Nebraska: How Suicide influenced Bruce Springsteen’s dark masterpiece

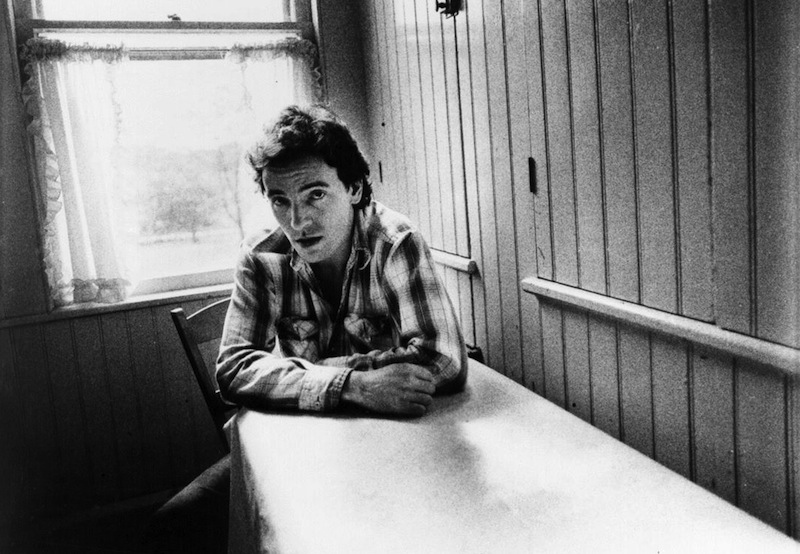

At the peak of Bruce Springsteen‘s Born in the U.S.A. fame in 1984, he appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone, clad in signature denim and leather, and a red bandana wrapped around his forehead. He looked every bit the rock star behind the year’s best-selling album, and over time eventually sold 15 million copies in the United States. But in another light, without the knowledge that Springsteen and the E Street Band had a commercial lock on 1984, he might look a little bit different—like a punk rocker, perhaps. Truth be told, he and Joe Strummer might have been body doubles in a lineup, and Springsteen had rubbed elbows with punk royalty before. He wrote Patti Smith’s hit song “Because the Night,” and even shelved his own version for decades because he liked hers so much better. But in the actual cover story, penned by a pre-MTV Kurt Loder, he affirms his cred by declaring his admiration for Suicide‘s dark, minimal self-titled synth-punk debut and, in particular, the band’s 10-minute horror drone, “Frankie Teardrop.”

“That’s one of the most amazing records I think I ever heard,” he says when asked about it. “I really love that record.”

That sentiment might not entirely square with the anthemic heartland rock of Born in the U.S.A., one of Springsteen’s biggest and most accessible albums (and, indeed, one of his best while we’re on the subject). But there’s considerably less cognitive dissonance in the context of its immediate predecessor, 1982’s Nebraska. For a rock icon of Bruce’s stature, even 34 years ago, following up a colossal double-LP collection of haunted roots rock like that of The River with a set of chilling, sparse and mostly self-recorded demos was a bold move. That a gothic Americana album was released in the New Wave era—on a major label—now seems, well, sorta punk.

One of the notable inspirations on the album, in fact, was Suicide’s 1977 debut. Springsteen became a fan of the band early on, despite their own reputation for confrontational performances—met by equally confrontational audiences, as one Brussels show opening for Elvis Costello would prove. In 1980, Springsteen crossed paths with Suicide, as they were each recording new material, which convinced singer Alan Vega early on of The Boss’ genuine appreciation for their music.

“We first met Springsteen in 1980,” Vega said in a 2014 interview with the New York Post. “He was recording The River and we were recording our second album in New York. … Then we had a playback meeting for our album. There were three or four big shots from our label, and Bruce was there, too. After we played the album, there was deathly silence . . . except for Bruce, who said, ‘That was fucking great.’ He made a point of telling us how much he loved us.”

It’s hard to over-emphasize the significance of one of rock’s biggest artists championing the underground innovators. Suicide most certainly left their mark on electronic music and punk, the drone of Martin Rev’s organ and the alternating croons and wails from Alan Vega created an entire synth-punk genre unto itself, influencing artists ranging from fellow Moog buzzers The Normal to contemporary artists such as TV on the Radio or Algiers. There wasn’t a lot to their sound—simple melodies, expressive vocals and drum-machine beats—but it made a massive statement, reflecting stories about street people or cult superheroes, or in their most infamous song, a harrowing story of a laid-off factory worker and Vietnam vet who kills his family and then himself, rendered with blood-curdling screams and terrifying use of empty space. At heart, though, Suicide and Springsteen both came from the same influences—the early rock ‘n’ roll of Gene Vincent, Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison and Elvis Presley. “I never heard anything avant garde,” Vega said of Suicide’s music. “To me it was just New York City blues.”

