‘The River’ at 40: Bruce Springsteen vs. Real Life

Ant Farm was an artist collective founded by two San Francisco architects in 1968. Their work manifested in various forms and staged events, like the time they drove an outfitted Cadillac into a wall of burning televisions in the Cow Palace parking lot on Independence Day in 1975.

Upbraiding consumerism was Ant Farm’s imperative. The British architectural resource Spatial Agency says that they pursued a direct contrast to the “heaviness and fixity of the Brutalist movement” with more mobile, easy-to-assemble buildings, a comment on the shifting symbology of American optimism.

Their most famous work remains the Cadillac Ranch, an installation originally commissioned by a wealthy and controversial billionaire who simply wanted to build something that would piss off his neighbors in Amarillo, Texas. Ant Farm bought ten used, inoperative Cadillacs and buried them up to their windshields into dry Texas ground, positioned at about a 115° angle.

The Cadillac Ranch went up in 1974 and is still intact today, just a couple of miles from its original location. Over the years the submerged Cadillacs, once representative of the regal pursuit of American comfort, luxury, and mobility, have been scrawled on and painted over by thousands of visitors. The creators and keepers of the Cadillac Ranch were fine with that.

***

Around the time the real-life Cadillac Ranch went up, Bruce Springsteen was working on his breakthrough third album Born to Run. After two albums in which he told youthful stories with chimerical wordplay and imagery, Springsteen focused his narrative for eight stories about the new intoxications of adult freedom.

Born to Run was a headlong rush of possibility, an album that celebrated anticipation in tracks like “Thunder Road” and the title cut. Even its melodramatic heartbreakers, “Backstreets” and “Jungleland,” felt like net-positive discoveries of the range of human experience—even sideswipes depicted chance and new options. Born to Run was a reset for both Springsteen and rock ’n’ roll.

Three years later Darkness on the Edge of Town reached the other end of that joyride. Springsteen addressed the twilight of adulthood, the measures one takes to escape numbness and breakdown: the daily grind of “Badlands” and “Factory,” or the erotic grappling in “Candy’s Room” and “Prove It All Night.” He acted out in danger or recklessness in “Racing in the Street” and “Streets of Fire,” to unknown ends. Darkness was sonically darker than Born to Run, with closer-to-the-bone production and edge.

The two albums weren’t extreme opposites, but they depicted two vastly different sides to the same myth. Born to Run was a hero’s odyssey; Darkness on the Edge of Town a hero’s trials. Both took place just a few yards above the earth: Born to Run in a dream state, Darkness in a mild state of panic.

For his next trick, Springsteen corralled all those elements and brought them back to earth. The Cadillacs headed to the suburbs.

***

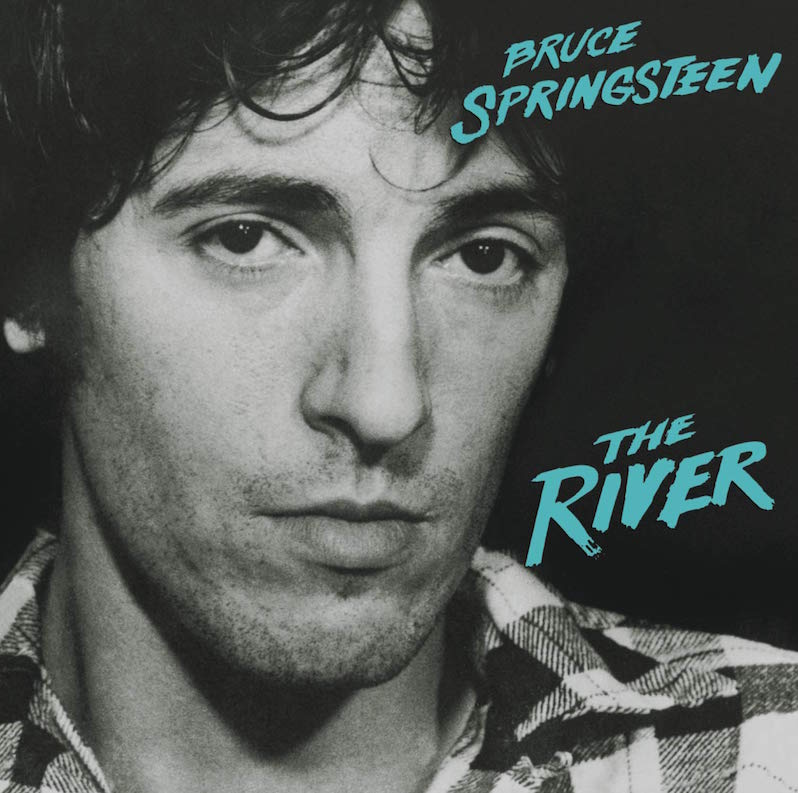

The River, released 40 years ago this month, isn’t a chapter-by-chapter story of a single person. That would make it a rock opera. If there was one reason Bruce Springsteen was put on earth, it was to save us from rock operas. Some of us didn’t make it.

