The album opens with a lonely, yearning trumpet note, answered by strings and a casual strum of the deeper notes of a cello. Slow piano notes, mid-range and soft, pair against the gentle buzz of trumpet, only to be answered by the harsh industrial clatter of a distorted guitar. All this is built over a tense drone, one that seems to shift its chordal center from a major to a diminished chord, passing from brightness to ugly discord and back, no real progression but for the diaphragm of consonance and dissonance. Two minutes pass before a blues riff with light compression on a guitar shows, harmonica and drums and piano not far behind.

The introduction to “The Rainbow” is a far call from the synth-pop of UK band Talk Talk’s first three albums. Granted this was not so much a sudden and inexplicable shift; only their debut, the underreported The Party’s Over, holds keenly to the style, with the well-regarded It’s My Life and The Colour of Spring each upping the art rock and lite prog inclinations bit by bit. This process is not terribly surprising; while the style of ’80s synth pop has since coalesced into its own pocket musical world with its own microgenres, it arose at the time as a hybrid form of the art rock/prog-leaning new wave intersecting once more with pop-rock in the caduceus of genre relations. Albums by Tears for Fears, Duran Duran, The Buggles and more interlaced their approachable synth-based pop rock with prog undertones and quiet influences. Talk Talk were, prior to Spirit of Eden, merely another of this caste, producing synth-pop/lite-prog art-rock hybrids.

But the power of Talk Talk’s Spirit of Eden is not diminished for lack of being some mystical, inexplicable deliverance of a record. The album, in one of many ways it is comparable to Miles Davis’ landmark Bitches Brew, has an easily understood history that undercuts some of the popular myths of its creation but whose aura is left undiminished when dispersing the mystery. And this is because of the very simplest reason any record remains potent throughout time, regardless of myth or social atmosphere: It is, without question, a masterpiece album and one of the very finest long-form art rock records made.

Talk Talk began with a traditional pop-rock lineup of vocals, keys, bass and drums. After their relatively underrated debut, though still their weakest, their follow-up It’s My Life saw them drop original keyboard player Simon Brenner for studio assistant Tim Friese-Greene. It was with Friese-Greene that Mark Hollis, the vocalist, guitarist and main songwriter for the group, would form a tight partnership, helping to spur them further out of their traditional space by encouraging pursuit of things like trumpet performances and more elaborate keyboard arrangements with more striking tones and timbres for the upcoming record.

The biggest contribution of Friese-Greene, on paper at least, was in helping co-write the title track, which became far and away their biggest hit and most enduring song outside of the art rock, art pop, post-rock and prog worlds, as well as co-writing two others on the album. But in practice, perhaps his biggest contribution was encouraging Phil Spalding, the bassist of Mike Oldfield’s band who was making an uncredited stand-in on a track for technical reasons, to record dozens of takes of the single song he was performing on, which were then meticulously combed over and assembled into a highly-edited final cut for the record. This method would later go on to define the totality of the sessions of Spirit of Eden and to the sole record that would follow it, something that is sometimes wrongly attributed as new to those records. It actually finds its roots on their biggest selling record.

In many ways, The Colour of Spring is a dry-run of the two masterpieces that would follow. The brief experiments with replacing synth sounds with organic and acoustic sounds on It’s My Life was deemed a success and, off the back of the commercial performance of that record, they were granted an advance large enough to procure players such as the long-time guitarist for Peter Gabriel, the harmonica player of art-rock weirdo savant Rory Gallagher’s band, and (inexplicably) Steve Winwood. The resultant album was a trial of the more open arrangements that would come to dominate the form of Spirit of Eden, with the average run-time ballooning from four minutes to six and a closing track coming in at just over eight. The songs were still written in largely the traditional manner, Friese-Greene having graduated to full composer alongside frontman Hollis as they worked out skeletons for the tracks that collaborating guest musicians would fill out with improvisations which were then highly edited to fit the cloudy classical/jazz-inspired timbre of the record. It is easy to imagine a world where this tentative experiment did not fare well, and instead of moving on to produce the two masterpiece foundational records for post-rock and contemporary prog and art rock, Talk Talk had instead been relegated to return to traditional synth-pop. However, despite faring slightly worse in the U.S., The Colour of Spring became their highest selling record up to that point.

