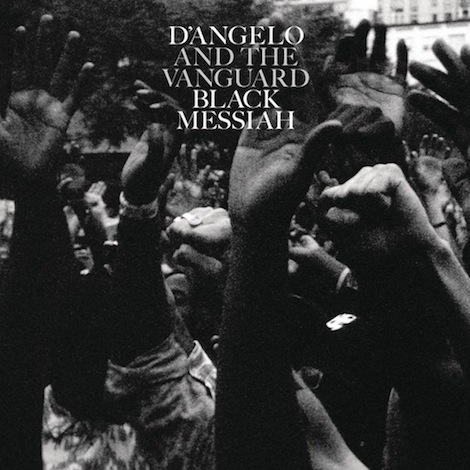

D’Angelo and the Vanguard : Black Messiah

It was a familiar scene: on a December night, I, like many other fans, sat waiting impatiently for a surprise new album to download. However, unlike Beyoncé’s album in 2013 – sprung upon on us with nary a hint – fans have been waiting for a third D’Angelo album for 14 years, secretly terrified that it would be the Chinese Democracy of R&B.

These fears were laid to rest as Black Messiah bubbled to the surface. A record of great depth and maturity, Black Messiah is the record of our time. Rushed to release in the wake the grand jury decisions on the murders of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, Black Messiah feels both timely and timeless. There is a sense of disorder and discomfort throughout the album — a feeling that underscores the daily anxieties of being Black in America.

In the tradition of albums that present honest truths about humanity, such as Sly and the Family Stone’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On and Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, Black Messiah feels urgent and, indeed, it sounds cathartic. It was the album that D’Angelo needed to make, and he’s speaking about things we need to hear. In the liner notes, D’Angelo says, “For me, the title is about all of us. It’s about the world. It’s about an idea we can all aspire to. We should all aspire to be a Black Messiah. […] ‘Black Messiah’ is not one man. It’s a feeling that, collectively, we are all that leader.”

This call permeates the album, urging listeners to open their eyes to the injustices in the world, from systemic racism (in “The Charade”: “all we wanted was a chance to talk / ‘Stead we’ve only got outlined in chalk”) to the environment (in “Till It’s Done (Tutu)”: “Carbon pollution is heating up the air / Do we really know? Do we even care?”). As cities continue to stage demonstrations, athletes raise their hands in protest on national television, and conversations about cultural appropriation by Top 40 artists take place, the time for this call. Again from the liner notes: “It’s about people rising up in Ferguson and in Egypt and in Occupy Wall Street and in every place where a community has had enough and decides to make change happen.”

Black Messiah may have succeeded on its politics alone, but the fact that the music itself is just so good brings it to a whole other level. D’Angelo’s knack for embracing and channeling his influences, while making them his own, is present with a vigor that is breathtaking. Black Messiah finds D’Angelo with renewed strength and flexing those musical muscles (who knew that he was just as deft with a guitar as he was with piano!). While many would have been satisfied with an album of 12 re-treads of “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” or “Lady,” it was clear that D’Angelo expected more from himself and thank God for that. His love for ‘70s funk is still present, with shades of Sly Stone and more prominently, The Stylistics. Trading the organ and keys in for guitars, the songs on Black Messiah swirl and groove with a kind of dirty funkiness that makes it stand apart from the sheen that often glazes pop music. There are moments in listening to Black Messiah that makes you feel like you’re in a small sweaty club, knowing that what you’re witnessing is incredibly special.

Black Messiah is a stunningly strong comeback, one that should allay any impatience in the long wait for its arrival. When I first listened to the album, a funny, left-field quote popped into my head: in Lord of the Rings, Gandalf remarks, “a wizard is never late, nor is he early, he arrives precisely when he means to.” It’s not often J.R.R. Tolkein and D’Angelo are uttered in the same breath, but it seems appropriate here. Black Messiah is the culmination of many years, yet not once feels tortured or overworked. It arrived just in time and it’s so good to have him back.

Similar Albums:

Prince – 1999

Prince – 1999

Sly and the Family Stone – There’s a Riot Going On

Sly and the Family Stone – There’s a Riot Going On

Erykah Badu – New Amerykah Part One (4th World War)

Erykah Badu – New Amerykah Part One (4th World War)