The ghostly, enigmatic music of Acetone

It seems we always remember the past as neatly-edited pages and stories in a dusty filing cabinet. The best moments are the most vivid and prominent, the center of memory. We all know this to be untrue—music, culture, “scenes,” much like life, is inherently messy and nonlinear. Even thinking of the musical past in terms of neatly anthologized retrospectives seems blasphemous to the uncertainty so many of these bands, eras, and movements faced.

So, in the fall of 2017, when the Seattle-based reissue/archival label Light in the Attic released an oddly curated compilation of a little-known Southern California band called Acetone, accompanied by an exhaustive book covering the band’s history by the writer Sam Sweet, I was skeptical, to say the least. Little was known of Acetone at the time—they had signed to Neil Young’s Sanctuary Records’ imprint label, Vapor, early on, released a slew of unique but not revelatory studio albums and EPs throughout the ‘90s, and frontman Richie Lee died by suicide in 2001. Their music was not on streaming services, their records virtually impossible to find in record shops (or Discogs for that matter—their self-titled album, Acetone, starts out at $302), and no merch, posters, or really any live recordings of any kind could be found. Their discography was scattered across Youtube by obsessive fans, which are minimal, and if you were lucky, you might be able to cop one of their CDs in a discount bin at your local record shop—I was the latter.

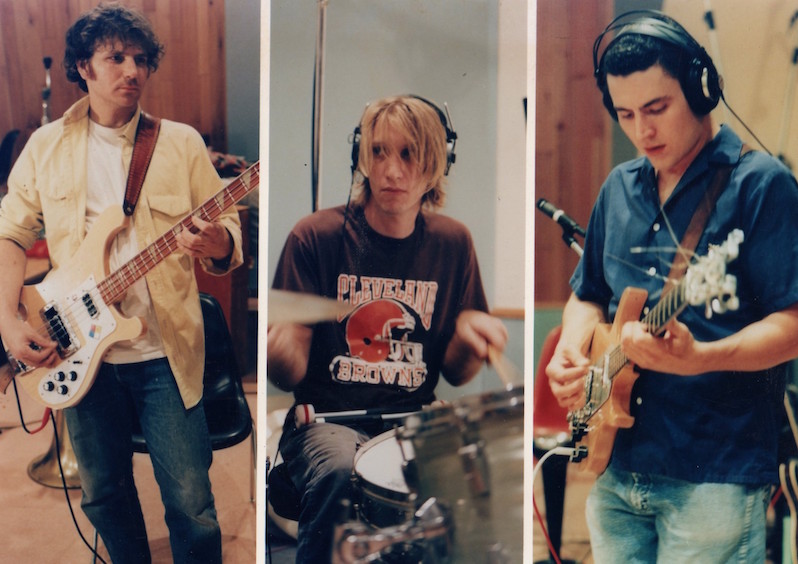

While companies such as Light in the Attic and the Numero Group have monopolized esoteric musical archival releases— with the media help of websites like Aquarium Drunkard—and can now actually bring a slim profit or critical recognition to these obscure and forgotten artists, the question still remains who, why, and how. A New York Times bestseller is not always a predictable feat; a pop-hit can stay for a week or become the song of the year; a trio of artists and ex-surfers from California who made woozy, dream-rock can come to represent how much was forgotten in the music industry when there was actually money involved.

This could be an issue of right place/right-time (or vice-versa). It could also be a symptom of cultural “natural” selection. We never really know what is going to stick, and oftentimes surprise ourselves with what does stick (even more so with what doesn’t). To me, regardless of influence—they really had none—Acetone is one of the most important indie-rock bands of the ‘90s. Where grunge, emo, slowcore, nu-metal, and scratchy indie-rock dominated the various scenes and movements of underground music in the ‘90s, Acetone channeled a slack jawed, minimalist psychedelic sound that melted—to listen to an Acetone song is to fall into a trance, gentle guitar leads and quivering bass lines alchemize into a gelatin-like hypnosis. That is, if you listen to LITA’s 1992-2001 compilation.

