Celebrate the Catalog: Miles Davis

In our first three editions of Treble’s Celebrate the Catalog, we examined the careers of some of the most notable artists to arise from the indie and alternative rock movements of the ’80s and ’90s. Yet, as ambitious as it might have been to tackle all of Sonic Youth’s studio albums, the time seemed right to start an even more audacious discography project: The selected Miles Davis albums.

Twenty years ago, the world lost one of its most incredible and gifted musicians: jazz trumpeter, composer and bandleader Miles Davis. Few other artists made as massive an impact on jazz and popular music as Davis did, his nearly five decades of performing adding up to a body of work that runs the gamut from celebrated to controversial. From the late ’40s up through the ’70s, he was at the forefront of every major movement in jazz, from cool jazz to hard bop, modal jazz to fusion. And within these movements, he took inspiration from a wide range of styles, be it the traditional Spanish elements of Sketches of Spain to the raucous rock’ n’ roll sounds of A Tribute to Jack Johnson and the nasty funk of On the Corner.

To listen to Miles Davis is to hear true exploration in music. At times his albums sounded more composed and melodic, while at others, they were alien and disorienting. Davis was the type of artist for whom experimentation meant freedom and vision. By never allowing any one style to dominate, he left little opportunity for any of his music to grow stale. And by having attempted so many different sounds and techniques, he’s been likened to Pablo Picasso. His influence, meanwhile, is immeasurable, having made an impact not only on jazz, but on rock, electronic and hip-hop. The fact that he wasn’t afraid to make music that some people may not like, at least not immediately, certainly speaks to his boldness as a composer, musician and bandleader. And while Davis had his share of dark periods, from drug abuse to depression, the body of music he leaves behind is immense, and a big chunk of it absolutely essential.

To take on Davis’ entire studio discography would be unfathomably forbidding; with 67 studio albums, just to listen to all of them could take a month. So, in a slight twist to the Celebrate the Catalog modus operandi, I’ve chosen to select 20 of Davis’ albums, in honor of the 20 years since his passing, with recordings culled from all of his notable eras: the Prestige years, his early Columbia recordings, collaborations with Gil Evans, his mid-late ’60s quintet recordings, the “electric” years and his somewhat less well-received ’80s recordings. This selected Miles Davis discography is a musical journey unlike any other. Here’s our take on 20 Miles Davis albums ranked, rated, evaluated and given a closer listen.

Note: When you buy something through our affiliate links, Treble receives a commission. All albums we cover are chosen by our editors and contributors

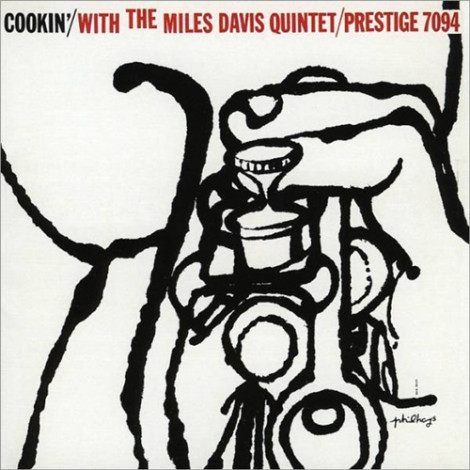

Cookin’ With the Miles Davis Quintet

(1957, Prestige)

With nearly 70 albums in Miles Davis’ repertoire, a good number of those recorded and released in the ’50s, it’s hard to know exactly where to begin. He released plenty of short LPs early on that might prove interesting artifacts in terms of his development as an artist, but Davis’ first truly interesting series of albums is a quartet recorded with his first quintet, culled from two recording sessions in 1956. Each of these albums carries a similar name—Cookin’, Workin’, Relaxin’ and Steamin’—yet the first in the series, Cookin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet is a clear frontrunner of this series. Comprising four moderately lengthy pieces, the album is a strong document of the quintet’s skills. As Davis said about the album’s title, the band merely went into the studio and cooked. Compared to much of Davis’ discography, it’s a very straightforward record, and one with no weak links, though the group’s rendition of “My Funny Valentine” is certainly the album’s shining star. And where Davis practiced more restraint in later years, his splendid trumpet solos are a main focal point of the album. Davis would later soar above and beyond this album, but it’s arguably his first great album.

Rating: 8.9 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Amazon (vinyl)

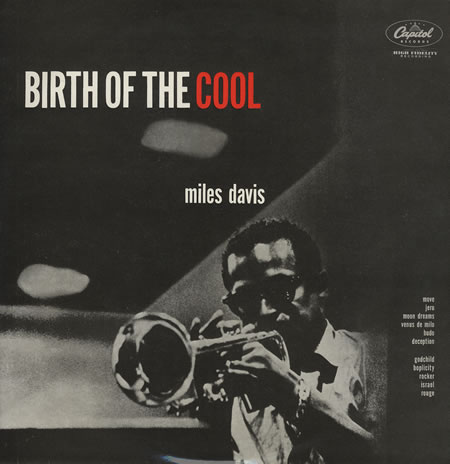

Birth of the Cool

(1957, Capitol)

Birth of the Cool, in addition to being Lisa Simpson’s favorite album, is notable for being, essentially, the birth of ‘cool jazz’. A compilation of tracks from different sessions recorded in the late ’40s and early ’50s, Birth of the Cool is a very different sound from Davis than the hard bop style he’d perfect on his early Columbia albums, or for that matter, his more experimental fusion records of the ’60s and ’70s. Working with arranger Gil Evans, who’d later prove to be a highly valuable partner on groundbreaking works of later years, Davis heads up a nonet that balances big band and swing elements with more laid back bop sounds to create something undeniably cool. It’s stylish, and succinct, with most tracks spanning no longer than three minutes, and pretty lively at that. With the sole exception of the corny vocal piece “Darn That Dream,” there’s not a bum track in the bunch, but at the same time, there aren’t many tracks that really stun in the same way something like “So What” or “Shhh/Peaceful” do. That said, one can hardly love jazz without liking Birth of the Cool, because it’s just so damn… cool.

