Being a rock star is nobody’s backup plan. There’s no security, no guaranteed salary or benefits, and even real success is an increasingly intangible thing—going on tour and being signed to a record label doesn’t necessarily mean being able to quit your day job. And having an audience doesn’t mean your bills are paid. Perhaps in some version of the universe there’s an aspiring claims adjuster who just can’t hack it and hangs up his clipboard to headline stadiums, but not in this one.

For Jorge Ben, however, playing music wasn’t at the top of the list. The Brazilian singer/songwriter didn’t originally set his sights on music, and his parents certainly wouldn’t have suggested any such ideas. His father wanted him to become an attorney and his mother preferred that he become a doctor, he told the Chicago Tribune in 2005. But he had other, if similarly impractical ambitions: “I wanted to be a soccer player.”

Jorge Ben—born Jorge Duílio Lima Menezes, and later changed to Jorge Ben Jor in 1989—didn’t rise to fame through his home country’s biggest sport, though he did pen a number of songs about futebol. (Brazilian musicians have, by and large, been fairly prolific in this arena, and many of those songs are phenomenal—no shade to the similarly prolific UK pranksters Half Man Half Biscuit.) Ben’s 1972 song “Fio Maravilha,” which translates to Marvelous Son, is a tribute to a fabled moment in the career of Brazilian footballer Joao Batista de Salas, who despite being immortalized and honored in song, actually sued Ben for using his name without permission, though accounts of how and why the lawsuit came about vary depending on who’s telling the story.

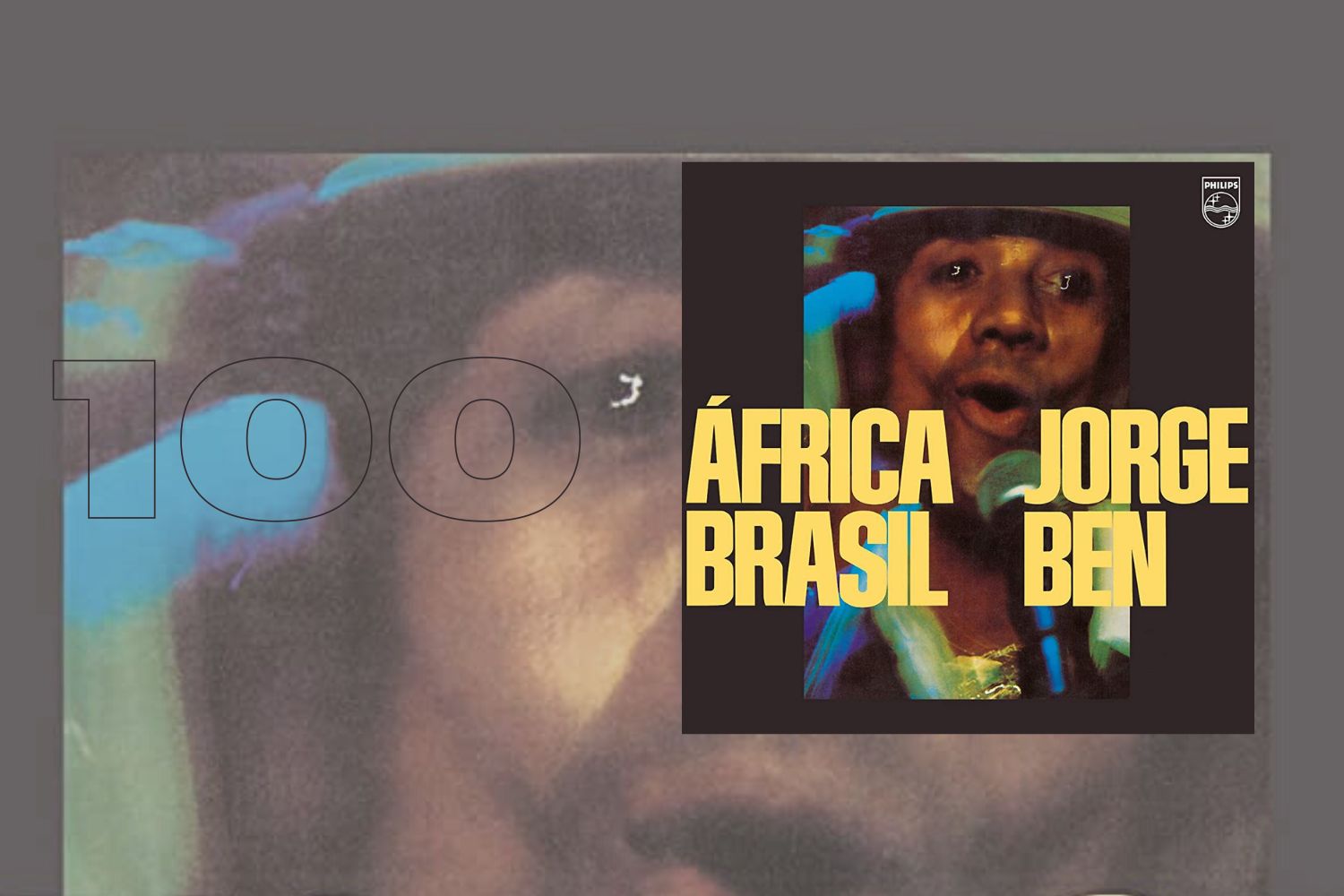

Yet Ben’s greatest football anthem is, without question, “Ponta de Lança Africano (Umbabarauma)”, the hard-driving, phase-shifting, superhumanly funky leadoff track on his 1976 album África Brasil. Written about an African striker, possibly fictional and of which the actual details about are fairly hard to come by, “Umbabarauma” is above all about the thrill of seeing one of the world’s top athletes do something that few others on earth can do: “See how the whole city empties out/On this beautiful afternoon to watch you play” goes the English translation of Ben’s Portuguese lyrics, his backing singers carrying on the hook as he eventually riffs off into a victory lap of his own.

