Working through grief and healing through Camel’s ‘The Snow Goose’

And now, with a potentially contentious figure to be declared prog out of the way, it’s time to return to the calmer waters of the classics.

On paper, there are more immediately obvious figures that come to mind. Opening with the dual gambit of King Crimson and Yes was not an indeliberate act; regardless of more adventurous and controversial terrain that can be covered, those two undeniably lay the foundation of what we mean when we talk about progressive rock. To a certain perspective, the next most obvious place to venture would be Pink Floyd. Their workmanlike approach to the genre, emerging directly from the London underground of the psychedelic club scene in the ’60s, not only made them the defining group for space rock as a whole but also generated one of the most universally beloved approaches to prog and music as a whole of the 20th century. We will come to them in due course, but unfortunately it is precisely that element of universal acclaim that makes them less interesting to approach so soon. They’re a profoundly legendary group and, as a result, it unfortunately becomes somewhat tricky to have an approach for them that actually gains us any new insight or ground.

After the legendary Pink Floyd, the next most obvious would be Genesis. They’re at once beloved and reviled, with the particular cited reason for either being different depending on who you ask. For some, they are a whip-smart and sonically adventurous pop group, one that wields prog acumen and technical proficiency to create lush and imaginative pop-rock but could only arrive at this after years of aimless noodling and frankly dull meandering. For others, it is precisely the inverse, with a lush and panoramic cinematic vision of the potential pastoral power of progressive rock, intertwining classical music, English folk and psychedelic pop into a vast and cosmic vision. Genesis are certainly a tantalizing group for a project like this, a true perfect fit: but following King Crimson and Yes with Genesis in the chapters on classic prog would again sadly feel just a little bit too on-the-nose, so perfect as to almost feel lazy. Genesis deserves better than that sort of appearance, and so examining them in this format must be delayed.

After a great deal of thought attempting to balance the urge toward covering the obvious versus shooting to the relatively obscure, eventually a perfect path between the two appeared: Camel. They’re a curious band, largely due to how they refused to sit properly within any expectation. As a commercial entity, they were moderately successful in their heyday of the ’70s and still manage to produce a pull now; despite this, functionally none of their music seems to have survived in the archivist worlds of classic rock radio or the like. Within the world of prog, they are a well-known entity, a group whose span from their debut on to 1978’s Breathless are considered mandatory listens within that world. Meanwhile, to the world beyond, it seems most often like they might as well not exist for all that you might hear of them. Their music, especially on those classic ’70s records, manages to simultaneously sound precisely like what an on-paper description of prog cliches might assemble to and, at the same time, like almost no other prog band active at the time, save perhaps a sidelong and infrequent similarity to Genesis. It is a bizarre and contradictory space that they inhabit, at once producing not one but several records which are considered landmark recordings within the genre but then, beyond its walls, seeming to fade away to nothing, while groups both larger and smaller than them manage to find penetration and interest

The solution to this bizarre paradox seems to arrive when examining Camel’s general approach to prog. It is tempting to get overly taxonomic about progressive rock at times, to overly pathologize and describe in colorful words things like its tendency toward high-contrast pairings of sections or tones, the way odd time-signatures and brief flashes of virtuosity (not to mention that ever-present Frank Zappa influence in abstruse and dense intervallic solos) can produce a profound angularity. The problem is that, once you nail down one of these elements and define it as essential to prog rock, another seems to leap up to contradict you. If angularity is definitive, what then of the sweeping epic strings of the title track of “In the Court of the Crimson King” or the spacey passages of Pink Floyd? If you incorporate all of these, how then do you account for the strong pop-driven and even verse-chorus-verse structure of “Roundabout”? Hell, even “Close to the Edge,” perhaps the defining epic of the genre, lives in a verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge-chorus-chorus structure, merely blown out to macroscale and maximum length.