But it’s allowable to interpret Bruce Springsteen’s The River as a single life’s chronicle because it’s structured like a novel. Springsteen began investigating literature in earnest a bit before The River came out. “I skipped most of college, becoming a road musician, so I didn’t begin reading seriously until 28 or 29,” he told the New York Times in 2014. “Then it was Flannery O’Connor; James M. Cain; John Cheever; Sherwood Anderson; and Jim Thompson, the great noir writer.”

It’s the connection with O’Connor, the trenchant writer of the South, that informs a lot of the characterizations on The River. Her short stories (one of which is titled “The River”) are snapshots of commonplace, even banal events in slow-moving, everyday lives. Some characters exit the stage with only the barest hint of a perspective change; a few explode in unaccountable, blind rage; some quietly pass by or pass on.

Springsteen acknowledged O’Connor’s influence on his work: “There was something in those stories of hers that I felt captured a certain part of the American character that I was interested in writing about.” To do that, Springsteen scaled down his narrative. There aren’t any blow-by-blow tales in the mode of “Rosalita” or “Jungleland” on The River, but there are plenty of deep descriptions of characters reacting and adjusting to a variety of static situations.

At the same time, Springsteen enlivened his recorded sound. E Street Band guitarist and resident garage rock expert Steven Van Zandt collaborated with Springsteen and his longtime producer Jon Landau to replicate the energy of the unit’s fabled live shows. The result was a reverberant epic about common human struggles—equal parts Woody Guthrie, Nuggets, Mitch Ryder, and Aaron Copland.

Springsteen may have stripped down his storytelling on The River, but his portraits got deeper and wider. His characters from Born to Run and Darkness were ones everyone recognized. The characters on The River were ones we knew.

***

The dramatic context of The River may well have been unthinkable to the heroes who bore Born to Run’s audacity and Darkness’ distress. Instead of tooling around open roads and hitting dead ends, The River’s narrators contend with daily errands, take whatever indulgences they can get, play chicken with conformity, and ultimately make bargains just to stay alive. These are more minute and precise situations, not the standing stones Thunder Road and Candy’s room represented. They’re where Springsteen scales his idealistic vistas into a more navigable, realistic path.

The characters don’t go quietly. The River constantly asks whether survival can ever repay (“To settle down is to settle without knowing the hard line that you’re settling for,” sings Bruce in “Jackson Cage”). The characters are suspended in the neutrality suburbia advertises. From their vantage points they see portals leading in two directions: the light of their rebellious years, and the darkness of certain mortality. They’re pulled by the magnetism of both as they fight the gravity that’s favored to win.

The question Springsteen poses on The River isn’t whether avoiding these extremes is possible, but whether it’s worth it. He doesn’t entirely answer the question. In fact, he’d continue to examine it on his next three albums (Nebraska, Born in the U.S.A. and Tunnel of Love).

***

Then, of course, there’s the car. The River’s characters may live in places with more regulated speed limits, but they didn’t turn into power walkers overnight.

The mythology of the automobile in Springsteen’s work is undeniable, to the extent that Prefab Sprout’s Paddy McAloon wrote a gentle criticism about it called “Cars and Girls.” (Springsteen reportedly liked the song. McAloon swore he meant no offense.) But there was a lot more to Springsteen’s car imagery than just fun, fun, fun.

The automobile was America’s first emblem of post-war promise. The interstate system stood for a quick way out to wherever people wanted to go. The act of motion informed Springsteen over the entire course of his 1975-80 triptych, and where he was going was too demanding for a Vespa.

On The River, the car represents both tedious responsibility (“Sherry Darling”) and the arrival of lust (via the “Hong Kong special” — a misidentified compact — on “Crush on You”). Sides 3 and 4 especially depend on the vehicle: the surest conveyance to whatever fate the characters deserve. It’s the singer’s last shot at rebellion (“Ramrod”), oblivion (“Stolen Car”), redemption (“Drive All Night”), or death (“Cadillac Ranch”). On “Wreck on the Highway” it plays a part in the final takeaway: Life can be usurped from you at any time with little warning, so in your daily affairs it’s in your best interests to err on the side of survival and keep your insurance current.