Rating: 8.7 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Rough Trade

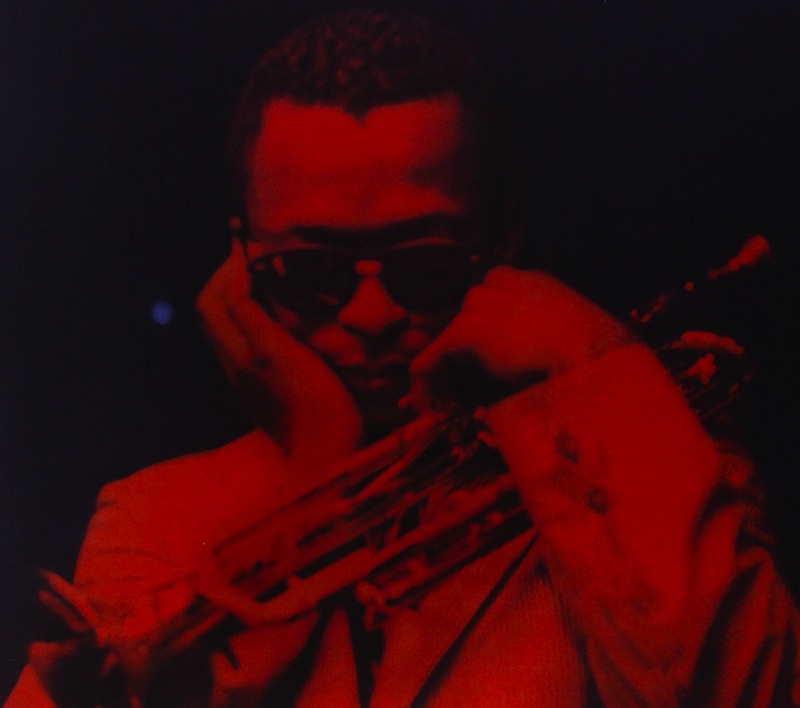

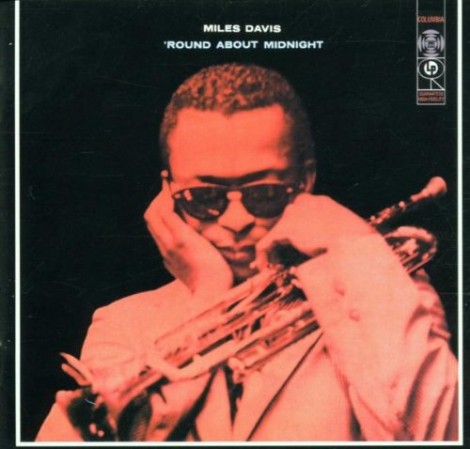

Round About Midnight

(1957, Columbia)

Miles Davis’ first album for Columbia is also his first real stunner. Even more so than on Relaxin’, Cookin’, Workin’ and Steamin’, the quintet sounds incredibly dynamic, nimbly transitioning between breathtaking ballads and vivacious hard-bop pieces. The serpentine harmonization on “Ah-Leu-Cha” is as dizzying as it is mesmerizing, and the quintet’s take on Thelonious Monk’s “Bye Bye Blackbird” is truly gorgeous. But the star of the show is the other Monk-penned track on the album, nigh-title track “Round Midnight.” A moody ballad with a just-so-slightly dark atmosphere, the song is one of Davis’ most memorable performances. In fact, it’s Davis’ weeping trumpet melody that makes this song such a jaw-dropping essential, as his slow, sensual performance pulls the listener into a cool, noir setting. It’s a sound that absolutely never wears out its welcome. And the iconic album cover matches the sound of the music perfectly. Miles leans on his arm, bathed in red light, looking distant but powerful. It’s the first recording of Davis’ that feels like a truly complete album, and a great leap forward in terms of his artistic development. Just remember, the album’s title is almost a set of instructions, because it sounds best around the time the clock strikes 12.

Rating: 9.1 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Turntable Lab (vinyl)

Relaxin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet

(1958, Prestige)

The second in a series of similarly titled albums recorded with the Miles Davis Quintet, Relaxin’ puts a pretty heavy emphasis on the whole concept of “relaxin’.” A drawing of a woman composed entirely of triangles reclines on the album’s cover and, to capture the loose, relaxed feel of the sessions, the album is one of the rare Davis recordings to feature actual in-studio banter. So yes, indeed, this is a very laid-back recording, especially when held up against the other albums in the [Verb]in’ series. But it’s also highly enjoyable. The talent of Davis’ quintet, which also includes John Coltrane, Red Garland, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones, is undeniable. They’re an impressive unit, and though the sessions were part of a marathon sequence of recording, nothing feels forced or overworked. They’re just… relaxin’. And while overall Davis would far surpass this release with more than a dozen of his Columbia releases, this is a solid release, and not a bad addition for anyone planning on starting a jazz collection.

