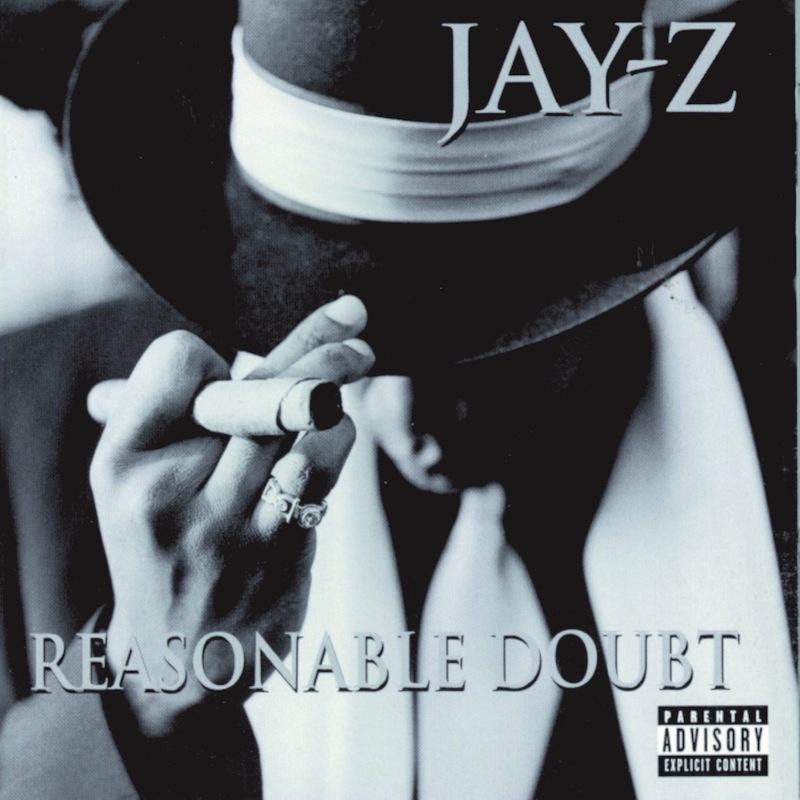

How Jay Z’s Reasonable Doubt launched a hip-hop legacy

“Who do you think you are? Baby one day, you’ll be a star…”

Jay Z began his rapping career in the late ’80s, but it took a long time before he’d garner the attention of any labels. Here was a kid from Brooklyn’s Marcy Gardens Projects who dealt drugs for a living and sold his rap tapes out of his car, anxious to build an empire and run the world. Jay Z’s career was off to a promising enough start, having been fortunate enough to tour with Big Daddy Kane at the early onset of his career. But despite the heavy exposure, he didn’t have the financial backing to give his career the necessary boost. He briefly landed with Payday Records, though the deal fell through due in part to the record label failing to market him effectively. So in an early business move, Jay decided to part ways with the label to carve his own path. With his small monetary returns and the help of his partner Dame Dash, Roc-A-Fella Records was born in a small office space on John Street near the Brooklyn Bridge.

Jay Z’s Brooklyn—the Brooklyn that serves as the backdrop to Reasonable Doubt—is not the Brooklyn we know now. The Marcy Gardens Projects still stands in the midst of Brooklyn’s gentrification; the transformation of a working class neighborhood to one with extravagant rents and mayonnaise shops. It seems hard to believe now, but Brooklyn wasn’t always a top destination. Reasonable Doubt presents the Old Brooklyn filled with grittiness, the crime and the absence of the American Dream. It’s the ways in which he expresses these vivid narratives that Reasonable Doubt, which just hit its 20th anniversary, remains Jay Z’s greatest achievement. While his later releases—such as the iconic Blueprint and the eclectic The Black Album—embraced pop in an effort to remain accessible, Reasonable Doubt is the record that solidified Jay Z’s career both as a rapper and entrepreneur. It even managed to sell modestly well for a debut record, though Jay Z would hardly ever rap like this again. In the ’90s, he utilized a mafioso persona to market successfully, but Shawn Carter’s origins were humble, coming from a life filled with poverty, corruption, and struggle. It’s easy to forget this now, given his massive net worth and business ventures like Tidal.

