Girls Against Boys closed a taut, tense trilogy with ‘House of GVSB’

In the wake of Nirvana’s 1991 success with Nevermind, independent bands flourished as major labels searched feverishly for the next underground breakout, and hovering just under the top of this list for roughly half the decade sat New York City’s Girls Against Boys. The group’s first seedlings were planted in 1987 as the recording project of Brendan Canty in the interim between his tenure in Rites of Spring and then Fugazi, and Edsel’s Eli Janney, bringing in their friend Scott McCloud from Soulside for vocal duties.

“Eli called me one day and said, ‘Hey, Brendan and I are out at Inner Ear studio and we’ve made a song would you be able to come sing on it?’” McCloud says. “So I went over, and this first song would become ‘Skind’. I think at that time my vocals were still very heavily influenced by Guy from Rites of Spring/Fugazi. I had not really found my own thing. Rites of Spring had made such a massive impact on me, it wasn’t until I started listening to other stuff—The Fall, even Velvet Underground—that I started to get to the place that happens on Venus Lux, which is far from good singing, but more of myself personally if that makes sense. The main thing for me was I didn’t want to be copy of someone I admired. I wanted to find myself somehow, in the music.”

He talks of living in Boulder, Colorado before Soulside and discovering Big Black, Einsturzende Neubauten, Skinny Puppy, Sonic Youth, and Killing Joke, influences which, piled on with his background of D.C. hardcore, would stick with him throughout GVSB’s tenure, warping his approach to vocals even more as he discovered The Fall and Velvet Underground.

Janney adds, “we were definitely inspired by the industrial/electronic scene in Chicago at the time, mostly centered around the WaxTrax label. I was working in Inner Ear studio at the time and had access to free studio time so we would just go in late at night and mess around with sounds and songs outside of what we were doing in our other bands. We definitely were trying to make different music. It changed when the band coalesced into the final form, because obviously we had to then perform live every night.”

Like a lot of bands, I think we weren’t sure how to process what was happening with our group at that time. It created anxiety, which we defused with humor and irony

The four members who would eventually comprise Girls Against Boys—singer/guitarist McCloud, bassist Johnny Temple, keyboardist/bassist Janney, and drummer Alexis Fleisig—enjoyed a friendship that went back to middle school in Washington, D.C. After high school, McCloud, Temple and Fleisig eventually found themselves in Soulside, and Janney began playing in Edsel and as well as cutting his teeth in the late ’80s as a recording engineer, leading to a career behind the sound board for a number of bands to this day. (He’s the keyboard player and Associate Music Director of the 8G band on Late Night with Seth Meyers). After the dissolution of Soulside and with Canty’s heavy involvement in Fugazi, the four found themselves living together in the same city for the first time since school. Janney recruited the other three, and they began writing together under the Girls Against Boys moniker.

“Everyone had relocated to NYC and we started to rehearse regularly and mostly recorded those rehearsals on a boombox with cassette tapes, and I’d often take these tapes home and listen endlessly and isolate the areas that seemed cool,” says McCloud.

This batch of songs ended up becoming their first LP, Tropic of Scorpio, which would begin to solidify much of what made GVSB what is was: sardonic humor, D.C.-style post-hardcore butted up against dark lounge, things that were already apparent in the six tracks that make up the 90s vs. 80s EP. With a full album in the can, the band was ready to begin playing out, taking their songwriting out of the studio and into the live space, where they found their niche. Their mix of seedy warped-disco rock, post-punk and distinctly rhythmic noise-rock carved a singular place in the world of underground music. As their sound started to expand, some felt that the band’s prospects could as well. McCloud says, “a friend in New York, Grace Jeffers sort of commanded me to call Corey Rusk at Touch and Go, and I did, and he visited us in our Brooklyn loft in South Williamsburg and signed us after hearing a boombox recording of some practices.”