Rating: 8.4 out of 10

Porgy and Bess

(1958, Columbia)

In the late ’50s and early ’60s, Miles Davis recorded a series of albums with noted arranger and conductor Gil Evans, who previously worked with Davis on the sessions that made up Birth of the Cool, and the most interesting thing about them, aside from the lush and massive production, is just how diverse these collaborations proved to be. They covered Brazilian and Spanish styles as well as showtunes, which provided the source material for Porgy and Bess. A reimagined jazz version of George Gershwin’s classic opera, Porgy and Bess is both a testament to the strength of the original songs as well as that of the musicians’ incredible performances. Intended to be heard as a whole, Porgy and Bess nonetheless works best when heard from start to finish, the flow and the drama of the album so carefully and brilliantly executed that, even with the words removed, the album remains strongly emotional and evocative. But, as with most of Davis’ classic jazz recordings, there are certainly some hefty standouts, chief among them “Prayer (Oh Doctor Jesus)”, “I Loves You, Porgy” and, of course, “Summertime.” Porgy and Bess is a very rich and detailed recording and it can take a few listens to fully absorb it all, but this is by no means an obstacle to enjoying it. It’s one of Davis’ most accessible releases, in addition to being an early highlight.

Rating: 9.0 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Amazon (vinyl)

Kind of Blue

(1959, Columbia)

Kind of Blue is easily the hardest album to write about in Davis’ discography, simply because it’s the kind of record that likely is already in the libraries of anyone reading this feature, a vaunted institution not only in jazz, but in the history of popular music. It’s Davis’ best-selling album, having been certified quadruple platinum in 2008, and ranked number 12 on Rolling Stone‘s list of the 500 greatest albums of all time. So it’s a big deal. And there’s a good reason for that. For starters, Davis’ choice to pursue “modal” improvisation, based around a series of scales rather than chord progressions, freed up the musicians to pursue more adventurous, and for that matter melodic, avenues through which to explore. This method, though not the first time Davis used it, set a new high standard for the genre, massively influencing much of what came afterward. And then, there’s the cast of musicians, all of whom give knockout performances, from pianist Bill Evans to saxophonist Julian “Cannonball” Adderly, to the great John Coltrane, whose solo in “So What” is a work of awe-inspiring majesty unto itself. And part of what’s unique about Davis as a bandleader is that he’s never an overbearing presence; he gives his musicians room to breathe, but when he does take his own solos, they’re always powerful and elegant, which hold true throughout Kind of Blue. Most importantly, Kind of Blue contains five perfect pieces, each of which is simultaneously expertly executed and extremely beautiful. It’s a perfect album, which is not something just any musician can achieve (let alone numerous times), and the kind of recording that can open someone’s eyes to a whole new world of music. As Q-Tip once said in an interview, “It’s like the Bible – you just have one in your house.”

Rating: 10 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Turntable Lab (vinyl)

Sketches of Spain

(1960, Columbia)

To fully grasp the importance of Davis’ collaborative works with Gil Evans, one needs to understand what “third stream” is. Essentially, the term “third stream” signifies a kind of music that exists somewhere between jazz and classical, and to a certain extent, this is the direction the two took for part of their prolific period of work together. In particular, Sketches of Spain marks their most beautifully ambitious work to combine familiar jazz tropes with the dramatic elegance and orchestral arrangements of classical music. On Sketches of Spain, Davis and Evans took inspiration from the Spanish folk tradition to create a big and triumphant album that is more jazz in aesthetic than practice. Improvisation is minimal on Sketches, its careful, compositional nature making it something of a unique selection in Davis’ catalog. It is, on one hand, a subdued record, one that soothes more than many of Davis’ albums up to this point. And yet it’s also a highly dramatic album, with punctuated bursts that keep it from ever being so politely pleasant as to fade into the background. The nuanced arrangements from Evans, not to mention the size of the orchestra, ultimately make Sketches of Spain the kind of album that, while great for atmosphere, asks a certain amount of attention from the listener. Each detail seems to draw you in closer, as each subtle movement reveals something new and captivating. Though Sketches of Spain does not have quite the reputation that Kind of Blue has in terms of introducing many to jazz or changing how they hear it, it’s nearly as well regarded and just as much of an artistic treasure.

Rating: 9.4 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Rough Trade (vinyl)

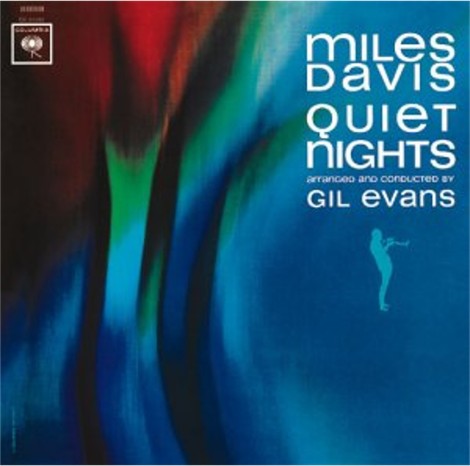

Quiet Nights

(1963, Columbia)