***

Rock ‘n’ roll was around 25 years old when The River was released. It was still positioned as rebel music. But it was also starting to sense a need for its preservation. Bob Seger had already pined for “Old Time Rock and Roll” in 1978, only two years after rock and roll was legally able to drink.

Springsteen, who outspokenly embraced the derelict fury of punk, might have known that rock and roll had issues to resolve if it was going to become a growth industry. That’s why the trilogy of Born to Run, Darkness on the Edge of Town and The River is so effective. You heard hallmarks of classic rock ‘n’ roll in all of them, but they told a distinctly modern story in three relatable stages: hope, despair, and uneasy compromise.

Springsteen’s energy for all three phases was unstoppable. By the end of the The River, it had been channeled in as many different moods and tones as it could, from joy to rage and acceptance. The River was the culmination of Springsteen’s most heroic era, but unlike the tragic rock mythology Neil Young sang about (or the one the Sex Pistols lived), he’d found a place for the hero to catch some actual rest. If that’s a compromise on paper, it doesn’t feel like one on the record.

Like characters in many of the best 20th century American novels, the The River’s heroes must fight through the mundane as much as the catastrophic. They almost lose their heroism in the process but end up quietly keeping it. Ten half-buried Cadillacs later, they realize that’s how life usually works out.

The River Side by Side

Side 1: Inevitability

Springsteen’s old characters may have idealized the lone walker, but The River’s first track blows holes in that facade. “The Ties That Bind” strips the heroism out of solitude. It’s never voluntary, and it denies reality; it looks tough, but it’s not brave: “You walk cool, but darling, can you walk the line?” Of course, reality can also be boring as hell, as in “Sherry Darling” where Bruce is fed up with having to schlep his slacker mother-in-law to the welfare office, or in “Jackson Cage” where the day-to-day grind in the suburbs seems pointless to fight: “Just crossed swords on the killing floor.” All three songs wrestle with fate: when to accept it, when to fight it, whether to give up.

The last two songs on the side seek initiative. “Two Hearts” brings up the same ironman exterior as “The Ties That Bind,” the fact that blind determination is usually an unsettled state: “Alone buddy there ain’t no peace of mind.” Finally on “Independence Day” the singer has to take action to break away from the inevitability his father represents (“They ain’t gonna do to me what I watched them do to you”) and head toward a reality he’s been trained to mistrust, but now understands as natural transformation—another inevitability (“There’s just different people coming down here now and they see things in different ways/And soon everything we’ve known will just be swept away”).

Side 1 lays out the preordained nature of family, love and change. The rest of the album is a bargaining session between people who want to escape or manipulate that inevitability.

Side 2: Desire

The characters on Side 2 have all come to realize, if not accept, the ties that bind on the first side. Now they push the boundaries of their commitments to see what they can get away with.

The simplistic guy in “Hungry Heart” cashes in an uneventful home life in Baltimore to pursue a vague something in a crappy small-town bar. It doesn’t work; the cycle restarts. Pressed for a response, he shrugs and says, “Everybody’s got a hungry heart,” while Spector-esque dream pop cascades around him. Like “Born in the U.S.A.,” “Hungry Heart” is more than the simple crowd-pleaser it seems on the surface. Springsteen’s really asking if the thrill of quick abandon justifies the longer emptiness. It was his first Top 10 single.

“Out in the Street” and “Crush on You” are ragers that chase after relief, lust, and continuance of the party. “You Can Look (But You Better Not Touch)” inserts a few warnings, but they’re mainly comic (“I knocked over a lamp, before it hit the floor I caught it/Salesman turns around, says ‘Boy, you break that thing, you bought it’”). The Tex-Mex “I Wanna Marry You” finds the singer trying to woo a single mom, turning the act of settling down and being more responsible into a desire unto itself. But like “Hungry Heart,” you’re not sure the guy’s thought this whole thing through.

“The River” is more of a pivot to the very dark contents of the rest of the record. The situation it describes—a teen pregnancy, a quickie marriage, early consignment to the factory life—are by-products of a desire the singer can’t quite abate (“Now these memories come back to haunt me/They haunt me like a curse/Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true/Or is it something worse”). The river is where his youthful fantasies ran amok, but in truth moves in one and only one direction. It’s not going to change course just because he’s jumped in. It’s taking him to the same place it takes everyone else.

