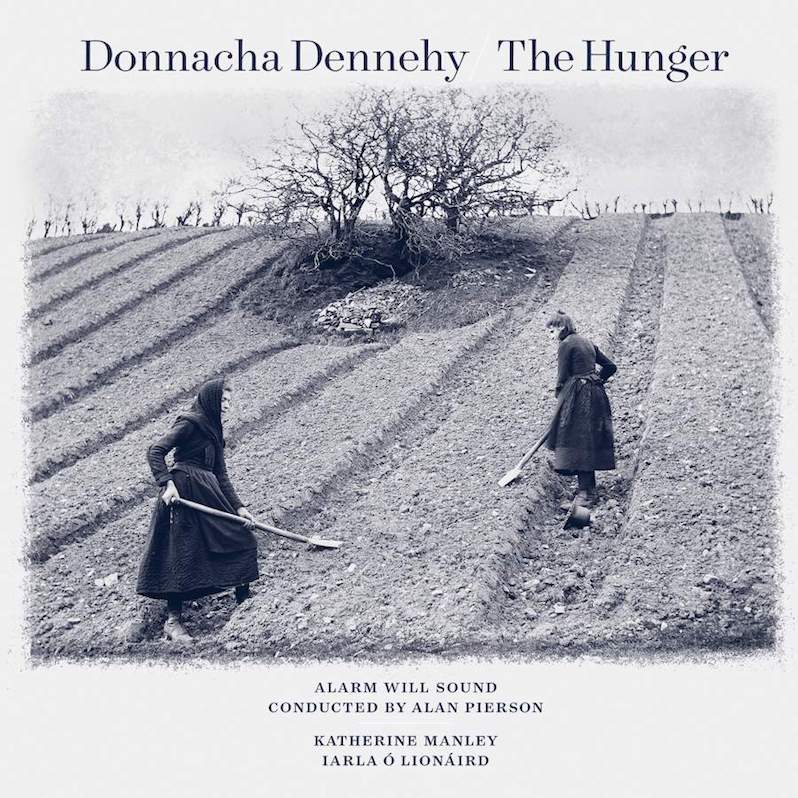

Alarm Will Sound/Donnacha Dennehy : The Hunger

While it was not their first album, most people discovered orchestral music ensemble Alarm Will Sound with their 2011 release Acoustica, a set of re-arranged Aphex Twin tracks played in chamber and large ensemble orchestral forms. On paper, this runs the risk of being, to be frank, corny as hell, coming across more like the tacky additions of strings to pop and rock songs than to proper chamber music drawing from contemporary records the way that older composers would draw from folk and popular music of their own time. But, like Christopher O’Reilly before them with his immaculate arrangements of Radiohead and later Nirvana and other groups in classical piano context, Alarm Will Sound earned both the respect of the academic music world with the robustness and strength of their arrangements and performances as well as the broader popular music world with their keen balance of fidelity to Richard D. James’ original compositions and the timbral changes and dives afforded to them in a chamber music context. Acoustica didn’t just feel like an orchestral ensemble riding the wave of a well-known musician; it felt like a considered and proper record that could live comfortably in either world.

Alarm Will Sound became, over time, a more modern equivalent to the Kronos Quartet, that famous string ensemble that over their 40-plus years together have played with people as varied as contemporary classical/opera composer John Adams and Paul McCartney, Philip Glass and Pat Metheny, The National and Björk. Alarm Will Sound have admittedly aimed at more peculiar spaces, choosing largely to record original compositions with composers rather than arrange their material after that breakthrough of sorts for them. The Hunger is one of these pieces, a modernist opera about the Irish potato famine for two voices, one a classical soprano portraying a real American journalist who went to Ireland in the mid-1800s to chronicle the state-imposed starvation and the second a sean-nós male voice, a type of Irish folk singing, depicting an unnamed sufferer of the famine. It’s best described as a modernist opera because, unlike a traditional opera, there is no dramatic movement, no shift of scenes or present-tense action. Instead the libretto is delivered through impassioned weaving dialogue, the voices at times overlapping, her shocked at the waste and suffering before her eyes and him merely suffering. It is a powerful portrayal of these kinds of quiet domestic horrors, of the kinds of brutalities states can mete out against the marginalized groups of their communities as the Irish were and are under British colonial rule, and underscores most powerfully the fruitless callousness of these tortures. The unnamed man suffers not for some grand purpose, not for some penance, is offered no beautiful salvation following the thinning and dying of his family and community; only quiet, only the pained croak of the starving, only death. The paradoxes and nihilisms of these extreme brutalities is harrowing and potent, especially penned by a composer and librettist who is so deeply entrenched in his own Irish heritage and artistic lineage as Donnacha Dennehy.

This is balanced by a score that sits most comfortably in the tense vibrating motionlessness of minimalist music. The oscillations nod to Steve Reich, dancing alight like cold white light streaming in pillars through stained and dusty windows, its harsh empyrean glare like a condemning gaze of god against blighted earth. The songs move harmonically less than they hover like the stillness of a scorpion’s tail. The influence that music like this had on the development of post-rock, especially the more orchestral groups like Sigur Rós, is palpable, that same sense of impossible tension in otherwise motionless constructs. The affect of the music is the same kind of intense lyrical sorrow that genres like doom metal, especially funeral doom and gothic doom, strive for but executed with a sense of perpetual tension rather than the sometimes overblown delivery that less sensitive groups of those heavier persuasions can sometimes deliver. There is an immense patience in this music, a willingness to tease and to have that organic and patient sense of breath and pace that makes music like this tend to swell and cast over in waves. It makes the transition to eerie beauty near the very end of the song cycle all that more heartbreaking, leaning away from the bad and cornball off-Broadway sense of cloying melodic and harmonic development for a more sophisticated and ultimately rewarding sweep. The inevitable corruption of that brief window of beauty feels emotionally the way that groups like Type O Negative or Pallbearer do at their very best, that tense twist of the knife right when you believe, impossibly, against our understanding of history, that perhaps there will be hope for these people.

It is hard to make compelling song cycles about these moments in history ironically because we know precisely how they go, how they move. The necessary narrative tension is dissolved by our understanding of where these historical stories must go. Instead, the composer, librettist and conductor must work to focus on the emotional narrative of those living souls within these moments, to make them lived tales rather than abstracted historical treatises. This is part of what makes Dennehy’s choice of such a profoundly intimate libretto, one with no dramatic action save for these impassioned witnessings and dialogues, so potent and along with them Alarm Will Sound’s sensitivity to gird the emotional harmonics and functions of that libretto. There is a careful balance at work between the trauma and nihilism we know from that horrible near-holocaustic famine and the tantalizing feelings of hope and despair of those that lived through them, one preserved well in this piece. The fact that Fleet Foxes was signed recently to the same label this was released on, a label largely known for orchestral “new music” of the Philip Glass and Steve Reich bent, makes sense here; Crack-Up feels like a folk parallel to these kinds of compositions, both The Hunger and Crack-Up offering viable windows into the world and heart of the other. Ultimately, The Hunger underscores why Alarm Will Sound are an enduring ensemble of growing acclaim and why Dennehy is a respected modern voice. It is a heartbreaking opera, one that needs no formal training to appreciate or follow. If you’ve heard a post-rock album, you will be able to parse these pieces and witness their slow pained beauty, icebergs cleaving and falling like tears into the blackness of the unbroken sea.

Similar Albums:

Fleet Foxes – Crack-Up

Fleet Foxes – Crack-Up

Black to Comm – Before After

Black to Comm – Before After

TENGGER – Spiritual 2

TENGGER – Spiritual 2

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.