The last of Davis’ albums with arranger and conductor Gil Evans, Quiet Nights is largely considered the worst of their collaborative works, and a noble failure in general. That doesn’t mean, however, that it is a bad album. In fact, it’s quite pretty, but it’s incredibly short, and feels unfinished. There’s a good reason for this: in three recording sessions over the course of four months, Evans and Davis only rounded up about 20 minutes of usable material, and in order to pay for the large studio costs, producer Teo Macero added an extra track from an entirely separate session and handed over the product to Columbia to show their investment wasn’t for naught. Davis did not approve of the decision to release an unfinished project, and didn’t work with Macero again for another few years. Given all of this information, it’s easy to see why the album takes up an awkward place in Davis’ catalog, and for that matter, why it’s viewed as a disappointment. That said, it’s pretty enjoyable, and despite its shortcomings, has a handful of great tracks, most notably Davis’ take on Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Corcovado” (from which the album gets its title). The decision to take on Brazilian sounds like bossa nova was probably a record company trend chase, given its popularity at the time, and it’s understandable why Davis might not have been nearly as enthusiastic about that. But at its strongest moments, he knocks it out of the park. And at its worst, it’s merely pleasant. This is by no means a disaster, just a missed opportunity.

Rating: 8.0 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Amazon (vinyl)

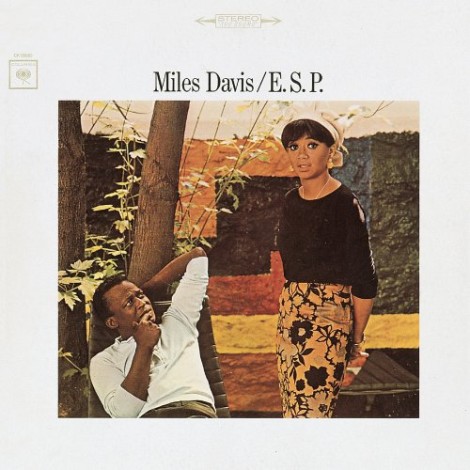

E.S.P.

(1965, Columbia)

Miles Davis made some remarkable contributions to jazz in the ’50s with his first classic quintet, but his second provided a new gateway to exploration and experimentation. In 1965, Davis’ first album with this second group (featuring Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and a 19-year-old Tony Williams) bridges his early ’60s hard bop output with the more avant garde direction he’d take later on in the decade. However, E.S.P., being the first outing with this quintet, is only a taste of what’s to come. That said, it’s a solid album. It runs the gamut from more avant pieces like “Eighty-One,” which blends melodicism with sharp, punctuated rhythmic complexity, and more laid-back cool pieces such as “Mood.” Things would certainly get much weirder from here on out, but E.S.P., named possibly for Davis’ uncanny ability to pick up a piece of music without having to practice, is a fine chapter in his discography.

Rating: 8.9 out of 10

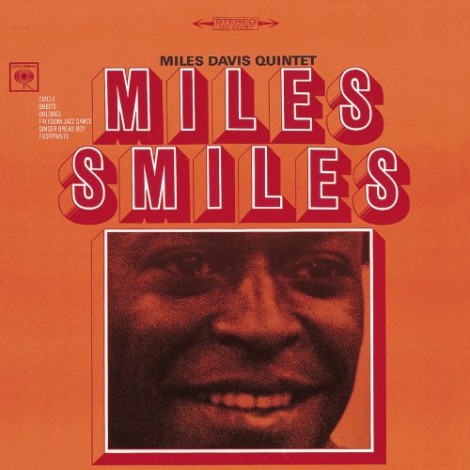

Miles Smiles

(1967, Columbia)

In 1963, Davis and Teo Macero had a bit of a falling out after the Quiet Nights fiasco, Macero having gone against Davis’ wishes and gave Columbia masters to an unfinished album to release as-is. Though the album was actually halfway decent, it wasn’t what Davis wanted, and in retrospect left lots of room for improvement, or at the very least some fleshing out. By 1967, however, Davis and Macero had patched up their professional relationship and worked together again on Miles Smiles. The album continues the vibrant path laid forth on E.S.P. but to slightly more successful effect. The dynamic between the quintet’s musicians is awesome, and there’s an undeniable energy to the sessions that’s infectious, though it’s certainly a step away from some of the more melody-heavy material from earlier in Davis’ career. A couple of numbers stand out in particular. First, opening track “Orbits,” penned by Wayne Shorter, takes the listener on the aural equivalent of a roller-coaster ride, with the quintet launching into one of the most invigorating tracks of their tenure. And the other major highlight, to my ears, is “Footprints,” another Shorter composition and the longest track on the album. It takes a good minute or so before the quintet begins to construct the groove that carries the song, but once they hit it there’s no turning back. It’s incredible.

Rating: 9.0 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Amazon (vinyl)

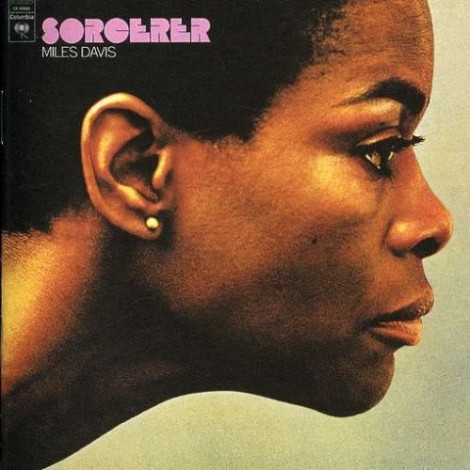

Sorcerer

(1967, Columbia)

