditional” country of the mid-1970s and beyond. Nor would a whole lot of other music in numerous other genres. (Now, as far as tortured artists go, I would’ve been a lot better off getting seriously into Parsons rather than, well, you know who, but because I lack a time machine, it is what it is.)

My main hope for this column is that it leads even just a few of you to discovering a country artist or song in an experience as intense and fulfilling as what happened to me with “Love Hurts.” This genre is multifaceted, complicated and often frustrating, but when it hits, man if it isn’t beautiful.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.