A Beginner’s Guide to the shape-shifting samba of Jorge Ben

Before he found music, Jorge Ben wanted to play football. His parents had other aspirations for him—doctor or lawyer, naturally— but when he picked up a guitar as a teenager, he quickly developed a knack for songwriting. And before he turned 20, he wrote what would become one of the most recognizable anthems in Brazilian pop music, “Mas, que nada.”

Jorge Ben—later changed to Jorge Ben Jor, apparently when George Ben received one of his royalty checks—has left a massive and lasting legacy on popular music in Brazil and worldwide, having penned a number of some of the most enduring songs in samba and MPB, as well as having redefined himself throughout his six-decade career, expanding his sound to incorporate soul, rock, funk, jazz and orchestral pop. And though his 29-album catalog isn’t quite as expansive as that of peers Caetano Veloso (37) or Gilberto Gil (41), it’s rife with innovation and unconventionality, with an influence that stretches from the Tropicália movement to contemporary Brazilian artists such as Sessa and Seu Jorge, as well as—somewhat controversially—Rod Stewart.

In March, Ben turned 80, and in January, his debut album hits its 60th anniversary, which makes this midpoint an appropriate moment to dive back into his catalog and offer a selection of the best Jorge Ben albums for those looking to dive into his vast and influential body of work.