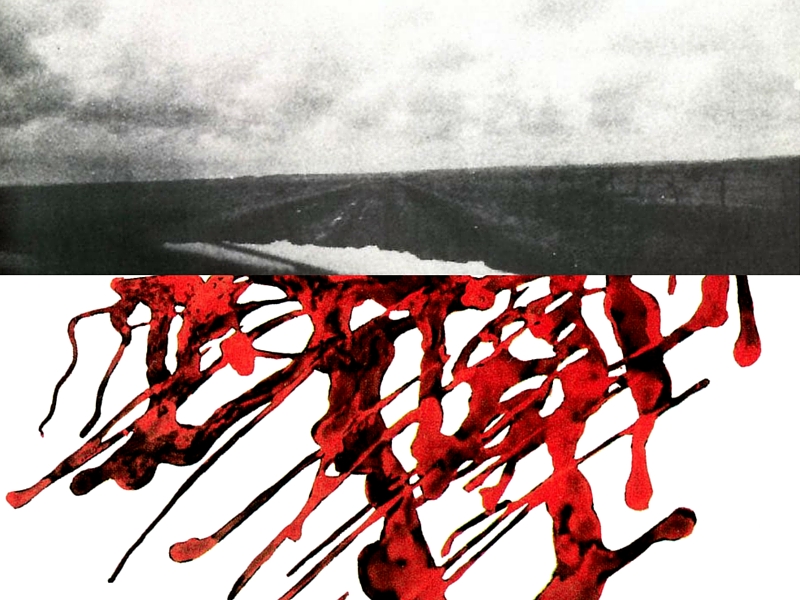

Nebraska and Suicide’s debut album don’t necessarily sound that close on cursory listen—Springsteen’s album is entirely composed of recordings played on acoustic guitar—but they have similarities that go deeper than specific instrumentation or BPMs. Just as Suicide’s album is splattered with blood on its iconic cover design, Nebraska has a bleak and violent nature, depicting a portrait of America at its most desperate and hopeless. It’s a haunting and autumnal album, the sort of recording that only makes sense late at night and with jangled nerves. It’s a rustic and barren landscape riddled with villains, ghosts and people driven to their wits’ end. The title track is actually about a serial killer, Charles Starkweather, who murdered 11 people in Nebraska and Wyoming, while standout ballad “My Father’s House” actually features a stark backing of synthesizer, not unlike that of Suicide’s sparsest ballads.

“Frankie Teardrop” is the song that looms largest over Nebraska, informing both the sound of the record and its themes. Springsteen’s “Johnny 99” more or less follows a similar narrative, in which an auto worker loses his job and ends up committing murder as a result. Yet “Johnny 99” is upbeat, even oddly fun by the standards of the album, sounding more like “Rocket USA” than “Frankie” itself. “State Trooper” is a different story. It’s essentially “Frankie Teardrop” translated into a dark folk song, the acoustic strums create a heightened tension that breaks when Springsteen unleashes a series of unexpected yelps nearly as startling and unsettling as those Vega utters in his own twisted masterpiece. The similarities go deep enough that, after hearing “State Trooper,” he thought it was his own song.

“I remember walking into my label just after it came out,” Vega said after hearing “State Trooper” for the first time. “I thought it was one of my albums that I had forgotten about. But it was Bruce!”

The version of Nebraska that was released wasn’t necessarily the one that was originally intended as the finished product. Making big rock ‘n’ roll records was Springsteen’s bread and butter, and he even convened with the E Street Band to record an electric, full-band version of the album. And by the band’s own accounts, it rocks pretty hard. Given the way that Bruce has been releasing archival material to coincide with 35th anniversary reissues of his classic albums, it’s likely only a matter of time before the recordings end up surfacing, though for the time being it remains one of rock music’s holy grails.

“The E Street Band actually did record all of Nebraska and it was killing,” E Street Band drummer Max Weinberg said in a Rolling Stone interview. “It was all very hard-edged. As great as it was, it wasn’t what Bruce wanted to release.”

There aren’t many records in Springsteen’s catalog that bear much similarity to Nebraska, the most likely counterpart being 1995’s The Ghost of Tom Joad. Yet his love and appreciation for Suicide’s music has remained a constant throughout his career. He’s said they belong in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and he even covered the band’s classic song “Dream Baby Dream” on 2014’s High Hopes. And after Alan Vega died this weekend, Springsteen offered a touching eulogy and reflection on his importance and influence: “The bravery and passion he showed throughout his career was deeply influential to me. I was lucky enough to get to know Alan slightly and he was always a generous and sweet spirit.”

Springsteen’s right about Vega’s generosity. Without it, not only would we not have Suicide’s brief but essential discography, we wouldn’t have Nebraska either.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.