Thus Girls Against Boys had a solid home in the reputable Chicago label, bridging their Dischord post-hardcore roots with the noise rock more prevalent in the experimental world of Touch and Go and the likes of Jesus Lizard, leading to their first album for the label, Venus Luxure No. 1 Baby.

“In my view Venus Lux is the 4 of us recommitting to being in an actual band, and starting over (from Soulside) in New York,” McCloud says. “We’d done some touring prior and had come to realize some negatives of a ‘studio project’ approach, namely that it sometimes wasn’t as cohesive as the ritual performance of practicing. For us in a way going back to that approach greatly improved the quality and depth of the material, and the songs became more nuanced on Venus Luxure. I think this is from taking that step to make a real band out it.”

Janney adds, “I feel like the Venus Lux sound really came out of the touring that we did previous to recording the album, mostly on the reputation of Soul Side and the Tropic of Scorpio album. It was some pretty rough touring, with a lot of shows were people didn’t want to see us, so we really honed our skills to get and keep their attention. We definitely wanted to be heavy, but with some rhythmic swagger. Once Venus Lux came out it all kind of changed, because of the positive reaction to that record. We wanted to build and grow, but keep that core sound and feeling. You can’t really ignore what you’ve done before, at least so early in our career.”

McCloud expands on this idea: “Overall we were also in a very confident period. Being accepted on Touch and Go gave us the feeling of having a musical family, so to speak, a lot like Dischord had been for Soulside. You just felt like being yourself was OK. Sure, there were doubts about ideas, or songs, or finishing lyrics, but overall we didn’t have time to overthink the process. With Venus Luxure, Girls Against Boys suddenly started to ‘happen’ a little bit. I think mainly because the sound of the band was somewhat novel—we’d started using double basses in order to not have Eli on keyboards for every song, keyboards were still not quite ‘cool’ back then, though I always thought it was an interesting and important thing to incorporate into what we were doing. But again, since Johnny, Alexis and I had been in a band we already had a very natural way of playing together and vibing off one another.

“Eli on bass also brought a lot,” he continues. “He was not used to playing bass, a limitation that proved to be a strength as some of his parts had a cool minimalism that was great, and he was very adaptable and able to play parts that were repetitive. I was also singing in a non-melodic kind of way, which at the time got comparisons to the Fall. Basically I did not know how to sing in a ‘proper’ way, but I also wasn’t interested in that. I think punk, or post-punk, or whatever you want to call it, thrives on some amateurism. You just do it, and use your limitations as a strength. Or try to. We also started using a lot of distortion pedals. On all the instruments, as well as the voice sometimes. We were going for a bit of a more aggressive sound and a lot of that probably comes from the move to New York, and the local influence of what was happening then in the clubs.”

With some real momentum, sonically and otherwise, Girls Against Boys began putting everything they had into it. “After Venus Luxure came out on T&G we basically went on the road for years,” McCloud says. “Playing on our own, but very importantly supporting bands like Jesus Lizard. We gave up our South Williamsburg loft, in New York, and committed to being on the road, and being a live band. There was never any time to waste. We toured, and then when back in New York, practiced and wrote, and still recording our ideas on a boombox. I would take the cassette tapes and listen to them endlessly on a Walkman, often out at night in NYC. Watching people. Writing notes in the corner. Then to the studio. One record after the next.”

The relocation to New York City would prove inspirational in a number of ways, says Janney. “Manhattan was way more sleazy and lawless, which gave everyone more freedom to do what they wanted, good or bad. It helped us be inspired by the city itself, keeping our music gritty and hard edged.”