“Can’t Knock The Hustle,” 20 years later, remains one of the strongest album openers in rap. Despite his relative obscurity at the time, Jay Z managed to get Mary J. Blige to sing the infectious hook. The story goes: Dash had known Blige, asked her for a favor and paid her $10,000 in cash to be featured on the track. Though they went to great lengths to get her feature, it was worthwhile, since the hook is catchy and complements Jay’s ruthless verses. “Can’t Knock The Hustle” sets the tone. It is an outline of his story: Rapping was his side gig and selling drugs was his daily job. Folks in the neighborhood knew he rapped, but didn’t give it much thought. “Can’t Knock The Hustle” was specifically aimed at his closest friends, who doubted his rap career. Jay Z was expected to fail, though for him, that was never really an option. They all knew he rapped, but didn’t think it would take him anywhere. It’s a bold statement from a rapper who didn’t have a career, but in the end, his directness would pay off.

The narrative Jay Z weaves makes its unique character all the more compelling. Mafioso narratives were a predominant theme throughout, and fellow Brooklynite The Notorious B.I.G. offered an assist on that front. “Brooklyn’s Finest” is a masterful showcase of Jay Z’s skills. The feature between these two has since become historic and rightfully so since this was one of Biggie’s last appearances. On Biggie’s part, it was a risk to be featured on an unknown rapper’s album, and according to one of Roc-A-Fella’s lawyers, Biggie was a hard guest to get. But no time is wasted between either emcee. In some ways, “Brooklyn’s Finest” can be seen as a passing of the torch between Brooklyn rappers. During the studio sessions, Biggie and Jay sat behind the boards ready to record. When a producer dropped a pen and pad between them, they passed it back and forth, neither wrote their lyrics on paper.

According to Jay Z’s memoir, Decoded, “Coming Of Age” and “D’Evils” carry the same themes, but have their small differences. “Coming Of Age” concerns the story of a rising drug dealer under the training of a veteran hustler. Quite literally, however, it is also Jay Z presenting Memphis Bleek as his protégé. All throughout, it’s Jay naming all kinds of deeds that Bleek is willing to carry out in an effort to prove his worth on the streets. This ties to a much bigger theme: Proving his worth as a rapper to audiences. Matched with some extraordinary production that features a great Eddie Henderson sample, the exchange between Bleek and Jay Z reflects a cold-blooded tone of what life in Brooklyn used to be.

Conversely, “D’Evils” is much more political than “Coming Of Age”. While the former adds more to the narrative of Jay Z’s upbringing within the game to survive, “D’Evils” is the desire for money, power and respect and how it can all lead to violence, corruption and betrayal. While Jay Z has seldom been openly political, “D’Evils” is sort of an exception to the rule. The translation of “D’Evils” is a play on the word, pronounced as “Da Evils.” When Jay Z raps, “And the workings of the underworld, granted/Nine to five is how you survive, I ain’t trying to survive/I’m trying to live it to the limit and love it a lot,” paints a heavy portrait of young black men who have opted for a life of crime out of being deprived of other opportunities. But Jay-Z didn’t see the 9-to-5 life as all that attractive either. It was a search for something fruitful and prosperous. Meshed with a sample that borrows from Dr. Dre’s “Lil Ghetto Boy,” “D’Evils” is Jay Z at his finest here. For Jay Z, building an empire meant going big or going home.

In a 1997 interview, Jay Z says the album’s title was a reflection of how he felt he was on trial, because he knew he was going to be judged by his first major statement. The opportunities for a successful life at one point seemed distant, and Brooklyn—now an epicenter of culture and privilege—was a symbol of bleakness and despair. Jay Z has been part of that transformation as well. Reasonable Doubt serves as a goodbye to his old life, an honest portrayal grounded in great lyricism and storytelling. It is also one of his last records to pay homage to the greats of hip-hop before him, from the Biggie guest appearance to the wicked Nas sample on “Dead Presidents II” (which later started a beef). Jay Z’s debut still stands the test of time as a personal best. Although Jay Z’s recent albums haven’t packed the same punch, Reasonable Doubt cemented his legacy. He was a compelling presence from the start.