What follows after The Colour of Spring is a widely-related tale; the band entered the studio, 13 collaborators and a choir in tow, and set about emulating the studio methodology of Miles Davis’ electric fusion years, producing dozens of hours of group and solo improvisation around keys and themes that were later painstakingly edited into form. The work was so fruitful that the first three tracks were originally sequenced a single tri-part 20-plus-minute epic, the foundational song for post-rock that would go on to be a key inspiration for Bark Psychosis in the creation of their record Hex that would be the first album to be named post-rock by critics. The band had graduated from synth-pop to art-pop to the broader experimental world of art rock.

As intriguing the methodology is, we are not moved by mere methodology. Nor are we compelled by mere history. What mattered then as matters now are the songs and how they sit together, what they evoke in us and what colors they play with.

***

My first encounters with Talk Talk were insubstantial: hit singles played on pop radio while sitting in the back seats of cars driven by baby sitters and cousins, the No Doubt cover coming out when I was in the eighth grade forcing my snobby music nerd ass to go revisit the original for the sake of cred, and other moments like that. Nothing was substantial about my interaction with the group until the summer of 2010. I lived at home then, returned from college without yet having received a degree, nursing my worsening mental health. I had made a suicide attempt in the middle of the summer, one that thankfully failed, and spent all of a single day in an outpatient group therapy for suicidality before calling it quits. (In fairness, hour 7 of the 8-hour treatment was coloring, with a strict “no talking” policy enforced. I drew an octopus with a wizard hat.)

Group therapy having been a bust, I began a regimen of antidepressants and struggled to return to school. It was painfully apparent to everyone, myself included, that between the debilitating paralytic panic attacks and tendency to sleep on the bare box spring of an undressed mattress that I was getting worse, not better. It was in this state that I dug out my copy of Spirit of Eden and its sister album Laughing Stock that I had acquired in high school as a movie theater usher blowing all my spare money on books and records.

I remember being curled on the wooden slats of the box spring, the firmness pressing into my back in a way that hurt, a hurting that made me unable to deny the presence of my body, as the album drifted over me from laptop speakers as my computer played the record from iTunes. The computer was half-opened like a steamed clam, resting in the space between my knees, my chest and my chin. The album cut into me like a knife. Hollis’ voice felt weak like mine, an abstract sense of the thought. The crescendos of the record and the bluesy dissolution of those tender alternative rock builds felt like Sigur Ros shot through with pain.

The chorus of “Eden,” the second movement of the tri-part opening suite, goes: “Everybody needs someone to live by.” This part comes after a particularly bluesy progression, the chorus’ vocals sung in a pained register by Hollis underneath organs that creak and groan like a gospel of passion in the traditional sense, the bodily and spiritual suffering of Christ before the agonies of the cross. “The flower crushed conceives / a child of fragrance so much clearer / in legacy.”

There is a namelessness to art, an ecstasy that is the precise transfiguration of sentiment into art in the artist that is then mirrored by the receiving audience; it is not in exegesis that we receive art spiritually but in ecstasy, and through ecstasy the interior sentiments of art are revealed in ways that are not always explicable in purely textual ways from the outside encasing shell. Which is to say in a certain way that the way those words felt to me in that miserable state cut deeper than I can easily describe, putting a voice to my pain as much in near-nonsense poetry as it did in the tenor and timbre of the instruments.

***

Every moment of the record bleeds tenderness. The tenderness comes precisely from the fallibility of the acoustic instruments, the waver and quiver of reeds and horns and the imperfect strum of a guitar against the backdrop of piano so earnest you can practically imagine the player leaned, eyes closed, head bowed over the board. It is also precisely why so many takes were needed; this otherwise bare methodological fact is brought to life by the sound of the record, where Hollis and Friese-Greene sought not the takes that were the most perfect but had the most ambiance, contributed to the wounded and yearning tenor of the record most perfectly.

