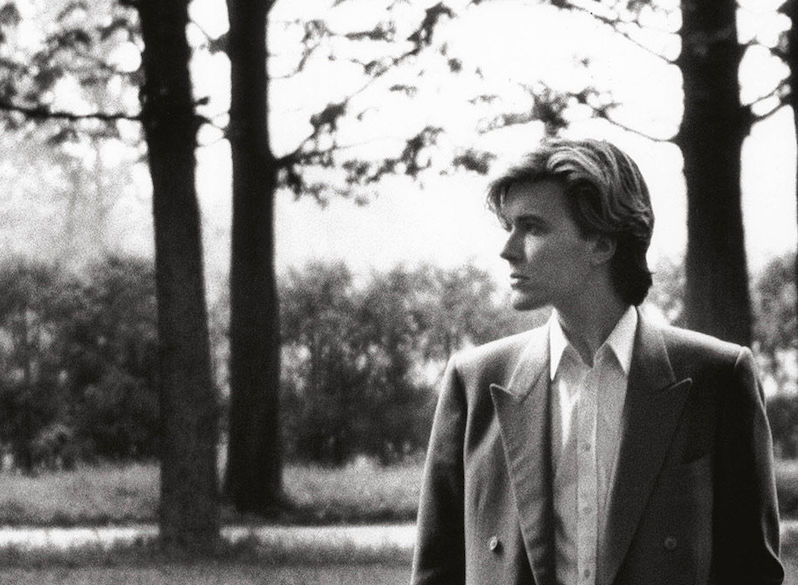

A Beginner’s Guide to the art-pop of David Sylvian

The past 40 years have done a tremendous job of clarifying new wave and ’80s music as a whole. For decades, we were fed lines about the clash of prog and punk, the supremacy of pop amidst its critical misunderstanding, the losing war of jazz against the encroachment of so-called inferior musical forms, and the anti-rock revolution first born in the bursting of hip-hop in its golden age after the primordial ’60s and ’70s of its youth, and all that without mentioning the development of synthesizer-led music from post-hippie prog fixation to pop powerhouse along with the loved/hated drum machine. It turns out, of course, that nearly all of these notions are wrong; or, more accurately, that they are like viewing a complex multi-faceted gem one face at a time, each alienated from the other so that their interrelations let alone the interior object they emerge from becomes obscured to the point of incomprehensibility.

There are few artists better suited to threading the needle of so many of these elements and, in doing, reveal that interior object than David Sylvian. Initially the frontman of glam band Japan, Sylvian had within a decade produced work ranging from punky and direct rock tunes, sophisticated pop and rock in the mode of Roxy Music’s later period, world music much like Peter Gabriel, progressive rock, ambient, post-punk, synth pop and much more. He was in many ways a fusion of the musical spirits of David Bowie and King Crimson’s Robert Fripp, taking the stalwart and deeply English musical adventurism of the former and fusing it with the technically-inclined and ravenously cerebral qualities of the latter. If Crimson’s emergence into new wave in its ’80s incarnation was meant in part to highlight the latent prog rock influence on that mode of music, then Japan and David Sylvian confirmed it. It wasn’t that either punk or prog had won the bloody musical war of the late ’70s but, much more curiously, both had, fusing at the hip to produce a much more wild and unfettered generation of musicians willing to do anything, from the technically demanding to the direct and powerful, in pursuit of musical adventure.

Sylvian’s career since has only featured a further fragmentation and explosion, encompassing jazz-rock, alternative rock, ambient, world music, electronica, New Age, prog and a number of collaborative works exploring the ever-fractalizing elements of this body of work. However, as important and noteworthy as his solo material is to understanding him as a musician, his roots and the work produced by Japan (and its reformed installment under the name Rain Tree Crow) cannot be overstated in regard to his overall body. As a result, in showcasing some of the best David Sylvian albums to start with, we have decided to slightly alter the normal format of our Beginner’s Guide, highlighting three works from his first band Japan (including one under a different name), then three from his solo body of work, so as to give as rich a possible understanding of him as a performer in a still compact and easy-to-digest format.