The mid- to late-’60s run that Davis had with his second quintet is one that found the five musicians time and time again hitting a sweet spot, showing off a kind of mesmerizing improvisational language that translated in a series of great albums. Sorcerer, released in 1967, is certainly another worthy inclusion in the series, though compared to an album like Miles Smiles, it pales a bit. Sorcerer is a good album, definitely, and the amazing “Prince of Darkness” starts the record off on a very high note, its melodic swing, to my ears, an even greater achievement than most of the other songs the quintet recorded during the half-decade. But the remaining six tracks don’t approach such heights, rather maintaining a steady cool that’s enjoyable, if not one that leaves much of an impact. It does, however, have an odd, brief closing vocal jazz track, “Nothing Like You.” Though the thought of its inclusion seems nice in theory, cleansing the palate after a long jam session with a nod toward pop, it’s a little too goofy for my tastes. Good effort, but the execution leaves something to be desired. Still, Sorcerer provides an entertaining listen, if not a groundbreaking one, and even if most of the material doesn’t live up to his best, it’s worth a listen.

Rating: 8.2 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Amazon (vinyl)

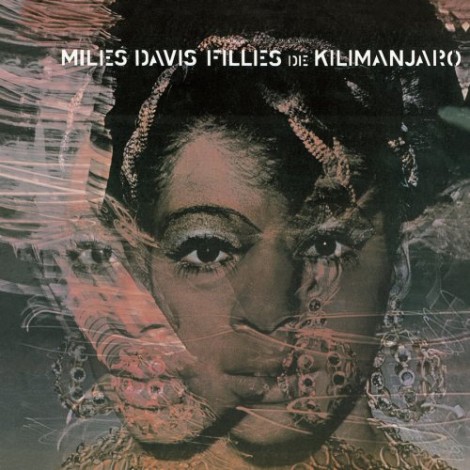

Filles de Kilimanjaro

(1969, Columbia)

It doesn’t seem quite right to use the word “underrated” when discussing a Miles Davis album, as a pretty massive chunk of the man’s discography has been celebrated for decades. And yet, I can’t help but lob such a word at Filles De Kilimanjaro, an album that stands as an important transition between his work with his second quintet and his electric fusion period, which would begin later that same year with In a Silent Way. Bearing one of Davis’ coolest cover images (which depicts a psychedelic vision of Davis’ funk-queen wife Betty), Filles does not quite stretch out into the bold and sprawling electric sounds that In a Silent Way pioneered, but it does begin to incorporate some of the elements that made that album such an eye-opener. Keyboardists Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea each play electric piano, for starters, which lends the album a warmer groove. And Ron Carter plays electric bass during the portions on which he is featured. Additionally, Davis subtly introduces elements of rock, which hadn’t been a major part of his work before, particularly on “Mademoiselle Mabry (Miss Mabry)“, which is, very loosely speaking, based on the melody to Jimi Hendrix’s “The Wind Cries Mary.” That and the title track, which comes immediately before it in sequence, are the two true stunners on the album, each lengthy and gorgeous, but the album as a whole works beautifully, showing off some more experimental elements while retaining a kind of grace that marked many of Davis’ great records of years prior. This is essential, and highly underrated listening, and I’m sticking to that.

Rating: 9.2 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Amazon (vinyl)

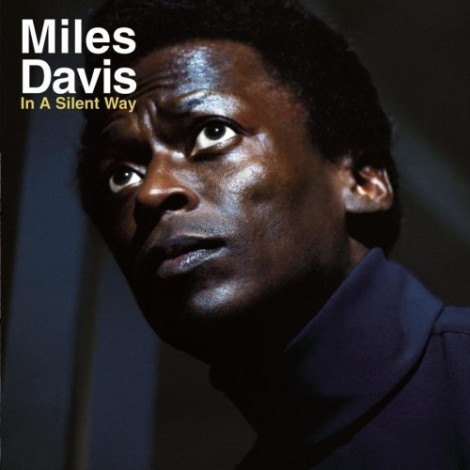

In a Silent Way

(1969, Columbia)

I saved In a Silent Way to be one of the final Davis albums I personally evaluated, even though it’s squarely in the middle of his career, time-wise. Historically speaking, it’s a massive milestone for Miles Davis, sounding the opening bell for what would be a fruitful period of electric jazz-fusion. Where, previously, Davis had been playing a complex style of hard bop that was primarily rooted in acoustic instruments, In a Silent Way took a big step forward by incorporating effects-laden electric guitars, keyboards, bass and studio techniques that pushed the sounds on the album outside the more familiar characteristics of jazz and into something much more psychedelic and weird. Further adding the album’s importance was producer Teo Macero’s editing techniques, which found him re-editing the album’s two lengthy tracks, “Shhh/Peaceful” and “In a Silent Way/It’s About That Time,” to create a unique musical narrative. This, at the time, was unheard of in jazz recordings, but Davis would only grow to become an even greater provocateur with time. On a personal note, In a Silent Way, for me, stands as Davis’ greatest triumph. It’s not his weirdest, nor his most melodic, nor his most commercially successful album. But it is the moment at which his experimental side and his more melodic tendencies converged into a work of sublime harmony. Hearing this for the first time was eye opening, to say the least. I didn’t know that music could be so nebulous and dense, yet also so beautiful. Everyone has their opinion about which of Davis’ albums is the most important, the most interesting, or simply the best. In a Silent Way manages to check off all three.