Side 3: Disappearance

You could also call Side 3 the “Death” side. I was tempted but for the presence of its third song. It starts off with “Point Blank,” Springsteen’s bleakest song up to that point. The singer’s former lover is a shadow of herself, having endured every muted disappointment adult life has to offer and not recognizing her past.

Positioned right after “Point Blank,” “Cadillac Ranch” is almost a cruel joke, another misdirection in the vein of “Hungry Heart” that should have been the album’s second single. It satirizes the reckless release of songs by people like Eddie Cochrane, listing a roster of speed freaks (the automotive kind) all happily tearing down a desert highway to their imminent demise. Only at the end do you realize the singer himself is still in mourning-slash-denial over someone else’s departure. “I’m a Rocker” is the only song on the album that’s truly misplaced if you’re buying this whole narrative thing I’m trying to sell you. It’s comic relief about rescue, so it’s not a total stretch.

“Fade Away” (which was the second single from the album) is one of Springsteen’s most vulnerable songs, dealing with the gradual disappearance from a lover’s life, leading to a probable diminishment of his own. In “Stolen Car” the loss of love is presented as something criminal: He feels his emotions gave him some sort of responsibility, but it couldn’t sustain itself with all the struggles. So now he gets to feel the guilt of freedom: “I’m driving a stolen car/Down on Eldridge Avenue/Each night I wait to get caught/But I never do.”

Side 4: Redemption

The redemption side works because the hero’s been materially vacated of his heroism. It’s not coming back, not in the same form as before. If it does come back it won’t do so cheaply. There are no winning lottery tickets or raptures or anything like them. So Springsteen takes the novelist’s way out.

It starts with him still going down what’s probably an ill-chosen path: “Ramrod” is a not-so-subtle pursuit of lust, with a title that’s the most direct phallic symbol he ever put on record. But there’s a twist when he talks about “a cute little chapel nestled down in the pines.” He’s desperate for something more elevated that sex will unlock, hoping it shows up as a by-product of recklessness. That’s a universal impulse. Everyone feels it at least once.

“The Price You Pay” is at once an admission of the whole reality that underlies the entire record and one last defiant strike against it: “But just across the county line, a stranger passing through put up a sign/that counts the men fallen away to the price you pay/And girl before the end of the day/I’m going to tear it down and throw it away.” Lesser albums would end with this thought.

But Springsteen knows there’s more to settle. “Drive All Night” is a rock gospel that unfolds like “Madame George” from Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks—taking its time, ascending in slight registers with every realization Springsteen makes, through a Clarence Clemons sax solo that pushes him toward his final acclamation. The band slowly builds until it’s full volume except for Max Weinberg’s steady, gentle rimshots. At the end the singer can only express himself in fractured pleas: “You’ve got my love, girl, you’ve got my love/Through the wind, through the rain, the snow, the wind, the rain/You’ve got, you’ve got my, my love/Oh girl, you’ve got my love/You’ve got my love/Oh girl, you’ve got my love/You’ve got my love/Oh girl, you’ve got my love/You’ve got my love/Heart and soul/Heart and soul/Heart and soul/Heart and soul.”*

“Wreck on the Highway” is the finale, and a song many listicle makers cite when writing pieces called “The 10 Most Depressing Bruce Springsteen Songs.” It’s stark enough: the narrator comes upon a fatal accident on an untracked road, away from civilization. The police haven’t arrived yet. “I seen a young man lying by the side of the road/He cried, ‘Mister, won’t you help me please?”’ The ambulance finally arrives and takes the kid away. Springsteen doesn’t specify if the victim survives, but he thinks about how it might feel for someone to hear from a state trooper that their loved one is dead. He goes home to his sleeping wife, climbs into bed and holds her. Next stop: Nebraska.

—-

*(Compare with this break in Morrison’s “Madame George”: “And the loves to love to love the love/Say goodbye, goodbye, goodbye/Say goodbye, goodbye, goodbye, goodbye to Madame George/Dry your eye for Madame George/Wonder why for Madame George/The love’s to love, the love’s to love, the love’s to love/Say goodbye, goodbye/Get on the train/Get on the train, the train, the train/This is the train, this is the train/Whoa, say goodbye, goodbye, goodbye, goodbye/Get on the train, get on the train.”

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Paul Pearson is a writer, journalist, and interviewer who has written for Treble since 2013. His music writing has also appeared in The Seattle Times, The Stranger, The Olympian, and MSN Music.