Bob Dylan’s Time Out of Mind was the start of something new

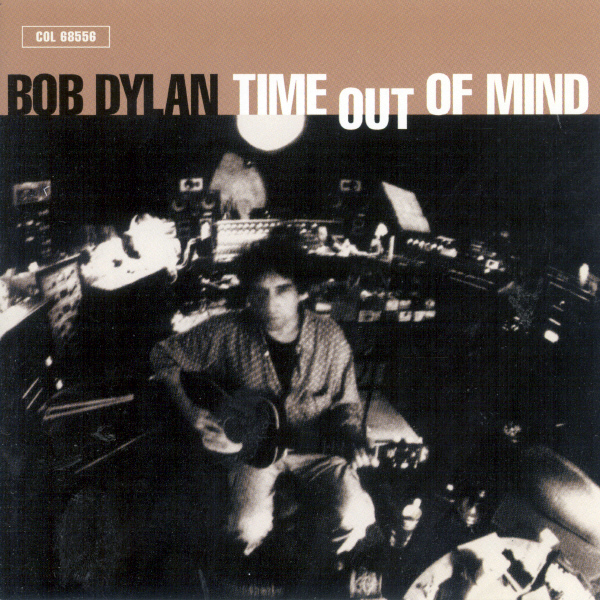

Bob Dylan was only 24 when he introduced “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues,” late on Highway 61 Revisited, by inviting us into a dismal state of mind: “When your gravity fails and negativity don’t pull you through.” The album he made at age 56, Time Out of Mind, is the 70-minute realization of that headspace. Like a long noir, Dylan’s 30th LP is cinematic, pervasively dreary and dripping with style and wit. And as with Highway 61’s nervy electric grit, Blonde On Blonde’s looser Nashville sound, or the mournful open-E guitar that colors Blood On the Tracks, it introduces a fresh aesthetic. It’s the waking despair blues.

The vision wouldn’t have materialized without Daniel Lanois, a big-name producer with an old-school sensibility, renowned for coaxing plush, resonant sounds from hyper-intentional tech. In addition to producing, Lanois played at least three different guitars on the record, both rhythm and lead. He knew what he was in for with Dylan; the two had already worked together on 1989’s Oh Mercy. Though artistically fruitful, their first collaboration had been rocky, and the Time Out of Mind sessions were no less contentious. Dylan is no stranger to studio polish, but he doesn’t make big records the way Lanois does.

Hoping to bridge the gap, Dylan showed Lanois American folk and blues from the ‘30s, ‘40s and ‘50s—Little Walter, Little Willie John, Charley Patton (whose “Down the Dirt Road Blues” directly inspired a track title). These recordings held a fascinating quality Lanois called “depth of field”: “You get the sense that somebody is in the front singing, a couple of other people are further behind and somebody else is way in the back of the room.” And so the artist and the producer struck a deal: they’d aim for an old American sound by way of modern studio finesse.

All the pieces were in place, and there were a lot of them. To record, Dylan sat and played in a corner of the studio with as many as 12 musicians huddled in a horseshoe around him, including Lanois. These conditions give the album a crowded, organic feel. Paradoxically, it sounds like Dylan and Lanois were only able to evoke this much raw isolation by layering as many live instruments as they did. Organist Augie Meyers comes up strongest of all. As Dylan borrows from early 20th century American folk and blues, suiting them to his dour ends, Meyers injects style and flair at the right times. Without his staccato pulse “Love Sick” would have no business in a Victoria’s Secret ad, and “Million Miles” wouldn’t be such a soundscape. On “Standing In the Doorway” and “Highlands” he’s less assertive but just as essential. He even makes “Can’t Wait” sound like a Doors song.

There’s not a weak song here, but the album’s best run lasts three songs and starts with the third track. “Standing In the Doorway” is achingly beautiful and open-hearted, elevated by the arrangement in 6/8 time (before recording the version that made the record, Lanois asked Dylan if they could try it with a “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” feel). “Million Miles” is a gutting blues shot through with signature Dylan wit: “Well, I don’t dare close my eyes and I don’t dare wink / Maybe in the next life I’ll be able to hear myself think.”