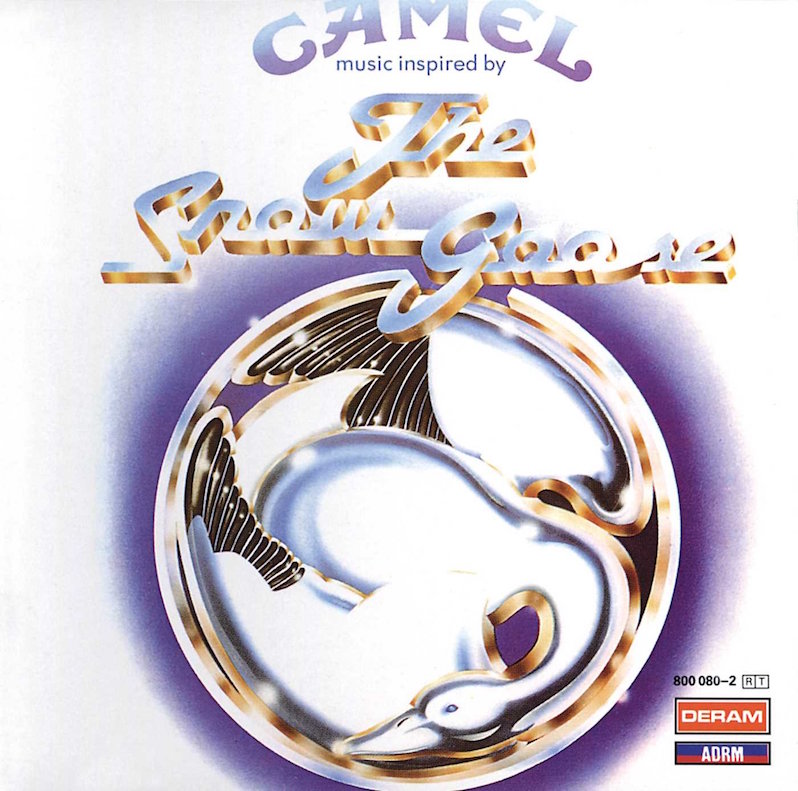

Still, there is an imagistic association I have with progressive rock that Camel seems to cut against. Most prog tends to have a sonic tenor that manages to replicate some essential aspect of its cover art; or, perhaps, it is a relation in the opposite direction, an image drawn in part from what is put on tape. Ultimately, however, this tends toward either a sharpness and crenelated definition, like the line-heavy and detail-rich covers of fantasy and science fiction novels, or else a kind of polyphasic haziness, be it the paradoxical fusion of the sharp and the abstract in post-modern design-centric covers such as the greats from Hipgnosis or the general spacy, psychedelic, oceanic or pastoral treatments you might find elsewhere. Camel, meanwhile, seems proudly oblivious to these kinds of imagistic associations. Their approach to prog has the unique sensibility of feeling more like watercolors, the center of their sounds and thoughts definable but still streaked with the white of the page beneath, the edges rounded and fading rather than sharp and delineated, with any given thought or sound or melody seemingly infinitely capable of transparently overlaying atop what came before like the gentle overlapping of colors. Listening to their records is less like going on a heady psychedelic journey to the center of the mind, feels absolutely agnostic to the tendencies toward lightly appropriative mysticism and deep intellectualist ruminations. Instead, the tenor is closer to watching The Snowman, the half-hour animated film from the early ’80s that has since become a Christmas classic. There is a tremendous capacity to grip Moonmadness, one of Camel’s most seminal releases, stare at that gentle white wintry plain caked so deep in snow and the gleaming near whiteness of the sun’s bleached rays and hear in your head, inexplicably, “Walking in the Air,” that now-quintessential song from the film. There is an uncanny spiritual resonance between Camel’s classic works with their deliberate desert/heat-haze mirage-like sensibility and the similar haziness and fibrousness of watercolors against white paper seen in that film, almost as though it (and the book it was based on) were produced after months and months of hours-long binges of Camel’s music.