It is, in a certain light, the same method that Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois brought to U2 when they transformed them from a political post-punk band to an experimental/artful pop rock group. The same atmosphere is maintained, that of subtleties of notes mattering as much if not more than the precise notes themselves, texture and resonance carrying the songs more than pure earworms. But the focus is still on relatively simple melodies and rhythms; the tricks of the record are buried relatively deep, obscuring an oboe here or a clarinet there in the mass of sounds of denser moments, the instrument meant to be felt but not heard.

In the dead center of the track “Inheritance,” a horns-and-woodwinds quartet opens up, all other instruments save drums silent, as they play a Debussy-inspired classical passage that focuses on the tension of sustained notes subtly shifting. Moments later, the distorted guitar appears, presaging the vocals which themselves silence the stringed instrument, replacing it with plucked double-bass. A warbling pump organ comes in, and with it the horns and reeds return, weaving a bird’s nest of sound.

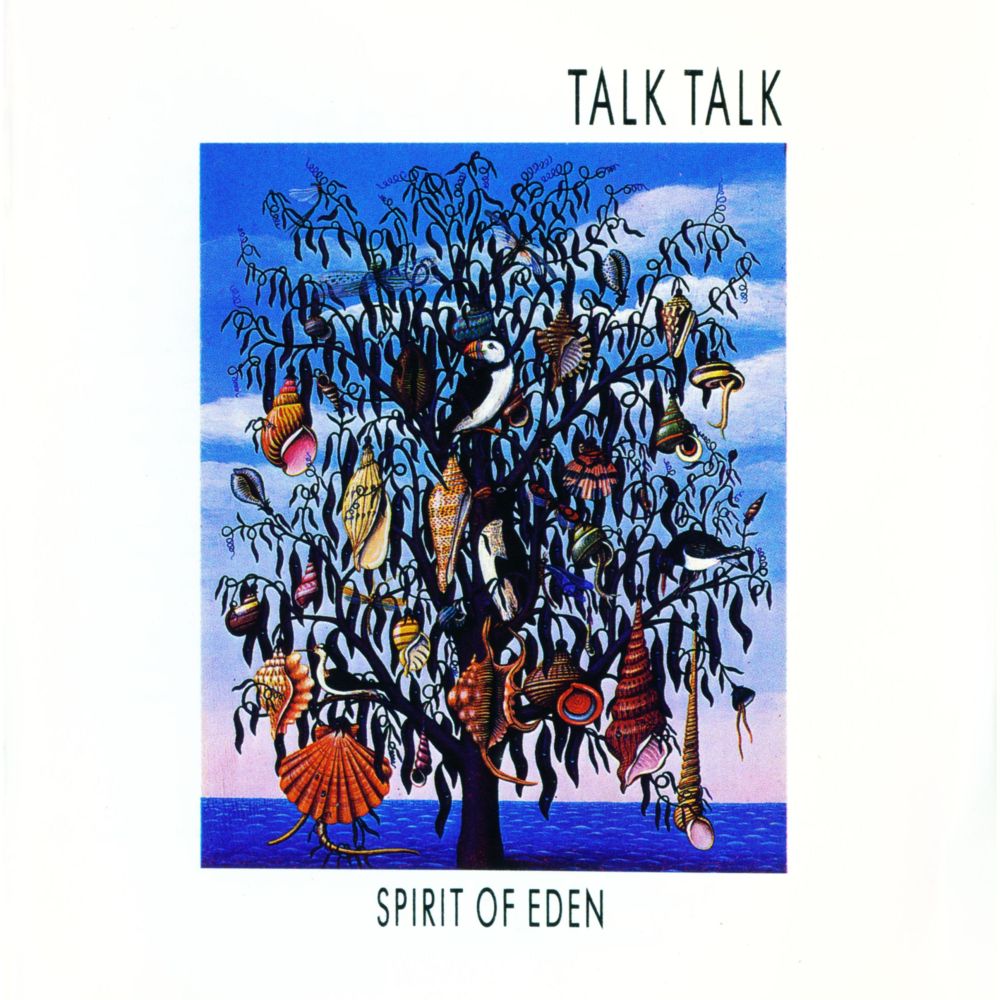

The mental image of the record is a keen one; dead limbs of a living tree, barren save for rotting leaves and absent nests. The branches are the instrumental lines, untreated and rough, too well-recorded to be lo-fi but too humanly played to be over-produced, never quite knitting together tight but instead embroidering the loose image of tender and broken song. The image of the half-dead tree that yet survives was so keen they dressed not only this album’s cover with it but also the next; it is an image, too, which scores the emotional passage of the album and why it burrowed so deep in my heart in that miserable place.