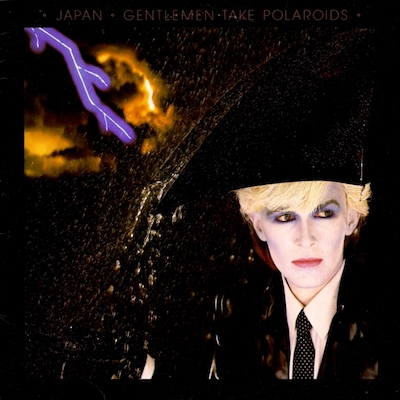

Japan – Gentlemen Take Polaroids (1980)

While the first three records by Japan show a deft navigation of the post-punk landscape, interpolating naive playing and glam rock structures against avant-garde and sophisticated synthesizer and guitar melodies, Gentlemen Take Polaroids was the first record that saw the band accelerate outward at a wild rate. Here Japan had morphed into what David Bowie might have become after the Berlin trilogy if his modus operandi weren’t so tenaciously set on regularly changing course; check the ambient pop of “Burning Bridges” against the atmospheric back half of “Heroes” for instance. The boys in Japan may not have known it at the time, but their sophisticated approach to the art rock and avant-garde influences on new wave and glam was to become the bedrock of progressive rock from the ’90s forward. The fact that Porcupine Tree would later pinch keyboard player Richard Barbieri as one of their own makes perfect sense when you hear this record, which embraces the longer run times that before had been saved for special occasions. Other groups of this era would likewise showcase shockingly prog chops, from Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s double record about a Samuel Taylor Colleridge poem featuring Yes’ Steve Howe on guitar during its 13-minute title track to the quietly robust jazz-rock performances girding Kajagoogoo’s work. But if groups like the Buggles and Oingo Boingo were focusing on bridging the nervy energy of New Wave with the classic form of progressive rock, Japan began to show the image of the future.

Listen: Spotify

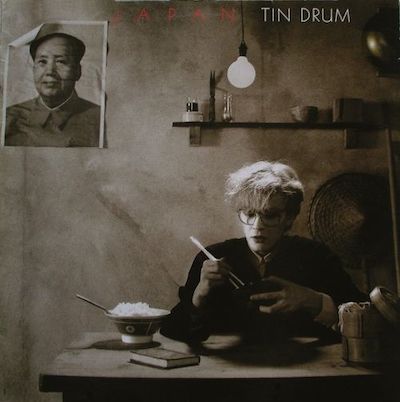

Japan – Tin Drum (1981)

If Gentlemen Take Polaroids was a vision of the future of progressive music, then Tin Drum was it in the flesh. Here, Mick Karn’s elastic and luxurious bass lines took on such tremendous form that his efflorescence into the master of the instrument he became was now self-evident; his future collaborations with Peter Murphy and Kate Bush seemed predestined. Likewise, Steve Jansen’s drumming here totally abandons the rock idiom for a substantially more exploratory sound, feeling more in touch with Manu Katche’s later drumming for Peter Gabriel or Phil Collins’ cymbal-less work for the same. However, the star of the show by this point was Sylvian himself. As stated by the band themselves, the making of Tin Drum strained relationships within the band, and Sylvian had even commented that Karn was basically a session musician on the project. While this would lead to the dissolution of the group, a real shame, it also led to this record, easily the crown jewel of the group (at least the material released under this name). Some critics at the time called it “mannered cubist pop” while Roland Orzabal of similar prog-pop group Tears for Fears would cite this album in specific as perhaps the greatest influence on the early years of his own esteemed group. The question of how to satisfactorily fuse prog, pop, and punk into an idiom that looked forward not backward, to the world and not just to Europe and America, finally seemed settled. So of course it all blew up after.

Listen: Spotify

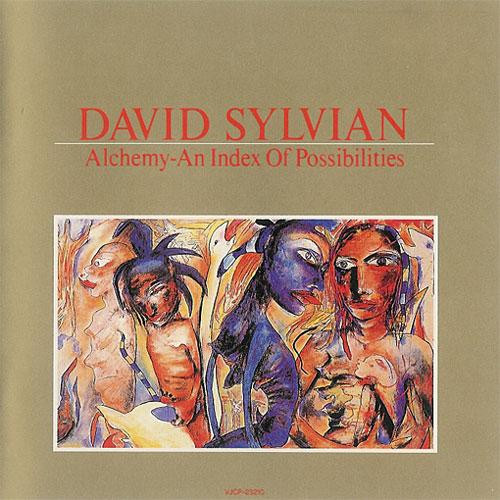

Alchemy: An Index of Possibilities (1985)