The band continued at a breakneck pace, writing and recording their second LP for Touch and Go, Cruise Yourself, the next year. “We made these records pretty fast, and I always liked that because when I say ‘practicing’ I don’t mean we overworked the ideas,” McCloud says. “I think it’s important to leave room for surprises in the recording process. This was particularly true regarding the vocals and lyrics. Even though I obsessed on the practice tapes I could never seem to nail down exactly what I was going to say, or sing, on a particular song until the moment of dong it. I’ve come to realize, later in life, that this was not because I could not have written it down, all in order, beforehand, but rather because I actually liked the feeling of leaving some room for surprise. I wasn’t ever sure if I’d have the courage to sing some lines until actually doing it. ‘Kill the Sexplayer’ comes to mind. If I would have had months to second-guess myself and get filled with self-doubt I might have changed it.”

It’s a good thing he didn’t; that track landed in the film and on the soundtrack for Kevin Smith’s indie breakout film Clerks, and its predecessor on the album, “Cruise Your New Baby Fly Self,” in Smith’s following film, Mallrats, and the band would find itself on plenty of soundtracks around this time, including Richard Linklater’s SubUrbia, Ben Stiller’s Permanent Midnight, and an appearance in 200 Cigarettes. But however much their attention grew in the music and film world, McCloud made sure to not let outside pressure impede on what the band was creating.

“There is something about allowing oneself to freely do something without the stress of too much worry that can make something happen,” McCloud says. “Touch and Go allowed us this privilege. The only time Corey Rusk ever even commented in the process of what songs were going to be on an album was for House of GVSB. He called me and asked if I wouldn’t change my mind about having the song ‘Wilmington’ be an album tracks instead of a b-side (I originally wanted the song ‘If Glamour is Dead’ to be on the album instead). It was cool, to me, that he felt so strongly about it so we switched them up and made ‘Glamour’ the single b-side to Super-fire’ instead.”

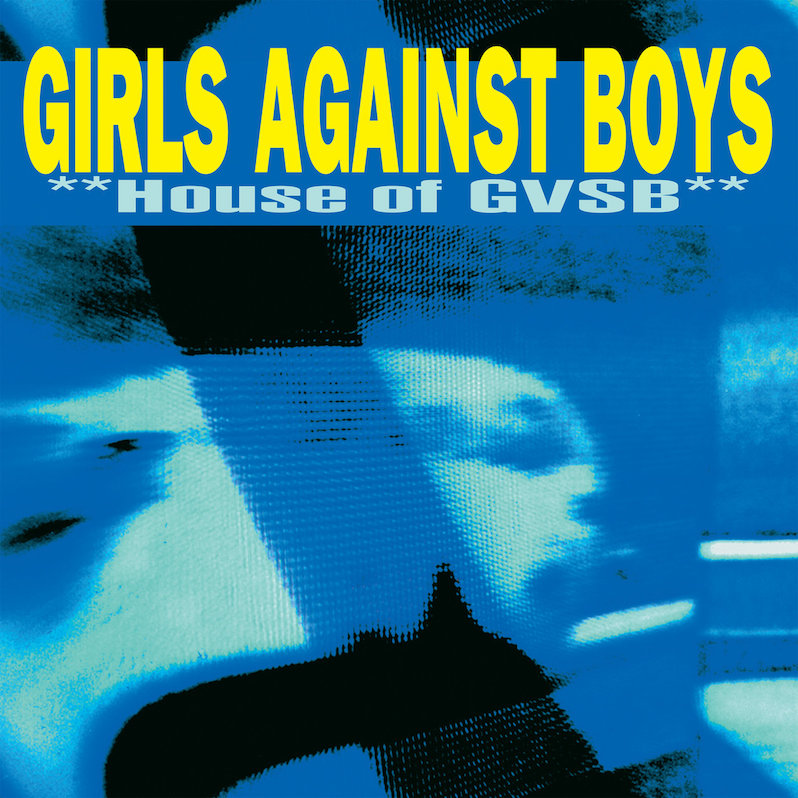

That album, House of GVSB, was the capper of the trilogy following Venus and Cruise. It revealed the band in top form, and would prove a gateway to being signed by major label Geffen Records. House of GVSB is McCloud’s personal favorite, as well as one he says is “overall the most consistent in sound and approach.” It also marks the third and final album working with producer Ted Niceley, who was intent on capturing what the band was striving for without interfering in the process, and proved a valuable asset in the distinct sound of those records and in giving the band the freedom to experiment.