Rating: 10 out of 10

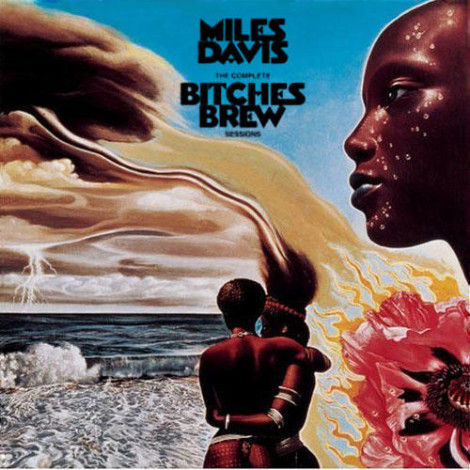

Bitches Brew

(1970, Columbia)

Miles Davis’ first album to be released in the 1970s, Bitches Brew, is not coincidentally also an album that marked a clear separation from everything released prior, save for In A Silent Way, in which Davis planted the seeds for the bold, noisy and alien sounds that he would create on a series of groundbreaking albums soon thereafter. Bitches Brew is the most notable of his ’70s output, and, in my opinion, one of his best three albums, ever. The first time I heard it, a switch went off in my head. I liked it, but I wasn’t sure why. This was bizarre music, which at times seemed chaotic and overwhelming, but by no means directionless. Over 94 minutes, Davis and a huge cast of musicians set forth on a musical journey that changed music forever. And that’s no exaggeration. Bitches Brew was not just a huge leap forward for jazz music, but for rock `n’ roll as well. During his “Electric” period, Davis took many cues from rock music, and the rough, abrasive nature of rock shows in many of the pieces he recorded in this timeframe. While On the Corner ultimately stands as Davis’ most controversial record, this one isn’t far behind. Tracks like “Pharaoh’s Dance” don’t seem grounded in any earthly music I know, while “Miles Runs the Voodoo Down” and “Spanish Key” take that space age freakout and make it funky. The album’s overflowing personnel count was recently the subject of a particularly hilarious edition of Christopher Weingarten’s “Are You Smarter Than a Rock Critic” in the Village Voice, in which one respondent answered that Weingarten’s mother played the skin-flute. But the cast on Bitches Brew is as strong a cast of musicians as you’ll hear on any jazz recording: Dave Holland, John McLaughlin, Chick Corea, Wayne Shorter, Larry Young, Joe Zawinul, and Bennie Maupin, whose ominous bass clarinet casts its own interesting shade of dark over the album. Davis aimed his raygun at the conventions of jazz on Bitches Brew, and the genre hasn’t been the same since.

Rating: 10 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Turntable Lab (vinyl)

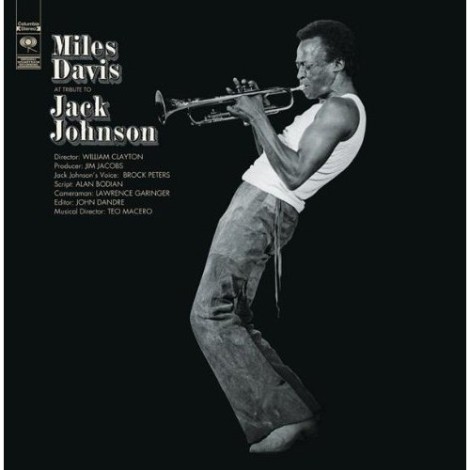

A Tribute to Jack Johnson

(1971, Columbia)

Miles Davis once promised to form the “greatest rock band you ever heard.” It’s important to note that his definition of rock is probably different than most people’s, but for most of the ’70s, rock ‘n’ roll played a huge part in the direction he took. With A Tribute to Jack Johnson, named for the famous boxer, Davis and a wide cast of supporting musicians (including John McLaughlin, Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, Jack deJohnette, Dave Holland and Sonny Sharrock) came closest to fulfilling that promise with a set of two 25-plus minute epics that take dense, rocking grooves into brave and exploratory territories. And the dirtier, crunchier of the two, “Right Off,” was born essentially of a jam that started while the group was waiting for Miles. McLaughlin started playing a dirty, funky riff, and within two minutes, Davis rushed in and joined the session, playing one humdinger of a solo, a passage of music that stands as one of his most transcendent. That this wasn’t so explicitly planned, at least if the stories are to be believed, goes to show just what kind of magic was possible in the studio at any given time. Flipside “Yesternow,” meanwhile, is a bit more all over the map, in a good way, of course. It starts off with a funky, James Brown-inspired bassline before incorporating a section of Davis’ “Shhh/Peaceful” from In a Silent Way as well as a few other of Davis’ past compositions (even a sliver of “Right Off” as a matter of fact), and ultimately into a dense ambience, closed out with the sound of Jack Johnson, as voiced by actor Brock Peters. This is a rock album and it isn’t a rock album. And even among Davis’ fusion albums that were so prevalent at the time, Jack Johnson occupies kind of a weird space. Yet that merely makes it stand out that much more, an incredible lightning bolt of spontaneity and inspiration, and the kind of album that changes the way we hear music.