Acetone were also a rock band. They indulged in gnarling guitar solos, ear-blasting percussion, and traditional guitar-rock hooks. 1992-2001 paints Acetone as a no-frills dream-rock band that borrowed as much from the Velvet Underground’s soft side as Gram Parsons’ peak solo era—twangy lullabies and love songs, bits of noise scattered across a winding, pastoral landscape leading to a sunset on a scummy beach. And sure, every Acetone album or EP partially sticks to this mellow aesthetic, but a lot of the time they divert into absolute chaos, blissful noise and nasty guitar solos that might make Neil Young circa his “ditch trilogy” sweat bullets (courtesy of the brilliant, idiosyncratic guitar playing of Mark Lightcap). “Pinch,” the second song on Acetone’s 1993 debut album, Cindy, is an unforgettable rock song that documents the sickness of heroin withdrawal—singer/bassist Richie Lee howls “Sandpaper on my insides,” followed by “I tried to tell the doctor, but he just misunderstood / The way I’m feeling / And it ain’t no good.”

“The Final Say,” a deep cut from Acetone’s 1995 self-titled record is a mesmerizing love song that rolls and cuts through a swampy layer of brilliant interplay with Lee’s easily identifiable bass style and Steve Hadley’s loose, manic percussive aesthetic. There are always a handful of these types of songs on an Acetone record—heartsick, wild, and loud songs that act as a relief to whatever trance the majority of the music puts you in. It represents the dynamic styles and moods Acetone can effortlessly pull from. It seems that from each album or EP release, Acetone grew more bizarre, more unusual—to borrow from the oft-quoted line of John Peel referring to the Fall, Acetone were “always different, always the same.”

What remained was the ghost in every Acetone song. Through each lick, howl, or croon, you can hear the skeletons in Richie Lee’s closet taking a bite out of every second on record—his struggle with mental health and heroin addiction, his eventual suicide. Acetone never fit into a place for long, their talent never metabolized at the right time, their albums never finding the right label or crowd. They are outsiders to their core—but sometimes, these outsiders, the wallflowers and dropouts, the nerds and obsessives, create the biggest impact, the most beautiful art. And to abruptly come to an end via their frontman’s suicide feels, well, not surprising in hindsight. Not to say it is not tragic, a massive loss for independent music. This is all true. And in no way do I intend to glamorize suicide or addiction—these are serious, urgent diseases which should be treated with delicate care and immediacy. It’s just less than shocking that a tragic story of a band who “never was” ended in such a brutal, cold manner. Some stories just write themselves.

And this is not a far-fetched indie-fetishist claim of cryptic singularity—there has never been a band that sounded like Acetone, period. Even the martyrs of musical databases on the Internet (RateYourMusic, AllMusic) have difficulty categorizing or grouping together Acetone with anybody else. They were an enigma. And an understated one at that. The trio fueled their slow-motion, ghostly soft-rock by simplistic, albeit sagacious interplay—maximal minimalism. So how could we begin to categorize a band that dabbles in surf-rock, slowcore, dream-pop, country-rock, soul, punk, and flat-out rock and roll, and expect it to even make sense?

Masturbatory micro-genre listing aside, the point is that Acetone’s uniqueness was both their biggest strength and their biggest weakness. Of course it took a label like Light in the Attic to deliver a platform for Acetone to really come into their own reputation, to eventually shine like the chiseled piece of musical history that they are. This is a band who toured with and was always pushed by Mazzy Star, Spiritualized, and the Verve. If you are familiar with “alternative” music in any way or form, these are not small names. These are heavyweights. Beyond that? Acetone was signed to a label run by Neil Young’s team, who released records by Jonathan Richman, Tegan and Sara, Spoon, and Vic Chestnutt, among others. Acetone was always in good company, their sound always appreciated.

But when an artist dies tragically due to substance abuse or suicide, it can be difficult to divorce addiction from the art they created. Especially when said artist or band is getting their due via the posthumous, critical reconsideration method. How can we not hear death and suffering in Acetone’s music? Death is constantly gnawing at their otherwise “positive” sound. This image, however, distracts from all of the good and passion in their music. Three musicians were best friends for over a decade, picked and chose a selective, genius curation of influences, and recorded a handful of nearly perfect records. Anything beyond that is legend—we could search to decode and decipher the pain and meaning that might be in Lee’s lyrics or gentle timbre, or obsess over what they could have been. But at the end of the day, Acetone was a brilliant band caught between a particularly strange cultural erosion of industry and stylistic changing of the guard. They are the forgotten mavericks of a time displaced.

Do yourself a favor—buy the 1992-2001 compilation, or search for any of their full-lengths on Youtube (Cindy, Acetone, and York Blvd are excellent places to start) and try to catch a glimpse of Richie Lee’s ghost, watching over the room and manifesting joy and kindness into the world. We could use a little more of that.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.