***

The legacy of Spirit of Eden is impossible to overstate. Not only did the record confirm the instincts of the band as fundamentally sound, leading them to produce their equally masterful final studio record Laughing Stock, and not only did they more or less single-handedly give birth to post-rock through it, but they also shaped the form of contemporary progressive rock. Where prog of the ’60s and ’70s had been founded on fixing jazz and classical thoughts to the pop and rock forms of their time, so too was a new form of progressive rock being developed in the late ‘80s and early ’90s. Groups like Porcupine Tree were forming, and groups like Marillion were reconfiguring themselves, internalizing the lessons of ’80s college rock and early alternative rock. Talk Talk, with Spirit of Eden and its follow-up Laughing Stock, were widely cited as a way forward. Many of the songs are chorusless, or structurally ambivalent to what could be considered their choruses, in a manner that felt befitting of progressive rock. Around the same time, groups were forming that were playing in a deliberately retro style and getting press doing so, but there was a thirst for something that held the same spirit but dealt with newer sonic ideas; it is hard to imagine we would have a group like Gazpacho without the legacy of Talk Talk.

Spirit of Eden ranks as one of the few instances where the belabored and expensive dream project was truly worth it. Part of this, if I had to guess, comes from how it tunneled inward rather than outward. Where so many other projects with a similar grandiose history of spiraling budgets and aimless sessions peters out into nothing, Spirit of Eden was always guided by an invisible interior thread to be more evocative, no matter what that evocation precisely was. This is why, in a wordless way that defies whatever Hollis’ pained English blues howl (such a far cry from his pop croon which so clearly inspired Thom Yorke), Talk Talk are able to conjure an emotional pain that is often deeper than most doom metal. The closest comparison that could be made to that world would be Bell Witch, another group that plays with sense of space and sparseness and is unafraid to let vocals be borderline febrile. It is the witnessing of weakness in that which strives that can sometimes be substantially more painful, in its own melodramatic way. Where previous Talk Talk records were moody dance halls, Spirit of Eden is a lengthy sigh in a hospital bed where, beyond the window, wait trees without leaves in autumn air, not yet dead.

Note: This article was originally published in 2018 and has been updated.

When you buy something through our affiliate links, Treble receives a commission. All albums we cover are chosen by our editors and contributors.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.

That completely captures the spirit of this record for me, too. Well put. This record was released when I was in university and at a particularly low and vulnerable point in my development. It is difficult to put into words how profoundly these tracks affected me. This album recognizes how frail and, at times, dismal the human condition can be, but also lights a path, albeit dimly, forward. Listening again, nearly thirty years later, brings me back to that time in my life and is a sonic hug of reassurance that things have a way of working themselves out. We live, we love and we grow. Everybody needs somone to live by, indeed.

Jimmy,

Seems a lot of people are jumping on the band wagon, saying how great it is, maybe the same people who are professing it to be a master piece now. It was and always will remain a masterpiece, a truly living work of art, that touches your soul, it takes you to a safe place from all what’s going on in the world, time gets lost when i listen to this .

It is the most underrated piece of work ever written. Talk Talk remain a truly unique and ground breaking band.

I appreciate this touchingly personal review of an album I also view as a masterpiece. I discovered it over 20 years ago, 10 years after its release , and cherish it to this day. Much like you describe, I believe, it still has the capacity to bring me to tears. Thank you for sharing with us. I hope and believe Mark would appreciate it.

I still prefer Laughing Stock but this is a great album.