Rating: 9.2 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Rough Trade (vinyl)

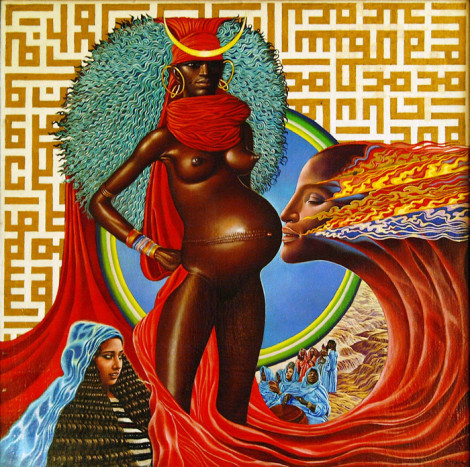

Live-Evil

(1971, Columbia)

The general rule with `Celebrate the Catalog’ is to evaluate studio albums only, so including Live-Evil here breaks that rule, but only in part. It’s an album, much like its title would suggest, that contains a hefty amount of live material. But it’s also broken up by a few shorter studio-recorded pieces, which represent a different side of Davis’ musical direction at the time. And, in fact, Davis even conceptually packaged the album with opposing front and back album art depicting a pregnant woman on one side to represent life and birth, and a gross-looking creature on the other side to represent evil. From there, however, the two sides seem to blur a bit, because there are a good many live moments that sound more `evil’ than the studio tracks. In fact, the studio pieces, like “Little Church” and “Selim” (Miles spelled backward) are actually quite pretty ambient pieces that show off an ethereal complement to the nastier fusion funk of the longer live pieces. But boy, those live jams sure do cook. “Sivad” (Davis spelled backward; you see a theme developing here) wastes no time getting to a groove, laying down 15 minutes of dirty rhythms that breeze by surprisingly quickly. Bear in mind, 15 minutes on this release is relatively short, particularly when held up against “Inamorata and Narration,” which pushes well past 26. That track in particular, however, is the true stunner, capped with a super cool, trippy narration at the end. Reportedly, during the time these recordings were made, Davis was in extremely good shape, spending a lot of time working out and avoiding drugs, despite how fucked up some of these sounds are. And he’d have to be in good shape to manage some of the performances he does here. The thought of it makes my lungs hurt. Though Davis adds filter effects to his trumpet as well, treating his instrument in much the same way Hendrix did his guitar (save for the fire). Still, guitar is actually the most prevalent instrument here, so despite Miles’ helming of the proceedings, this is almost as much John McLaughlin’s album as it is Davis’.

Rating: 9.2 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Amazon (vinyl)

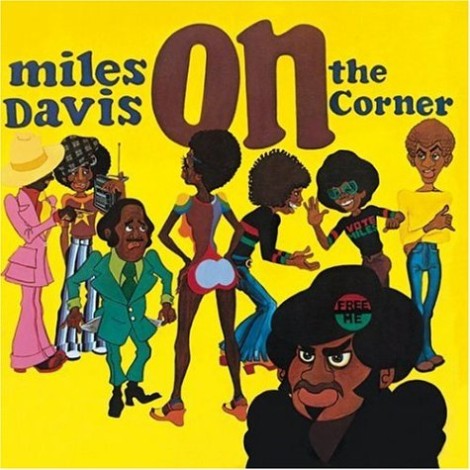

On the Corner

(1972, Columbia)

Google “Miles Davis controversial album” and this is what comes up, over and over and over again. It seems kind of odd, in retrospect, that On the Corner, and not any of his numerous prior forays into fusion, rock, jazz or other experimental realms, is the album of his that pissed off fans most. But here’s why it did: On the Corner is a funk album. It’s not a funk album like The Meters, or like Funkadelic even, though they’re a much closer analogue. It’s Miles’ own dirty, nasty and raw take on funk, and even among his wilder fusion records, it’s in a category of its own. Despite how fucked up it may have seemed at the time, however, On the Corner has gone down in history as a classic. Here, Miles teams up with five drummers, legendary keyboardists Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock, guitarist John McLaughlin and a cast of other chaotic co-conspirators and just goes wild. And for the first half of the album, track separation is entirely irrelevant; the whole of the “On the Corner” suite is one long piece of music that flows and grinds and squeals as one beastly organism. That it’s noisy, discordant and confrontational certainly adds to the mythology about it being offensive to the sensibilities of more refined listeners, but it’s also what makes it an essential. On the Corner is Miles & Co. not giving one-tenth of a shit, and it grooves that much harder because of it.

Rating: 9.5 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Amazon (vinyl)

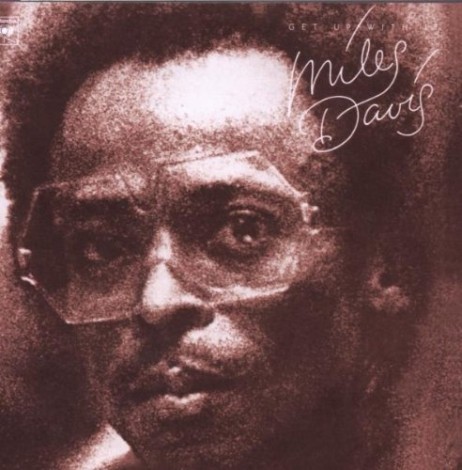

Get Up With It

(1974, Columbia)