Of all their albums, none embodies this ideal as much as The Snow Goose. The other records of Camel’s 70s-era peak wavered in their full commitment to this aesthetic, overlapping as it does with their similar heat-haze psychedelia. The group’s material from I Can See Your House From Here onward into the ’80s would progressively sharpen their sound into a tight and snappy prog-tinged AOR, not unlike what Gentle Giant, Saga and others would do in the same era, all in an attempt to remain relevant in the changing tides of the musical landscape. Slowly but surely the band would collapse inward over the years until finally only Andy Latimer remained of its golden age lineup. The early ’90s would see Camel return to their more traditional sound, much like how groups like Yes, King Crimson and others were doing the same. The group would produce four records from 1991 to 2002, each settling deeper and deeper into their previous desert and heat-driven sense of psychedelia and prog. Latimer never led a band or recorded an album that was an outright failure, though there certainly were records along the way that were perhaps a bit less immediately satisfactory as others. Those that succeeded tended to do so not by shifting with the winds of time (a technique that admittedly brought success and creative excitement to some of their peers) but rather those that dug deepest into that elliptical sensibility that felt so often more like holding a wordless children’s book with pages splashed with blobby and impressionistic watercolors rather than the stiffened AOR that would come to drive things. The Snow Goose is the very center of Camel and of Latimer, their decoder ring, an unvarnished and untinted image of their interior identity, as transparent and vibrant as viewing a beating human heart through clear glass.

***

Like almost everyone of my generation, my first exposure to Camel was through Opeth. This thought is substantially less shocking now. Opeth’s shift to playing traditional progressive rock full-time was by now almost a decade ago, with four albums in the style under their belt from the current iteration of the group. For those that never read an interview with the group and knew nothing of either band prior to now, the notion that one contemporary progressive rock band would be deeply influenced by a classic of the genre, one beloved by fans of the style even if they struggled to break out far beyond that, would feel almost immediately self-evident. But, as many know, Opeth was not always a contemporary progressive rock band. Or, rather, they were, but this was the spice to their music and not the main course itself. Opeth were, of course, a death metal band.

Not only was vocalist Mikael Akerfeldt breaking the norm of death metal, citing openly in interviews with publications big and small the influence of a flute-drenched melodically-driven prog rock band on his playing and composing. This was also in the ’90s and early 2000s, a period where progressive rock was still widely shunned by audiences and openly spurned and rebuked by critics. This was the era where Radiohead, on releasing OK Computer, as clear a contemporary prog record as you could possibly make, would openly get mad and yell at an interviewer for daring compare their new record to Pink Floyd and ask after possible influence; on their progressively more adventurous and avant-garde future records, they would again and again repeat the same, acerbically spitting back that they were more hip than to listen to sequin-caped losers. (Radiohead would, incidentally, finally admit the obvious some time later.) Akerfeldt was breaking a number of unspoken but heavily enforced rules both within extreme metal culture at the time and the broader musical world. Not only was he openly praising something that wasn’t a heavy-as-hell grime-covering demo from a South American, northern European or east Asian obscurity, not only was it a progressive rock band, but one of the groups that had recorded an instrumental concept album based on a children’s book. That Akerfeldt was an open and avowed fan of Porcupine Tree was one thing; they were a young band as well then, rising in acclaim within the world of critics and listeners alike by being a decidedly modern band. (It helped that Steven Wilson, much like Radiohead, staunchly insisted he wasn’t making progressive rock.) Something like openly citing Camel was almost absurd on its face.

Like many people in the early 2000s, I was deeply taken by Opeth. They were for a very long time my favorite band in existence; even now, I only really consider them retired from that position because I think I’ve heard too much to have one clear and obvious answer to that question. Opeth were partly so big for me because they were the band that thrust “progressive rock” as a notion into my hands. It was only after going back to the forum where I’d first learned of them, asking what in the world I was listening to and why it reminded me so much of Pink Floyd and Mr. Bungle and Tool and Radiohead in its adventurousness, that I was then told about the genre existing at all. I was given a shortlist of bands to look into: Yes, Genesis, Rush, etc. Regrettably, I took my time in actually pursuing those leads. In part, it was because I simply loved Opeth so much, fresh in the wake of the release of Blackwater Park and soaking up everything that had come before, feeling often like I had more than enough to dig into with that one band alone. But a portion of that hesitation was in my association of those other groups, being a young rockist snob who turned his young nose up at things like “Owner of a Lonely Heart” and “That’s All” and “Closer to the Heart”. Porcupine Tree would sneak through; they sounded more modern and fresh and decidedly non-pop in a period of my life where I foolishly spurned pop. The others would have to wait.