Much can be said of David Sylvian the art rock composer and player, all well-earned, but it is his work in experimental and ambient music that eventually earned him the reputation that catapulted him beyond that of his bandmates in Japan and Alchemy is the first moment that greater image came into focus. The original release of this record saw two lengthy pieces, roughly 15 minutes each, bookending a more standard sized piece; those two external bits resembled a prefigured hybrid of Peter Gabriel’s work on The Last Temptation of Christ soundtrack and its world music flair combined with the improvisational proto-post-rock of latter-day Talk Talk. The second of the lengthy pieces even included contributions from frequent collaborator Ryuichi Sakamoto, then primarily known as a member of synth pop/city pop legends Yellow Magic Orchestra but later to be a legend in his own right. The opening piece featured a jawdropping who’s who of musicians, including Holger Czukay the founder of German avant-rock/krautrock group Can as well as Jon Hassell, avant-garde contemporary classical and experimental trumpet player. This record is also notable for featuring a hybrid of the type of fusion of prog, ambient and pop guitar-driven work that King Crimson would later explore in the 90s, with Robert Fripp even appearing on the closing track. To refer to Alchemy as merely groundbreaking would never be enough; this is an entrance to the secret world where so much of the very best of experimental music was to be born. That the record was later reissued with additional material from the era only deepens our understanding of how much ground was being broken here. Still, we do not measure artists by broken ground but by evocation, color, and image, three things which this album has in spades.

Listen: Spotify

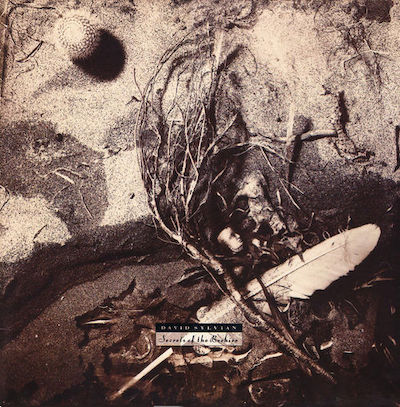

Secrets of the Beehive (1987)

For an album considered a failure by its creator, Secrets of the Beehive sure is great. It is well agreed that, of his solo material, Beehive is his masterwork, his Hounds of Love. Sylvian’s music always shimmered with a literary flair, leaning toward novelistic unfurlings of narrative within their spacious corridors, but where the Japan material was always streaked with a surreal magical realism and even the earliest Sylvian solo material saw stains of the mystic, here he brought himself to earth. One could almost imagine marble halls and white plaster walls, the curving doorways and the slabs of mahogany and oak that mark the entryways to the rooms of the great manse of this album. There are visions of billowing sheets and drapery, the scent of perfume, something gothic and romantic but soaked to the bone in daylight rather than abyssal dark. The sonic palette is perhaps closest to if latter day Talk Talk were to return to the songwriting idiom of The Colour of Spring, producing effulgent and sophisticated heartbroken progressive pop swaddled in luxurious strings and horns. Its most recent rerelease underscores a theme of Orpheus and Eurydice; this sentiment of ethereal longing feels especially insightful in understanding the firm character of this record. There is a clear character, a central “I”, but one set wandering in empty halls and bedrooms. There is always a sense of missing something, someone, departed, unreturning. There is the paradox of beauty, a dream home which retains its gorgeous character even as the figures that animated the dream are now gone and the strange emptiness this can make you feel. Everything prior was but mere short stories; this is the novel that was the labor of Sylvian’s creation.

Listen: Spotify

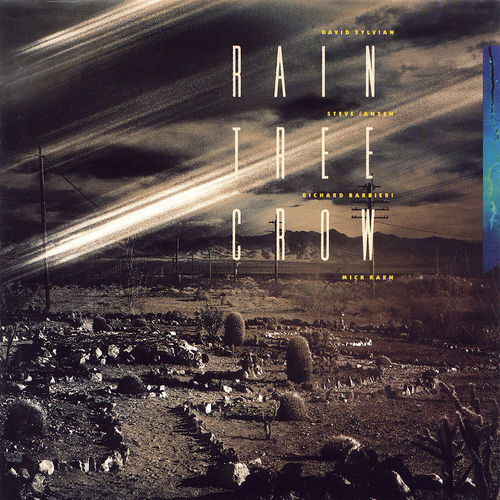

Rain Tree Crow – Rain Tree Crow (1991)