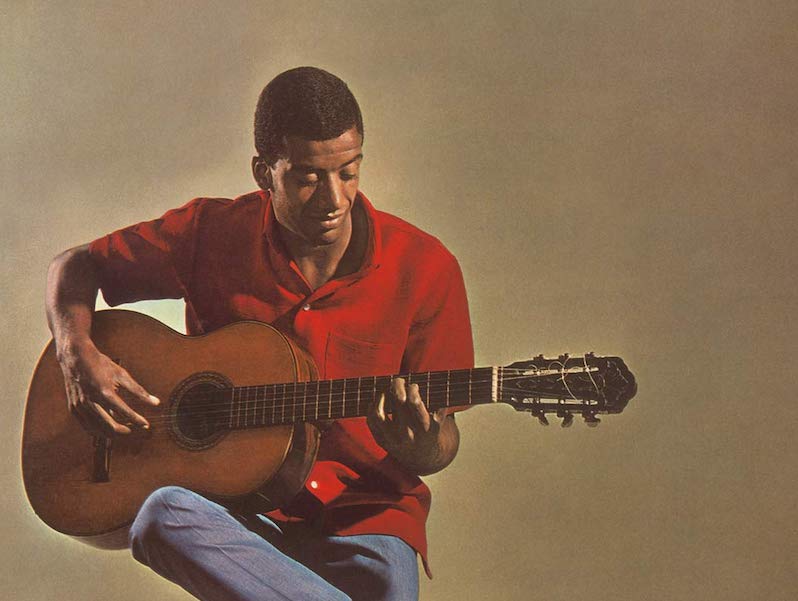

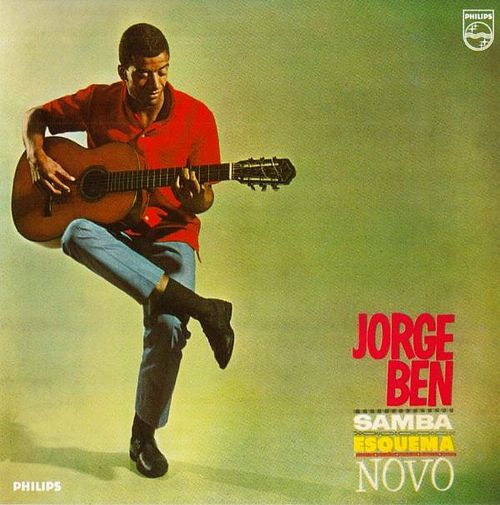

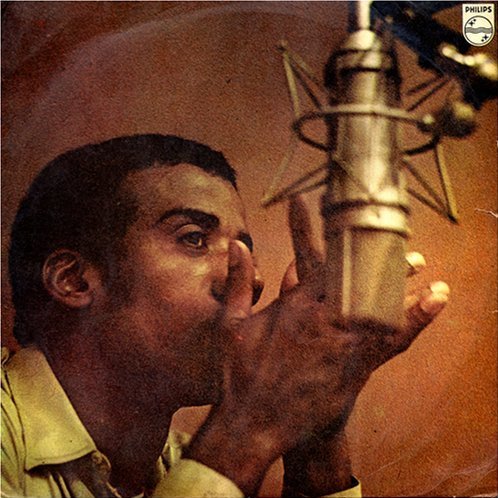

Samba Esquema Novo

We start this beginner’s guide, well, from the beginning. Samba Esquema Novo is easily among the best Jorge Ben albums, recorded and released when he was just 20 years old—pulling off one of the best samba albums of all time as he closed out his second decade. An astonishing accomplishment, that, and to make the feat all the more impressive, it opens with “Mas, que Nada!”, a Ben original (with roots in another vintage samba song, José Prates’ “Nanã Imborô”) whose influence on popular music—Brazilian or otherwise—is immeasurable, becoming a bigger hit for Sergio Mendes later on in the ’60s and then being revived four decades later by Black Eyed Peas. It’d be easy enough to stop there—once you’ve cemented a standard in the canon, everything else is gravy. But the 28 minutes of Samba Esquema Novo is spectacular beyond its most famous song, the young singer/songwriter’s soulful rasp lending each of the song’s bright, horn-driven arrangements an emotional gravity beyond their breezy sensibility, from the urgent rise of “Rosa, Menina Rosa” to the commanding fanfare of “Vem, Morena, Vem.” The album’s title translates to “new style samba,” and though it’ll be 60 years old in January, it sounds as fresh as the day it first hit shelves.

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Turntable Lab (vinyl)

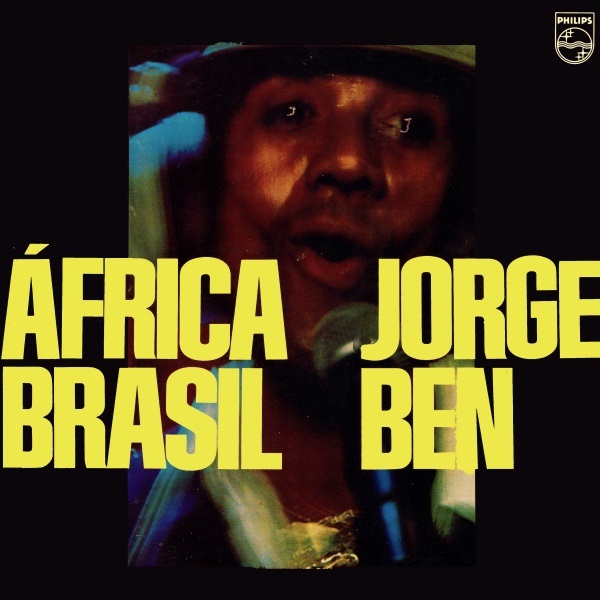

Africa Brasil

From his classic samba debut to his deeply funky late ’70s masterpiece. There are 12 albums between Samba Esquema Novo and Africa Brasil, but those two albums are crucial bookends to a two-decade run of studio recordings that are mostly consistently strong, often incredible, and frequently harboring sonically and thematically surprising material (like the one about alchemy—a solid contender, along with this one, for the best Jorge Ben album overall). África Brasil is Ben at his most electric, incorporating more pronounced elements of North American funk—as well as the message of Black Power behind influential albums by the likes of Sly and the Family Stone—in addition to the Afro-Brazilian rhythmic pulse that drives these 11 anthems. It’s also an album that moves to a similarly hypnotic rhythm as that of Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat, albeit with grooves that resolve themselves in only a fraction of the time as a fiery track like “Zombie.” A pair of them—”Ponta da Lança Africano (Umbabarauma)” and “Taj Mahal”—are among his best known songs. The former, perhaps the best song ever written about football (soccer, not NFL), is an undeniable banger of funk intensity, whereas the latter earned much of its fame through somewhat more notorious means, its hook having been lifted by Rod Stewart in “D’Ya Think I’m Sexy?” But who could blame him—if genius steals, then best to steal from a genius. Deeper into the album Ben revisits his alchemical concepts for a Betty Davis-like vamp (“Hermes Trismegisto Escriveu”), honors a mythological woman on the sultry “Xica da Silva” and goes psychedelic on the intense closer “Zumbi (África Brasil)”. A funk and samba-rock masterpiece through and through, but the road that leads here is every bit as fascinating.