A few years later, having summoned up the gumption to go dig up my parents’ shrink-wrapped copy of Yessongs from the basement and throwing on the longest cut I could find, I would be immersed in prog proper. It was shortly after that first bursting epiphany of how much I could love the genre that memories of all of those interviews I read with the artists I loved came rushing back. There were the obvious vectors of interrogation, of course: King Crimson, Genesis, Jethro Tull (whom I’d loved as a boy due to my father’s CD copy of Past Masters). But quick to hand was Camel. Opeth was, and in many ways still is, so deeply personal it sits in the bleed space between spiritual music and the score of your spirit. That Akerfeldt was so adamant about this band that I had otherwise heard nothing about was of tremendous weight to me.

At the time, ProgArchives, far and away the best compendium of progressive rock in all its manifestations and likely the best there ever will be, had mp3s of various bands available for streaming on its site. This for a period of several years was one of the primary ways I would discover new bands and even entire genre spaces within the broader umbrella of prog. Someone, somewhere, be it on the forums I spent so much time on or in an interview with an artist, would mention some prog group and, a few clicks later, I would discover there was anywhere from one to ten songs available to listen to immediately. Camel’s selections were surprisingly full, covering all of their classic run. I pressed play on the first, which would autoplay all of them, and laid back on the overstuffed loveseat I had pinched from my parent’s living room and moved upstairs to the room that previously had been my brother’s bedroom before he moved out where I had my computer setup. The heat of that room, which often mysteriously resisted the ungainly force of the home’s modern centralized air conditioning, was deeply conducive to sinking deep into the headspace of a record, the scorching broil bubbling my brain into a mystical and receptive state in a period of my life where I didn’t drink and had stopped taking drugs; this mystical heat, combined with my at the time untreated bipolar disorder and undiagnosed place on the autism spectrum, produced a kaleidoscopic sensory wormhole that intensified and force multiplied art into infinity, like placing it under under the omega electron microscope until I swam in the monads of creation.

My brief listening session left me with two general thoughts: I generally liked Camel, albeit likely not as much as my hero Mikael Akerfledt, and I really liked that one about the goose. A couple clicks later and I had a set of CDs headed to my door.

***

Perhaps the greatest charm of The Snow Goose is the fact that it’s the only Camel album that’s fully instrumental. This isn’t meant, despite how it might read, as a slight against Latimer’s vocals, which have the same resonant and ephemeral quality as Steve Hackett’s vocals he would demonstrate on his solo albums. Latimer is never a bad vocalist, at the very worst a serviceable one, and on certain tracks such as “Lady Fantasy” from Mirage or “Unevensong” from Rain Dances even reveals a subtle transcendent power, where the vocals seem to bubble up naturally from the song itself as if hummed by angels or else the music of the spheres rather than something as crass as being consciously sung by a frontman. The vocal pieces of Camel’s oeuvre however always seem on their albums to be the weakest songs, vocal movements the weakest movements of suites. This is due more to the patient impressionistic imagination the group in general and Latimer in specific have as instrumentalists and composers. Their vocal tunes are odd somewhat, almost resolving the band back down to a post-Hendrixian/post-Santana (think the ’60s to early ’70s iterations) type of psychedelic hard rock. These pieces from the group are pleasurable and not without their charms.

