With On the Corner, Miles Davis rewired jazz

In 1972 Miles Davis released On The Corner— at the time one of his most poorly reviewed, ill received and least popular albums. Full of extended grooves, wah wah effects, synthesizer squeals and boundary pushing sense of urgency, it plays like a psychedelic head trip beyond anything resembling traditional jazz.

There are early examples—In A Silent Way in 1969 and Bitches Brew in 1970—that signaled the arrival of his fusion period, a lane outside the canons he’d already mastered, like bebop or his pioneering cool. Electronic instruments replaced acoustic arrangements, styles coalesced into one another and composition became a piecemeal process by way of studio editing.

By the time he arrived at On The Corner the reserve of his previous fusion efforts became an after thought. Even 50 years on, it’s not only cutting-edge but unequaled. The sound of Miles Davis weaving notes from his trumpet—wailing and purring—through a backdrop of electric guitars, Fender pianos and rubberband basslines, results in an almost hour’s worth of music like nothing else before it.

That’s not exaggeration—even his approach changed the landscape. His methods, sign posts, carving out a path for contemporary electronic music, with production techniques that still make sense, like cut and paste assembly—before DAWs like Ableton, Pro Tools or Logic.

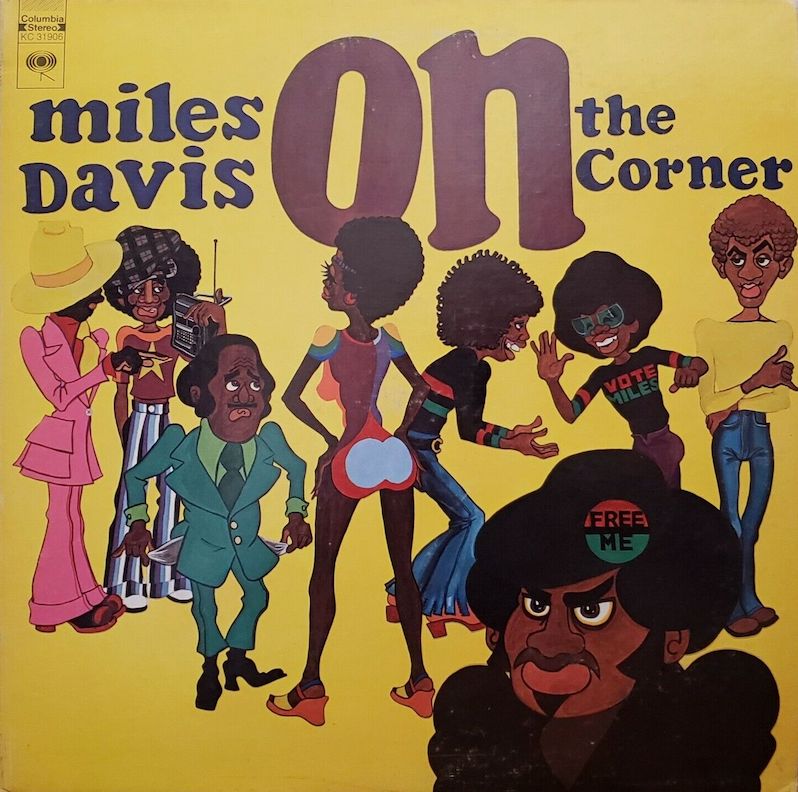

It’s a full “tech” leap, the future on arrival, in the sense of circuitry and conduits but musically as well. From the technology of funk to the science of tape, On the Corner is visionary. And while it’s an album that’s in many ways undefinable, as it relates to genre, one of the most appealing aspects, for work so daring, is that it’s easy to listen to. A Blaxploitation soundtrack on acid—Shaft dosing, ya dig?

The spirt is primal, root chakra oomph. Mood and tension push and pull as the album pulses and throbs—a complete commitment to rhythm. The music’s density, in some ways feeling like a tip of the hat to the ideas of saxophonist/composer Ornette Coleman. A free jazz vanguard who Miles Davis dismissed early on, his harmolodic theory possibly too far out for even Davis when it was first introduced. Here though, some of those concepts—equal value given to rhythm, harmony and melody—are applied. A reevaluation, a nod—indeed, Ornette was on to something.

Input is only as good as its source material and in addition to what he may have drawn from the Harmolodic premise, there are other ancillary reference points. The tenets of acts like Sly And The Family Stone, James Brown, arranger Paul Buckmaster and electronic composer Karlheinz Stockhausen—kaleidoscopic soul, “playing from the bottom of the band” and notions of space—are also distilled through the maestro.

From jump the album smolders, seemingly starting out of nowhere, percussion and hi hats, a looping groove then horns, solos and swagger. There are moments when the music slows down, crawls even, but the majority of the song is spent in high gear. The energy free burning and pocket protracted, Sir Miles leading his band, vibing. His usual timbre is still recognizable, albeit drenched in wah wah, feedback and warp. Presenting his horn in a modern context, as if to suggest that since guitars and pianos can go electric—trumpets can plug in too.

Forty-six years old at the time of its release, Davis was looking to court a younger audience. One that had been raised outside the juke joints and small cafes that favored organic jazz. The new, new—On The Corner wasn’t created with the conservative listener in mind. This is a progressive orbit, a forward facing LP.

It’s a world unto itself, supernatural — alien. Like, how on earth did the artist who created the aesthetic of ‘cool’, arrive here? Fusion free-form, laced in sitars and reverb, funk riffs and toe tapping runs. He’d altered things before, shifting the direction of sound. And this was another one of those moments. A project of demarcation, before and after, the separation between his own acoustic history and an emerging desire for amplification. He wasn’t interested in back sliding, the ties to the past no longer in play: style, taste, rules—all up ended for the sake of innovation.

No man is island, though. And Davis had co-conspirators. As an army of musicians, almost two dozen, contributed to the OTC sessions. With quite a few heavyweights among them, Herbie Handcock who’d go on to release Head Hunters a year later in 1973—his own fusion high water mark and stamp on the period. Chick Correa, a giant of a pianist with a decades long career highlighted by more than 70 Grammy nominations and 21 total wins. Then there’s James Mtume who played percussion in Miles band and on the album, before forming his own group, Mtume which struck pay dirt in 1983 with the release of the hit single “Juicy Fruit.”

Mentor, virtuoso, icon—no doubt. A legitimate original who left us this groundbreaking game changer. An album ahead of everything, even critics’ ability to understand it, that after further review and significant time, has received the proper recognition it deserves. A standalone in a standout catalog, On the Corner is the sound of brilliance caught on tape.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

J. Smith is a Golden State native, long time rap fan and music enthusiast

Thank you J.Smith. It’s always a pleasure to see other people’s appreciation of OTC. Duke Ellington said that Miles Davis was the Picasso of jazz. I like to think that was misreported and that he actually said Picasso was the Miles Davis of art.

A brilliant piece of music and so nice to lose yourself in. Thanks for the reminder!