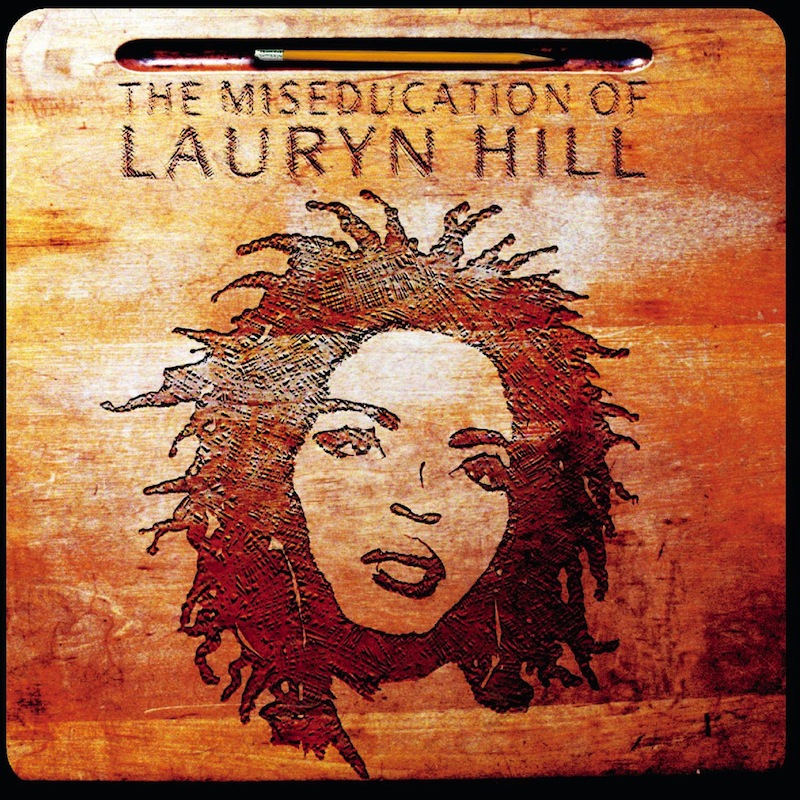

The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill shaped an era’s perception of what a performer could be

“I wrote these words for everyone who struggles in their youth,” belts Lauryn Hill on her triumphant hit “Everything is Everything,” off The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, now celebrating its 20th anniversary this summer. And indeed, the album, even still today an incredible commercial achievement for a debut album, was a triumph. Her rise as a lyric-minded rhymer late to rap’s Golden Era and as a multi-disciplinary entertainer when so few did it well was improbable, but could not be denied. Where Queen Latifah and MC Lyte blazed the trail, Lauryn Hill built the highway.

Hill had a charisma that predated Miseducation. As a member of the Fugees, she generated considerable buzz on the trio’s 1994 debut Blunted on Reality. Her mic skills and wordplay didn’t square up at the time with her youth, Hill being only 19 when the album was released. Her willingness to own being a cerebral, suburban youth from New Jersey, while other rappers repped criminal lifestyles, was bold, courageous and probably seemed like career suicide back then. Regardless, The Fugees’ natural chemistry and potential did not stop major-label support for Blunted, which never really sold beyond the number-49 charting “Nappy Heads” and the slow burning “Vocab.” The group’s 1996 breakout The Score would set the pop music world on fire, and L-Boogie was regarded as the Refugee Camp’s unquestioned star. Young, charming and gifted, Hill was instantly magnetic on camera. Her ability to effortlessly sing and rap at such a high level on hit covers like “Killing Me Softly” and “No Woman No Cry” as well as the Fugees’ original tracks “Ready or Not” and “Fu-Gee-La,” made talk of a solo album inevitable. Yet Hill also displayed public vulnerability as a performer and a reluctant acceptance of fame. Few felt as raw or entrancing, and Miseducation would open up Lauryn Hill in a way fans had never heard.

Recording began in 1997 and coincided with Hill’s relationship with Rohan Marley as well as subsequent pregnancy, an event that would change the course of her music and career. Unsurprisingly, Hill has often said the album was never intended to be commercial and many choices were made to keep it from being mainstream. Miseducation became thus the unlikeliest of hits. Almost all its songs were nearly five minutes or more, which is still poison to radio. It featured songs attacking former Fugees collaborators Pras and Wyclef Jean (“Lost Ones”), eccentric hybrids of reggae and soul (“Final Hour”) and themes traversing Afrocentrity, obsession, fame and love. Nevertheless the beguiling songwriting of Hill and her collaborators, however, would prove too beautiful to be ignored. The album entered Billboard‘s Top 200 at number 1, selling nearly half a million copies in its first week and more than 8 million overall.