But suddenly, the vocals cut out and the band’s abilities unfurl like a mighty banner. Their phrases become longer and longer but never lose a dynamic and rich melodic sensibility. The Snow Goose is beyond a collection of good songs; it feels immediately enchanting in that primal and childlike sense of the world, often feeling closer to that magical sense of otherworldliness you have as a six-year old tucked in some forgotten corner of the house as you bury your nose in some science-fiction or fantasy novel plucked from a likewise forgotten bookshelf. The fact of its basis in a short children’s novel from the ’40s feels self-evident even before you learn it. It’s baked into the sound, into the very existence of the work. Ironically, it turns out that the book that it was based on, clearly trying to live within the same world as A. A. Milne’s masterpiece Winnie the Pooh novels, is substantially more cloying than the album it would later inspire. The wordlessness of the album becomes a saving grace in a second way in this manner, allowed first to shape itself broadly on the emotional arc of the book and then later forced to elaborate more specifically with lyrical solos and lead melody lines on flute, guitar and synthesizer taking the place of vocals. Incidentally, the band did originally intend to record vocals for the record based on the book, but struggles with the estate of its writer meant that they defaulted instead to an instrumental rendition.

There is a naturalness and immediacy to the melodicism of the album. It feels often to me as though they simply took the vocal lines intended for the album and emulated them as closely as possible on instruments, something I know cannot be true based on the real history of the composition of the record. But this sensation ultimately comes from how deeply lyrical and songlike the group’s playing is. We have some ungainly and clumsy words for this type of thing, “playing with feeling” or “playing with soul.” I hesitate to invoke those because they tend to imply the opposite of what they intend, revealing that the person who utters them doesn’t know how to feel the feelings that motivate music outside of a very narrow band of aesthetic sensibility. But that sensibility feels tailor-made for the melodies that fill every corner of this album, almost like an on-the-nose caricature of how these feelings might be painted in music but pulling back at just the last second, such that they feel like comically perfect crystalline distillations of emotion and sensation. A worse hand would have nudged things just one micrometer further, too far, into the realm of self-parody; Camel’s hands, disciplined and steady, keep things precisely on that razor edge, fully indulgent but never teetering over into oblivion.

There is a quintessential ’70s-ness to The Snow Goose as well. This was the era that gave us that magical early run of Sesame Street, a show that in hindsight was home to some truly wild jazz-fusion and prog rock as its soundtrack covertly making the youngins hip to that good shit in an era where it was slowly falling out of vogue. Likewise, between the works of Ralph Bakshi and Scooby-Doo, Hanna-Barbera and fantasy films, there was an aesthetic concentration of these kinds of impressionistic fantasies set against music that fused the smooth, the funky, the proggy, the poppy and the jazzy into one intermingled figure. Gripping The Snow Goose‘s cover, headphones on, ears filled with this music which draws from the same inspiring sources as Genesis albeit with a touch more awareness of funk and Pink Floyd, it is hard not to summon up those same associations. You can practically imagine this as the soundtrack to some animated film, the grain of the recording of the voices imperfectly matching the movement of their mouths, the juxtaposing defined and separated colors of the figures against the painterly and impressionistic backgrounds. I have a firm and perhaps generationally-restricted memory of spending my childhood with those types of cartoons; that The Snow Goose, an album based on a children’s novel, would aesthetically replicate those spaces and thrust me back again into the emotional headspace of those years, only deepens its intended power.

The narrative of the record is a fairly simple fable. The soldier Rhayder abandons the frontline in World War I and finds himself in a town where, along with the young girl Fritha, he discovers a wounded snow goose. The two of them nurse the goose back to health, only for Rhayader to be called inevitably to return to the frontline. There, he is fatally wounded at the battle of Dunkirk, a famously chaotic and apocalyptically violent battle. Afterward, Fritha receives news of his passing and begins to cry, only in her tears to spy the returning snow goose, who lands before her and seems to greet her knowingly before departing again. She reads this as the soldier returning to her to say goodbye, to thank her for the brief period of peace and hope and healing he experienced acting as a sort of father to her, to rejoice in the calm of nursing a wounded animal back to health as opposed to causing only violence and harm and death and war. As I said before, this narrative is obviously one that’s more than a bit on-the-nose; the prose version becomes a saccharine mess and fast, often squandering its brief lucid and beautiful serene passages ruminating on the seeming perennial paradoxical coexistence of healing and war with melodramatic hackneyed tripe.