Get Up With It, released in 1974, stood as the last complete album Davis would release before taking a six-year hiatus. The time away from music not only served as a means of artistic breather, but recuperation as well, with a variety of health problems afflicting the jazz legend. He did, however, close out his fusion era with a massive statement, however, this two-LP beast of a thing that was not just long for an album, but bordering on triple-album length. And, as this was a closing bookend to his fusion period, Davis filled these two-plus hours with weird, truly space-age alien funk that was simultaneously more commercial than On the Corner and a lot more bizarre. Where that album was full of gritty, grimy, greasy, down ‘n’ dirty funk, this album is off in another galaxy. However, it is quite stunning in parts. The opening, 30+ minute masterpiece, “He Loves Him Madly,” is the most intriguing and beautiful piece, a tribute to Duke Ellington, who had died shortly before the track’s recording. It’s much more spacious and atmospheric than much of Davis’ other fusion-funk recordings, and actually served as a huge inspiration for Brian Eno’s ambient works. On the other side of the spectrum, “Red China Blues” is a surprisingly straightforward blues track, spanning only four minutes, with a full brass section and harmonica. It’s a bit of an odd selection among much more freaky pieces, but a lot of fun all the same. The remainder of the album delves into accessible yet disorienting funk jams that maintain a cool, interesting sound, and, on “Rated X,” even sound a bit terrifying. But none of them quite live up to the massive achievement of “He Loves Him Madly,” and how could they? Still, exhausting as this is, it’s a worthy selection and a solid ending to Davis’ fusion era.

Rating: 9.0 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Amazon (vinyl)

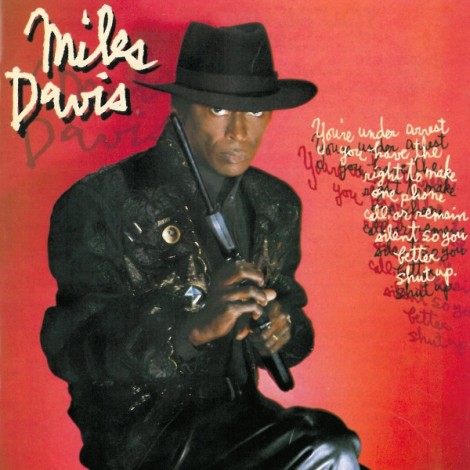

You’re Under Arrest

(1985, Columbia)

For a pretty big chunk of the ’70s, Davis shied away from recording and performing in public due to his deteriorating health. Among his various ailments were ulcers, arthritis (for which he underwent hip surgery) and cocaine addiction, so, needless to say, Miles was in pretty bad shape. But following several years of recovery, Davis got back into the game, and ended up delving into a variety of new directions in his final decade on earth. Unfortunately, not all of his instincts were worth following, and as a result, You’re Under Arrest stands as one of his most ill-advised releases, at least from an artistic standpoint. Certainly, it proved commercially successful, and the fact that the album contained some glossy covers of Michael Jackson’s “Human Nature” and Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time” undoubtedly contributed to that. But whatever commercial success it enjoyed doesn’t erase the fact that it’s a portrait of Miles with all the innovation and soul removed. It’s an album steeped in dated, glossy ’80s production values and lite-jazz fluff. Only the opening track’s new wave funk and the closing medley’s ambiance provide any redemption from the marshmallow goo that permeates this album’s every corner, and even those tracks are pretty forgettable. This may very well be Davis’ worst album (some would argue Decoy is worse), but considering the sheer number of highly influential, groundbreaking and just plain amazing recordings he put out in his time (look at all those 9s and 10s), this sore spot doesn’t sully his legacy all that much.

Rating: 3.5 out of 10

Listen/Buy: Spotify | Rough Trade (vinyl)

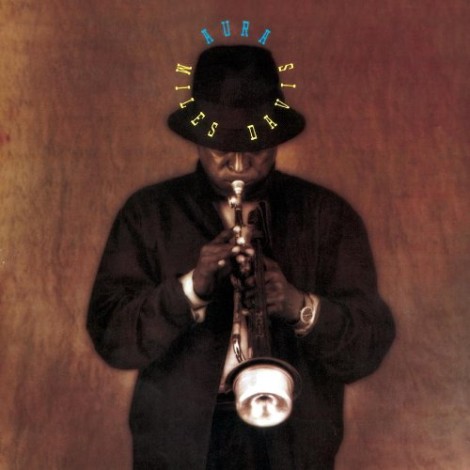

Aura

(1989, Columbia)

I chose to close this edition of Celebrate the Catalog not with Davis’ last album, and I thought it a bit too harsh to leave on a disappointing note (but it is important to note that even geniuses make mistakes). Rather, the most logical place to close out Miles Davis’ most memorable works is with Aura, the final album he recorded for Columbia before heading to Warner Bros. Recorded earlier in the decade, Aura didn’t see release until 1989, as Columbia wasn’t sure what to do with it. Taking into account how many weird and “difficult” records Davis released in his lifetime, it’s no small feat to give the label something they were hesitant to put out. But, even among some of Davis’ more out there material, Aura is an odd one. The story goes as follows: the album is essentially a ten-part suite composed by Danish flugelhornist Palle Mikkelborg, with its titles taken from the color spectrum, and based around a series of notes taken from the letters in Miles’ name. The music itself, meanwhile, is not so much jazz but a combination of varied sounds, from modern classical to ambient and rock. The works of Gil Evans play a major influence on this album, and it can be heard in the brassy bursts of tracks like “Yellow,” which turns from eerie to ominous by its fifth minute. Yet, meanwhile, “White” is spacious and minimal, revealing an elegantly oblique side of Davis’ musical persona. Some of it, most notably “Intro,” is a little off-putting, and a little dated. But by and large, the minor bits of fusion that don’t quite work aren’t enough to overshadow the prettier avant garde pieces.

Rating: 7.5 out of 10

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.