Listen: Spotify

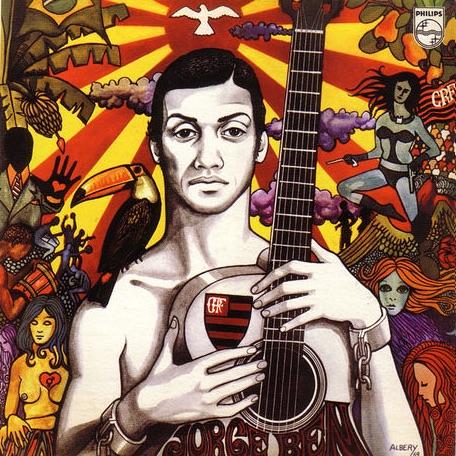

Jorge Ben

In the late 1960s, the Tropicália movement took hold in Brazil, with artist such as Caetano Veloso, Os Mutantes and Gilberto Gil each taking Brazil’s signature samba sound and merging it with psychedelia, socio-political critique, absurdist humor and modern sonic treatments. Ben didn’t appear on the original Tropicalia Ou Panis Et Circenses compilation that serves as its defining document, and wasn’t specifically part of the movement, but his influence and connection to Tropicália is significant. For one, he wrote “A Minha Menina,” one of the highlights on Os Mutantes’ 1968 self-titled debut album. And in the 1970s, he recorded an album length collaboration with Gil. Likewise, he delivered a masterful Tropicália album of his own on 1969’s Jorge Ben. A comeback of sorts for the singer/songwriter, who’d parted ways with Philips Records three years prior due to a string of underperforming albums. He returned to the label with this album, however, which in turn offered a more vibrant and inspired set of songs that reveled in the psychedelia of the era and featuring some spectacular string arrangements from José Briamonte and Rogério Duprat. And though it frequently sounds like Tropicália (particularly on the aptly titled “Pais Tropicál”), the songs are more often celebrations of everyday people—a street vendor turned Carnaval Queen on brassy opener “Crioula,” or the first appearance of a recurring character named Charles on “Take It Easy, My Brother Charles,” a celebrated fictional character in a favela underworld. It’s an album at turns bold and immediate, easy to love yet rife with strange detours, like the space-age psych-folk of “Descobri Que Sou Om Anjo.” Less a reinvention than the result of a newfound inspiration, it found Ben entering a new era that saw him release some of the best music of his career.

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Merchbar (vinyl)