Japan would reconvene in the early ’90s under the name Rain Tree Crow, intending to properly return as a band in the long term and re-emerge into the pop sphere. What happened instead was much more (fittingly) curious; a one-off album, the last with all four core members of Japan playing together, expanding their Sylvian-driven compositional core with the increasing jazz and improvisational avant-rock chops of the other three musicians, who by this time had gone on to have many successful collaborations of their own. The result is a record that marries the abstract impressionistic ambient prog of Japan’s later years with a sophisticated and modern jazz-rock sense of arrangement and instrumentation. The line between this record and Porcupine Tree feels more or less direct. The trio of Jansen, Barbieri and Karn would go on to continue making records together while Sylvian would be left to only collaborate with one or two at a time at most. The historical reality brings a certain sweetness to this record, especially when juxtaposed both against where this band had started musically and where Sylvian had developed as a solo performer. The ease with which his expanded sensibilities post-Beehive slotted back in with the improvisational chops of his former bandmates is profound, not unlike the similar band reunions sprinkled across Bowie’s own career. For Japan as a group, this is perhaps the best album to start with, working backward to ever more wild and acrobatic post-punk glam rock or forward to increasingly abstract atmospheric rock. For Sylvian’s career, this is the most perfect fusion point of his identity as a band member and a solo artist, ironically only achieved on the most democratically composed record of the group’s life.

Listen: Spotify

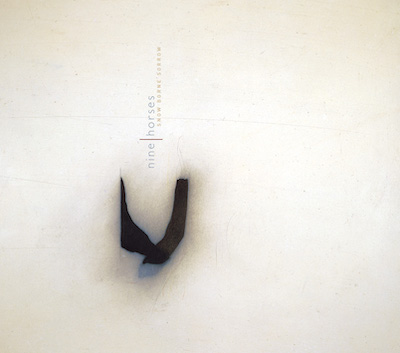

Nine Horses – Snow Borne Sorrow (2005)

The choice for the sixth and final record to include to highlight David Sylvian’s solo career was a difficult one. On one hand, there was perhaps the obvious Dead Bees on a Cake, but that record, while carrying charms certainly, has managed to age in a less satisfactory way than Sylvian’s work at it’s peak. Manafon, now just over a decade old, makes a strong case for itself as one of his strongest releases in his entire catalog. Likewise there was The First Day, the collaborative record between Sylvian and King Crimson’s Robert Fripp, offering an alternate view at Fripp’s first choice for what the ’90s would have looked like for Crimson with Sylvian with his John Wetton adjacent baritone at lead. But while that is an excellent record and likely would be the very next one on this list if it were expanded, it pales every so slightly compared to our chosen record. Snow Borne Sorrow is the debut record from Nine Horses, a group name chosen for the collaboration of Sylvian and his former bandmate Steven Jansen along with electronica producer Burnt Friedman. Sylvian’s trademark literary flair here is melded against an electronic avant-rock that feels like the middle space between Nine Inch Nails’ later and more sophisticated material with Sylvian’s solo work. The record leans in heavily to a jazzy and downtempo sentimentality, feeling like their stab at Sade’s similarly genre-blurring virtuosic pop. You might be disarmed at first by the lack of obvious fireworks here but, like the twin masterworks of Beehive and Rain Tree Crow, it is the deft and (there’s that word again) sophisticated figures and grooves here that will wind up etching themselves into your brain. Fittingly, much like Sylvian’s work credited solely to himself, the credits are a veritable who’s who of art rock, prog and jazz musicians. Ultimately, it is his undeniable signature that marks this record and makes it a clear fit for this list, much in the way that no one will mistake Tin Machine for anything other than a David Bowie band vehicle no matter the intention of the group itself.

Listen: Spotify

David Sylvian’s body of work is a bounty of treasures. Unlike certain performers, he was never afraid to collaborate and cross-pollinate, leading to a body of work that varies wildly in everything except quality. It is our hope that this list provides a digestible and approachable way to both parse his lengthy decades-long body of work as well as giving an adequate survey of the lay of the land, allowing mental fluency in his works spanning from pop to rock to prog to ambient to jazz and more. His hard-to-categorize career and position as being a musician’s musician makes truncating his career somewhat more nebulous than artists either much bigger or much smaller than him which tend to accrue a certain amount of canon works. For Sylvian, aside from Beehive, most of the remainder of his catalog swims in the same waters in terms of its position to long-time listeners and critics.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.

That you made a David Sylvian primer list is cool and admirable. That you left off Brilliant Trees is confounding. Your choice to include the Nine Horses album though, is spot on. For whatever reason, that record does not seem to have been appreciated as the utterly amazingly brilliant pop craft that it is. I think the lyrics make it and Beehive his best vocal works for sure. Even if the subject matter is rather sad. I would add one more consideration for the primer should be the Plight and Premonition collaboration with Holger Czukay. Perhaps his best instrumental/ambient work…haunting, insular, and the beginning of Sylvian’s transformation to an improv artist.