Though a work of art rather than sport, África Brasil is a feat of athletic frenzy all the same, if merely one of many of Ben’s greatest artistic achievements, certainly his most electrifying. It’s neither simply samba nor even samba rock, but a swirling, maximalist fusion of transcontinental and cross-genre sounds, a climactic exclamation point in a career spent redefining Brazilian popular music. Layered on top of Ben’s voice and electric guitar are funk bass, various percussionists, horns, backing singers and the frequent presence of cuíca, the squeaking African/Brazilian drum or “laughing gourd” as it’s sometimes called, its frequent one-note presence providing a kind of symbolic adhesive between the two locales united in the album’s title.

When Ben began playing samba music as a teenager, he found that many of the artists he admired employed a more intricate technical approach, and early on in his career, playing in smaller clubs, he embraced a playing style that emphasized rhythm above harmony. That unique playing style in part helped bridge the gap between classic samba and pop, and in turn brought about some early hits, including “Mas Que Nada,” which was released when he was just 21 years old. But his stylistic approach also laid the foundation for subsequent crossovers into rock and funk—rhythm drove his music, and it’s also what gave it the malleability to bridge his samba roots with so many other styles: rock, funk, jazz and beyond.

Rhythm is everything on África Brasil. There isn’t a moment throughout its 40 minutes that isn’t charged with kinetic energy and ecstatic drive. This is music that’s always moving, both literally and in any other possible sense, its pulse rising and ebbing, but always present and undeniable. Where on his previous albums like 1970’s Forca Bruta and 1974’s A Tabua Da Esmeralda Ben had increasingly embraced more eclectic influences such as rock and psychedelia, África Brasil is unambiguously a funk album, reflecting both the hypnotic groove of Afrobeat as well as the deepest pocket of North American funk and soul alike, as well as the freedom and unpredictability of jazz. “I saw Miles Davis and that was music from the gods,” Ben said in 2013.

“Umbabaraumba” sets the bar high, kicking off with a riff that could keep looping for hours and never lose its paradoxical sense of effortless cool and sweaty intensity. “Hermes Trismegisto Escreveu” grinds even deeper, with bright flashes of horns and an urgent rhythmic strut. The frantic energy and off-the-charts BPMs of the album’s penultimate track “Cavaleiro Do Cavalo Imaculado” feels like being dropped into carnaval while it’s in full swing. And on “O Plebeu,” there’s a breezy call-and-response between Ben, his backup singers, and the twinkling synthesizer that tickles the edge of its otherwise more physical manifestation of funk.

The one song that’s perhaps as widely recognizable as “Ponta de Lança Africano” is “Taj Mahal.” Originally released on the previous year’s collaboration with Gilberto Gil, Ogum Xangô, but in a much longer, more freely improvised version, here it’s more concise and focused, a soaring anthem that centers around its soaring hook. Which wormed its way into wider consciousness for an entirely different, if more dubious reason: Rod Stewart borrowed the melody for his disco hit “D’Ya think I’m Sexy.” As a resolution to the dispute that resulted, Stewart chose to donate his royalties from the song to the United Nations Children’s Fund.

The celebration of Black music throughout Africa Brasil is essentially intertwined with its larger celebration of Black identity—in tune with the emergence of Black pride in the U.S. as well as Afro-Brazilian consciousness. The album in part pays tribute to Ben’s own African roots, his mother having emigrated to Brazil from Ethiopia, and he grew up hearing his family sing traditional songs from their home country. There’s nothing traditional about this set of songs, but they tell stories of heroes that are often left out of history books, like “Zumbi,” a reworking of an earlier track that pays tribute to a leader of a Brazilian quimboa in the 1600s. Or, in the case of “Umbabarauma,” lifting up an ideal rather than a specific figure.

Though revelatory upon its release for both its musical innovations and for being a true masterpiece for Ben, himself, África Brasil caught on a little more gradually in the Northern Hemisphere. David Byrne selected “Ponta de Lança Africano (Umbabarauma)” as the leadoff track for a compilation on his Luaka Bop label in 1989, and remarkably, its video appeared on VH1. In the years that followed, the rise of file sharing networks and eventually streaming found interest in the album spreading among younger generations and those who might never have had access to the album upon its release in 1976. Though it’s steeped in sounds that defined a specific era, it’s joyful in its expression of groove and empowerment. Music that goes this hard simply doesn’t age.

Jorge Ben never did have the pleasure of being a starting player on a winning World Cup team. But releasing a transformational work of Brazilian popular music whose influence echoes after nearly five decades—complete with its own enduring football anthem? Not bad for a consolation prize.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.