But “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven” is the showstopper. Like “Tangled Up in Blue” it’s an American traveling song: through high muddy waters, down the river, by buggy and by train, among people waiting on platforms with their hearts beating like pendulums on chains. Between feverish verses Dylan plays his only harmonica on the album, so processed and pained it sounds like an electric violin. This is one of Dylan’s best songs, the gut-wrenching cry of a man realizing how far he’s strayed, desperate to lay down the load. “Not Dark Yet” hits the same emotional notes with even stronger words. Dylan poignantly shifts between layering metaphor onto his struggles (“I’ve still got the scars that the sun didn’t heal”) and confessing them outright (“Sometimes my burden is more than I can bear.”) By the end, “Every nerve in my body is so naked and dumb / I can’t even remember what it was I came here to get away from.”

Like “Desolation Row” on Highway 61, “Highlands” hammers this mood home with fewer instrumental parts, many more verses, and the story of an ambiguous search for an ill-defined place. At 16 minutes it’s Dylan’s second-longest song to date, recently eclipsed by the equally indulgent and even more brilliant “Murder Most Foul” from 2020’s Rough and Rowdy Ways. But unlike that odyssey, in which he weaves a surreal myth about the JFK assassination into a recitation of the great names across American music history, “Highlands” is an “epic” of everyday inconsequences and alienation. “Feel like a prisoner in a world of mystery,” Dylan sings, and goes on to relate a seemingly pointless story of a strained interaction with his waitress in Boston. When he’s done he “steps back outside to the busy street, but nobody’s going anywhere.” Neither, as it turns out, is Dylan—even though his heart’s in the highlands. In other words, not much has changed by the end of the record: “Same old rat race, life in the same old cage.”

Thankfully, all that fatalism was a feint. Above all else, Time Out of Mind was the start of something new for Dylan. From then on, his music would consistently borrow old songforms and show a fascination with cataloging early 20th century tunes. But he would continue to explore texts from even earlier—especially the Old Testament. The phrase in the chorus of “Love Sick,” “sick of love,” can be taken to mean “tired of love.” On the other hand, the King James Bible translates Solomon 2:5 as: “Stay me with flagons, comfort me with apples: for I am sick of love.” Here the phrase has quite a different meaning: sick with love. In this context, we can see the condition Time Out of Mind really shows us: having an abundance of love, hauling enough of it around to make you sick. Holding onto so much love that you can’t help but blot everyone and everything else out.

The most culturally enduring song here, “Make You Feel My Love,” has been the most often criticized for being out of place on the record. But it works as a love song in Dylan’s fish-eye lens greyscale reality, loaded with far more desperation than tenderness. The only settings Dylan mentions are “raging, rolling seas” and “the highway of regret.” And “I’d go hungry, I’d go black and blue, and I’d go crawling down the avenue / No, there’s nothing that I wouldn’t do to make you feel my love” aren’t tender words, no matter how many streams Adele racks up. “Make You Feel My Love” seems destined to join the ranks of “Will You Love Me Tomorrow,” “Every Breath You Take,” “The One I Love”—ubiquitous “love songs” with huge gulfs between perception and meaning.

This isn’t to suggest that “Make You Feel My Love,” or any song here, invites a ready-made interpretation. It wouldn’t be a Bob Dylan song if it did. Whatever sonic environment he finds himself in, Dylan understands the power of suggestion through imagery. Church bells ringing in the yard, scars the sun didn’t heal, memories thrown in a ditch so deep, cold irons that bind. He deals in simple language to save room for the ineffable. Following him isn’t a comfortable journey. But Time Out of Mind glows with the hidden grace to keep us coming back.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Casey is a writer who lives and breathes music. He’s written about it for Spectrum Culture, Grandma Sophia’s Cookies, Plaze Music and WTJU.

It’s naked and numb, not naked and dumb. You’ll probably agree “numb” makes a lot more sense.

Solid analysis on your part.

Thanks.