Stripped of the specificity of prose, Camel are able to tap into their watercolor impressionistic evocations of the emotional structure of the tale instead. There, they are able to sequence the raw emotions of those lucid and powerful ruminations. Characters are allowed leitmotifs not unlike an opera or a traditional piece of programmatic Romantic-era orchestral music, motifs which can be layered and truncated or rearranged to match their longing, their joy, their peace, their sorrow. Latimer as a player and composer lives much closer to David Gilmour’s masterfully, emotionally rich and deeply resonant playing. He is unafraid to lean deep into the emotions he’s trying to summon up and, in the world of pure through-composed instrumental music, this is a gift and not a curse. By your ear alone, you can follow the slow build of joy from the ruins of pain, developing into a gnomelike and very European sense of familial bliss and peace, only to descend back into anxiety and sorrow. The portrait of Fritha’s sorrow at the news of her father figure Rhayader’s passing and its transition into the heartbreaking, heartlifting bittersweetness of his soul’s return on the wings of the snow goose feels like a knife to the heart. What in the book feels oafish and overbearing in Camel’s hands becomes a profoundly affecting portrait of the strange complexities of grief and treasured memory. The war destroys Rhayader, both physically in death and metaphorically in its transformation of him into a killer. But Fritha will always have seen him at peace, producing and salvaging life instead of squandering it, in unity with nature as opposed to set against it with the nerve gas and tanks and machine guns of the mechanized death-industry war.

The group has performed the entire suite as a single unbroken piece substantially more often than they have ever played its movements alone. This is of a profound benefit to the music, especially to its emotional heft. These interweaving thoughts on war, grief, solace, fear, redemption, love, comfort and peace don’t work in isolation from one another because they don’t exist or come in to being in isolation; like the flesh of the world and the heaving of history, they are dialectical, intersectional, permanently entangled in one another and themselves. They achieve power because of how they contrast and reveal elements of themselves in the presence of one another; peace can be so profound you break down only in the presence of the darkness and nihilistic consumption of war while war becomes so painful because of the peace it annihilates. There is a haunting of grief in all love, like bitterness in a desert.

It takes tremendous, impossible discipline and craft to translate these things into words. This is in part because we tend to take words too seriously, fixating more on their objectivity, their specificity and materiality, rather than the impressionistic gesture and unnameably vast emotional and experiential space that lives behind them. Evocation in art is less about saying every detail than it is saying the precise right sequence, ones that function like a seed in soil, such that it naturally blossoms and effloresces in the heart into the precise undefinable shape intended. Prose and poetry struggles with this; there is a gap, a slippage between the word’s precise meaning and the intention, gaps which multiply and concatenate until it becomes a loose haze you can only hope captures well the intended function. Music tends to be much better at this. There’s something about sound and our response to sound that sits far more naturally close to the heart. Perhaps this is why cadence and sonics are so important in poetry, letting things be led more by how words feel as sequences of sound than as pure constructivist meaning.

Regardless, Camel seem naturally keen to this kind of power. Their approach to prog veers far from the image of technical geniuses and advanced mathematics. There is a considered and simple sense of musicality to their phrases, ones that cut to the quick of the complex emotional valences of the scenes and do so uncomplicatedly, eschewing the potential distractions of virtuosic flair or starry-eyed bong-scented poetry. That they would later play this song suite live with the London Symphony Orchestra feels only fitting for the piece, drawing as it does more from the prog rock tradition of orchestral rock hybridization. But while for some prog bands, the composers in question are more along the lines of Bartok and Stravinsky, Beethoven and Paganini, Camel lives in the contented and luxuriant spans of Debussy, Brahms and Chopin. Those composers certainly had pieces that would demand great sharpened chops from their players, but they are perhaps best known for their imagistic power, how they wielded their melodic and harmonic intentions toward evocative and rich sound-images. The Snow Goose lives comfortably with those greats, feels at home among peers when placed next to those minuets and nocturnes and lullabies, some of the greatest ever written. That Camel’s heights were humbler than some of their more commercially dominant peers in the era only adds to this sense. With Camel and The Snow Goose, there was no grandiose or pretentious claim to long-lasting greatness. There was, instead, the music itself: beautiful, translucent, alight like an angel suspended in a sunbeam.