“Similarly to Touch and Go, Ted never interfered in any way that wasn’t positive,” McCloud says. “All he would normally focus on was the groove of the drum patterns, and digging into what the basses and guitars were doing. But not intrusively. Not to clean everything up, but sometimes to just see what might be going on that was a conflict we were not intending. When you record practices on a boombox there is a lot of compression in the sound in playback so there can sometimes be a moment of revelation in the studio where you finally actually ‘hear’ what is going on. It’s like ‘is that what you’re playing?’ And by that I don’t mean too much more than bringing things to our attention, and then we’d all work to either resolve it, or keep things as they were.

“Personally, Ted was amazing working with me,” he adds. “I think he instinctively knew the kind of person I was. In the vocal process I would sometimes agonize a bit about certain minor things, and he was great at saying ‘take a break, come back in a couple hours’. He never, ever told me to change the way I was singing in a general sense. He was passionate about the recordings and about our band. Of course, there were arguments from time to time. I remember one wherein I wanted to sing ‘The Kinda Mzk You Like’ in a more laid back way than he thought it should it be. The discussion got so heated he threw a standing ashtray across the room and stormed out. In the end, we compromised. This wasn’t a negative thing; in fact, I was stunned by how passionate he was about things, and this made me want to work even harder. And I think the results speak for themselves. Over the course of these three albums Girls Against Boys forged our sound, as a band, and he was at the helm. But I think most importantly he knew that to fuck with things too much could poison the whole thing. He never came close to doing that. We were not about writing pop songs. This was noise rock, really. And rather dark and that’s what we were into. The job of a producer is to see, to hear and to understand the band, the dynamics within the band, even the personalities, and get the best performance you can out of a group of people and have them feel its a positive experience. And Ted was amazing at this.”

There’s a quote from the band sometime after the release of House about how their music is “about wanting something you don’t have, having something you don’t want, speedboats, and shotguns,” as tongue-in-cheek and disparate as the band’s music itself.

“I think it was Alexis who said this…around the time all the major labels were courting the band, in that ‘90s period when labels were doing that, and one of the ways we dealt with that as a group was to view the whole thing with some level of sarcasm and humor,” McCloud says. “The ‘indie vs major label’ conversation was a hot topic, and like a lot of bands, I think we weren’t sure how to process what was happening with our group at that time. It created anxiety, which we defused with humor and irony. But of course the songs aren’t about speedboats and shotguns. ‘Not having what you want, and not wanting what you have’ is more to the point. Already in the ’90s, in a world of rampant wealth and celebrity it seemed part of life was imagining what you didn’t have. And contemplating this juxtaposition. Even if it’s grotesque, or not based in reality.”

The mid-90s era of GVSB’s strongest creative output existed alongside like-minded acts of the era like Unwound, Blonde Redhead, Shudder to Think, and Brainiac, almost a completely different time in which bands could think both big and different, in which it was feasible to not fall into status quo expectations of what music should be, in which the challenging nature of what was being created was exactly what was being celebrated.

Those “bands…all have such a distinct sound…and I think this comes, or came, from the process of creating it,” McCloud says. “And I mean the long view, the ritual of practices, the countless hours of that process, wherein one’s perspective changes and what may have once seemed a bit strange starts to feel completely normal. I mean, artistically speaking, what a band does in practice is normalize the weirdness of what they are doing into a common language, a sort of common pool of assumptions about what is taking place. This takes time to develop. Things evolve, very slowly. When you are in a band, what you are doing is kind of creating your own reality. I do think that the way we now consume music has changed, very much, the way we create it. I think, at the time, we thought of our music being for the future, but of course the future has a way of being surprising.”

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.