For America, Lauryn Hill was that performer who shaped an era’s perception of what artists could be. Her story—raised middle class in a religious household, performing as a child and demonstrating precocious talent—felt instantly recognizable. Stylish, photogenic and warm, Lauryn Hill seemed like somebody you went to school with or who lived in your neighborhood. She was ridiculously famous, but came across as someone who didn’t really want to be, and may have been content as a musician just making a respectable living. And, although many songs explore it, Miseducation’s title track lays bare her insecurities and struggles, which fostered a deeper bond with fans. All those things seem commonplace 20 years removed, but navigating that space was more challenging then, particularly as a Black woman.

Much has been read into and said about Lauryn Hill’s songwriting, and what she talked about on her greatest album. Something not up for debate, though, is that, from its best-known songs to its deeper cuts, Miseducation‘s great subtext was the political character of Hill’s music. While she was undoubtedly conversant on revolutionary politics—name-checking Betty Shabbazz in “Everything” and Carter Woodson’s Black cultural scholarship—so much of Miseducation spoke to her deeply held moralism. In general, Hill was able to address politics in a way that was subtle—mentions of injustice are fleeting, but there were analogies aplenty—that made them accessible to more people. Strains of Hill’s old style can be heard now in songs like Beyonce’s “Freedom.” Hill would break that formula on 2002’s MTV Unplugged 2.0, getting explicitly radical in tracks like “Freedom Time” and “Mystery of Iniquity,” which the audience didn’t follow for many reasons, including the unfocused nature of it all. Hill’s fearlessness in judgment on Miseducation, however, made it unusual for pop in the cultural period, where the neoliberal acceptance of everyone’s whim we see today was just getting inducted into corporate policy.

L’s hit “Doo Wop (That Thing)” was essentially an anthem for a return to more traditional values, while chastising women for casual sex and men for “acting like boys.” Elsewhere, the popular culture probably wasn’t prepared for a performer of Hill’s stature to offer the unapologetically anti-abortion “To Zion.” During this period, abortion rights as a movement was en vogue, with many celebrities active around the cause. Interpolating the popular anti-abortion suggestion to choose life, Hill’s narrative was cut from her own reality, before the birth of her first child, after whom the song is named. “I knew his life deserved a chance, but everyone told me to be smart/’Look at your career,’ they said/’Lauryn, baby, use your head’/But instead I chose to use my heart.” Hill mused, “And I thank you for choosing me.”

Twinned with this perspective was a strongly spiritual worldview Hill weaved into her album. Retrospectives of Miseducation have often remarked on the at-times heated debates over content, since so many themes were diametrically opposed to what you’d hear in pop singles. “Forgive Them Father” juxtaposed prayer against the disingenuous music industry. “All I wanted was to sell, like, 500/And be a ghetto superstar since my first album Blunted,” Hill rapped on “Superstar,” a rebuke of fame-mongers and, it is often said, of former Fugees bandmate and ex-lover Jean, with whom she had an acrimonious split that would ultimately end the Fugees. The heartbreaking “Ex Factor,” one of the record’s biggest hits, was also reportedly about Jean.

Beyond the scandalous tracks and excoriating ones, the touching ways of telling everyday experiences may be Miseducation‘s greatest contribution. “Every Ghetto, Every City” shared stories of her middle-class upbringing and the influence of culture on the young (“‘Member Frelng-Huysen used to have the bomb leather, back when Doug Fresh and Slick Rick were together/Looking at the crew, we thought we’d all live forever“). “And if you ever been in love, then you’d understand/That what you want might make you cry, what you need might pass you by,” Hill sang on “When It Hurts So Bad,” one of her passel of love songs focusing on loss. Some critics looked askance at Hill’s approach to ballads, with the Los Angeles Times infamously remarking her voice wasn’t strong enough to carry the material. The public, clearly, thought otherwise. “Ex Factor” would be among her calling cards, but Hill’s introspection in neo-soul classics “I Used to Love Him” and “Nothing Even Matters” were brave choices for an artist steeped in hip-hop.

As Hill’s magnum opus, Miseducation broke barriers and changed the game for not just female artists, but for hip-hop. It is doubtful Drake, Nicki Minaj or anyone else could have as easily been accepted as a rapper and a singer simultaneously without Lauryn Hill. Rare is the MC who can navigate an intersection of culture and politics quite like Hill did. And her peerless ability to craft songs that were meaningful in varied ways to lots of adoring people in mainstream music created a blueprint that Beyonce and a few others inarguably learned a great deal from. Uneven as her career has been since, and as erratic as her performances and politics have come off in the decades post-Miseducation, not a soul can touch what Lauryn Hill has meant for hip-hop, or for pop music.

***