***

The album over the years became a natural if unnoticed fixation of mine. I was a drummer as a child, rebelling against a family of guitarists and that nagging sense as a younger sibling of being indelibly defined by the actions and tastes of my family over myself. This was a noble intention, certainly, and I still carry a drummer’s fixation on rhythm and groove. But inevitably, the natural impulse won out and I found myself picking up the guitar. On paper, this was so that I could convey musical ideas more directly with potential bandmates after my brother, whom I seemed to share a musical telepathic bond, went off to automotive school in another state. This was perhaps half-true. The bigger reason was simple: much like there is a raw emotiveness to singing, even if its untrained and yowling, there is a rock-instilled belief of the inherent majesty of an electric guitar, an unwavering and unspoken faith that Hendrix could do more with his hands than any vocalist could ever do on a microphone. I was an ardent lover of rock ‘n’ roll and heavy metal and prog. At some point, you pick up the guitar. There is no way to stop this.

The Snow Goose seemed to come natural to my fingers. I would put the album on in the early and haphazard years of learning how to play, when I didn’t know a lick of theory and could barely handle playing more than one string, and even still I would find the melodies coming quick to me. This was perhaps in part to having an okay ear, something anyone who plays music even recreationally for long enough will develop. But a larger part of this was because of how instantly memorable The Snow Goose‘s melodies are. I felt like I’d known them for years within an instant and, as such, found them as easy on the fretboard as you might find the notes for “Hot Cross Buns” or “Mary Had A Little Lamb.” I would struggle for years as a drummer forcing himself in secret to learn the guitar to grasp even fundamentals like the fundamental open chords and how to navigate single-note melodies that move across the strings. But even in that clumsy and primitive place, the notes would come, allowing me to sink into that meditative and synchronous place you can only go to by playing along with a record, enjoining with what I heard, sitting fully inside of it. This was a comfort, an encouragement.

Years later, in the wake of my father’s sudden passing one year to the day of my suicide attempt and the way that seemed to finally collapse the negativist fatal psychic singularity threatened in my brain, I would cast out desperately in search of some life raft, some island of peace within the whirlwind. I would write like a madman between my suicide attempt and my father’s passing, a habit I would double down on in the weeks and months following his passing, words unspooling from me in a dense and aimless snarl aided by the mind-destroying combination of whiskey, espresso, maximum strength anti-depressants and klonopin that I was emulcifying my brain with to keep the naturally occurring self-annihilating thoughts at bay. As I have said before, however, there are certain spaces where words cannot go. There are certain emotions that, rendered into the specificity of prose, suddenly become infinitely thin, brittle. They lose the world-filling capacity of emotion, those swirling and roiling clouds of hope and darkness, terror and love that crash and cascade into each other like the thunderous waves of the sea suddenly dimming into the tink and thud of a child slapping toy cars into one another. That which once tormented your heart and offered you tear-filled peace, a peace now streaked with the gentle graying of pain, becomes a hackneyed and melodramatic mess. Those moments of grief and confusion are not all pain and darkness. There is joy and love there, a fervent and inconsistent desire toward life and being, a silent war between annihilation and continued existence. It just isn’t something that consistently survives the translation to the imperfection of language.

In those moments, I would pick up my guitar. My father was a guitarist once. One of my fond memories before he passed was sitting on the steps of the house, stereo blaring so loud it shook the walls, just like in childhood, playing along to Lynyrd Skynyrd and Pink Floyd songs while my dad sat and smiled back. We’d had our fights and my home was no stranger to strife, as many homes happen to be behind the closed door, but we did love each other. (The pain endured in those years would not have hurt so much if we didn’t.) When even I could sense my substance- and madness-addled mind was producing nauseating nonsense on the page, I could grab my guitar, turn on my amp and play. There is a power to the heart in that place; you can hear a chord or a single note or even just a tone of the instrument and know immediately if it matches the contours of your heaving heart. The emotions are right up in your throat, so hot in your veins it feels like it’s burning your skin. You know instantaneously the right note from the wrong one. I was no virtuoso, nor am I now, but I could put on a record that was dear to me or dear to my father and manage to eke out those feelings when words just wouldn’t do. It was an act of silent faith. I’m not religious anymore, but I once was, and the loss of a father is one of the things that will rekindle those feelings even if only for a painfully brief moment. I would play the guitar, eyes closed, focused on the note, and I would be with my dad. I would tell him I loved him. I would promise him I would be okay.