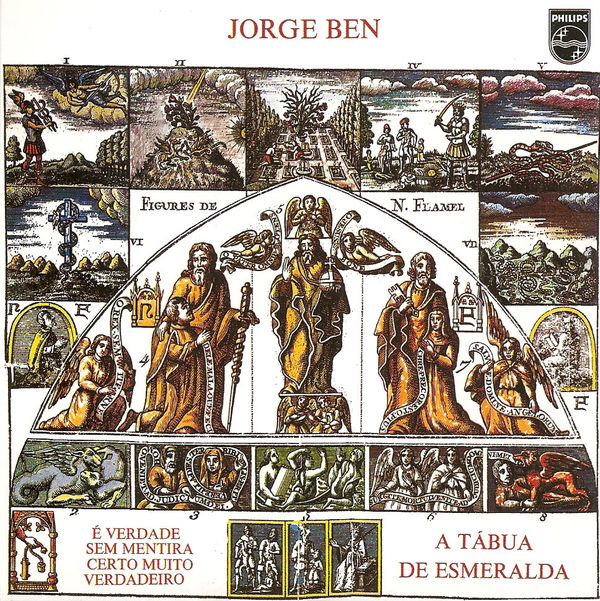

A Tábua da Esmeralda

In 1974, more than a decade after his debut album and only five years removed from his foray into the more psychedelic realms of Tropicália, Jorge Ben embarked on a project that few likely saw coming and, even today, sounds like a pretty unlikely artistic direction (that is, until you consider fellow Brazilian artist Tim Maia’s twin funk albums inspired by his newfound, if short-lived religion). A Tábua da Esmeralda, or “The Emerald Tablet,” is a concept album of sorts about theosophy and alchemy. The title itself refers to a tablet of mythic lore, and its songs concern figures such as German Renaissance philosopher Paracelsus, Hellenistic icon Hermes Trismegistus (who also appears on África Brasil) as well as Nicholas Flamel, whose 14th century illustrations grace the cover art—the only one here that doesn’t depict Ben, himself. And somehow, in spite of how intellectual and even abstract some of the material might be at its core, it represents some of the most absolutely stunning music Ben ever recorded. It’s often emotionally wrenching, Ben’s voice reaching heights of pathos he hadn’t before on tracks like the incredible “Errare Humanum Est,” which isn’t so much a showcase of skill but raw feeling (though the song’s orchestral arrangement is utterly gorgeous). Likewise, Ben employs his voice almost more like an instrument at times, his improvisations on “Menina Mulher da Pele Prata” punctuating a climactic highlight. And on standout “O Homem do Gravata Florida,” he even approaches the immediacy of the best moments on África Brasil. This isn’t Jorge Ben’s most immediate album, but it’s arguably his most ambitious—a masterpiece of eccentric vision and breathtaking composition.

Listen: Spotify

Força Bruta

Jorge Ben entered the 1970s with even more sophistication in his songwriting than his output in the ’60s, but with just as much imagination. Força Bruta is less bound by a bold, underlined unifying aesthetic or theme in the same way that albums such as A Tabua da Esmeralda or África Brasil are, but it’s no less immediately striking. “Oba, lá vem ela,” just like those of the four other albums selected here, is an immediately arresting leadoff track, opening the door to a kind of new era for Ben, one defined as much by the creativity of his compositions as the gravity behind his songwriting, less occupied by words chosen for their sounds alone and instead featuring stronger narratives and more acutely drawn figures, particularly women—his wife and muse Maria being a primary influence—as well as the meditation on race and Ben’s identity as a Black artist in the context of marginalization of Black Brazilians on the sublime “Charles Jr.” Yet for all the seriousness of the songwriting itself, there’s a looseness in the music that counterbalances it, Ben’s backing band Trio Mocotó having done minimal rehearsal before recording, and as such the music breathes as much as it grooves. It’s not a stretch to compare this to an album like Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, as well as a Brazilian contemporary like Novos Baianos. The title, which translates to “brute force,” carries a bit of irony to it—despite the heavier socio-political themes, the music flows with an ease that marks it as one of Ben’s most effortlessly enjoyable sets of songs.

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Turntable Lab (vinyl)

Next Steps: It’s hard to go wrong with any of Ben’s albums from the 1970s, though 1972’s Ben stands out in particular for its mixture of outsized arrangements and moodier pieces, falling somewhere between Caetano Veloso’s most vibrant material and the melancholy grandeur of Chico Buarque. Three years later, Ben collaborated with fellow Brazilian music legend Gilberto Gil on Ogum Xangô, and it’s as spectacular a meeting of two greats as you can imagine, defined primarily by looser and longer compositions, including an epic, 14-minute version of “Taj Mahal.”

Advanced Listening: A less heralded but by no means less worthy listen is 1971’s Negro Lindo, Ben’s follow-up to Força Bruta. It juxtaposes lushly arranged orchestral pop against folk-samba with prominent harmonica, and even some fairly intense moments like “Cassius Marcelo Clay.” And driving the point home that Ben could do no wrong in the 1970s, his 1975 album Solta o povão bridges the deep groove of África Brasil with the mysticism of A Tábua da Esmeralda, comprising the best of two wildly different yet interconnected worlds.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.