One day, on a lark, I put on The Snow Goose. This was for no deeper reason than one of those urges came over me again, the desire to speak and commune with a guitar rather than words on the page, and I remembered being okay at plucking out the melodies on that record. That brief span, less than an hour from pressing play to the final notes of the record, became a window of peace and beauty, a small and tranquil coast girded by a breakwater in the middle of a turbulent sea. I felt briefly free of grief, ensconced in the picture-book watercolors of their evocative playing, tamed by a vision of illustrations of snow geese and World War I veterans and a girl holding a wounded animal. This association with the album was not necessarily a new one for me but, experienced in that period of profound pain, it intensified until it became for me the defining characteristic. The Snow Goose represented to me peace, the abiding power of healing, and the notion that someday things lost might one day return, even if in a disguised manner.

At some point during the record, the associations between its story and my family’s pressed deep into me, as overbearing as a badly written novel. My father was a war veteran too, having signed up for or been drafted (no one really knew which) for the Vietnam war when he was just 18, hurled into a Hell of imperialist and criminal making. He did not flee the war except inasmuch as anyone fled it, taking a half-dozen tabs of acid on the plane ride back to Hawaii and then home to South Carolina to try to wipe away the years of terror he’d experienced. It didn’t work, nor did his home life, living with a World War II vet and the toxically masculine notion that you never discuss the hurt and terror you experienced over there, never to women (who couldn’t understand) and never to men (who didn’t want to talk about what they’d seen either). Life after the war in its intervening decades was his way of tending the snow goose: going to college, entering the world of advertising, meeting a number of women he’d marry and divorce before meeting my mom, having my brother and me, raising a family. The specter of the war was always there, though, not only in his PTSD but in his rapacious drinking, drinking which eventually if indirectly led to his death. That, in a manner of speaking, was his return to the front, his Dunkirk, his fatal bomb or drifting cloud of mustard gas. And then there I was, listening to The Snow Goose, guitar in hand like I had taught myself after refusing to let him or my brother teach me, waiting for my goose to return from the sky so I could properly say goodbye.

There was a bitterness to this association, of course, and I’m not going to pretend I didn’t cry with the guitar in my hands. But the lasting impression of it, and, from it, of The Snow Goose itself, was that of peace. There is a power to things that lift those thorns out of us, give them names and defined shapes. There was something transcendentally beautiful to me in the simple image of that which remained after the war: Fritha, the goose, the time spent nurturing instead of wounding. The album closes on a mysterious and somewhat melancholy note, perhaps indicating a cynicism that this cycle would ever be meaningfully broken. But the cycle includes not only war and death and loss and pain but also peace and love and healing and beauty. That notion struck me before as almost unbearably corny, if I’m honest, but the heightened sensitivity of profound grief made that thought not only more palatable, it revealed a subtle kind of wisdom behind it. We sometimes conceptualize progressive rock or hear others talk about it as a series of technical showcases, literary references and aggressive almost anti-listener juxtapositions of sound. We don’t often hear it discussed as something that helps process and understand pain, to find love and peace within suffering and loss. But, in truth, as perhaps unbearably corny as it is to say, that’s what The Snow Goose is for me. I can put it on now, almost a decade after losing my father, in a time when the pain of that loss has dulled to the same gentle persistent throb that anyone who’s lost someone close will know, and I can see the table clear as day, feel the sunburst Epiphone Les Paul in my lap, feel peace.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.

That was so great, so interesting, so well written. I love the snow goose. Also came to opeth first and then heard that album and it was just amazing and for some reason it clicked with me during a period of grief too. The great marsh, when it starts, just overwhelmed me. All the instruments came in and I could feel myself floating away. Album is still magical and I will listen again today. My dad had this record before we both got into opeth and we both still love it. Anyway, thanks for writing!