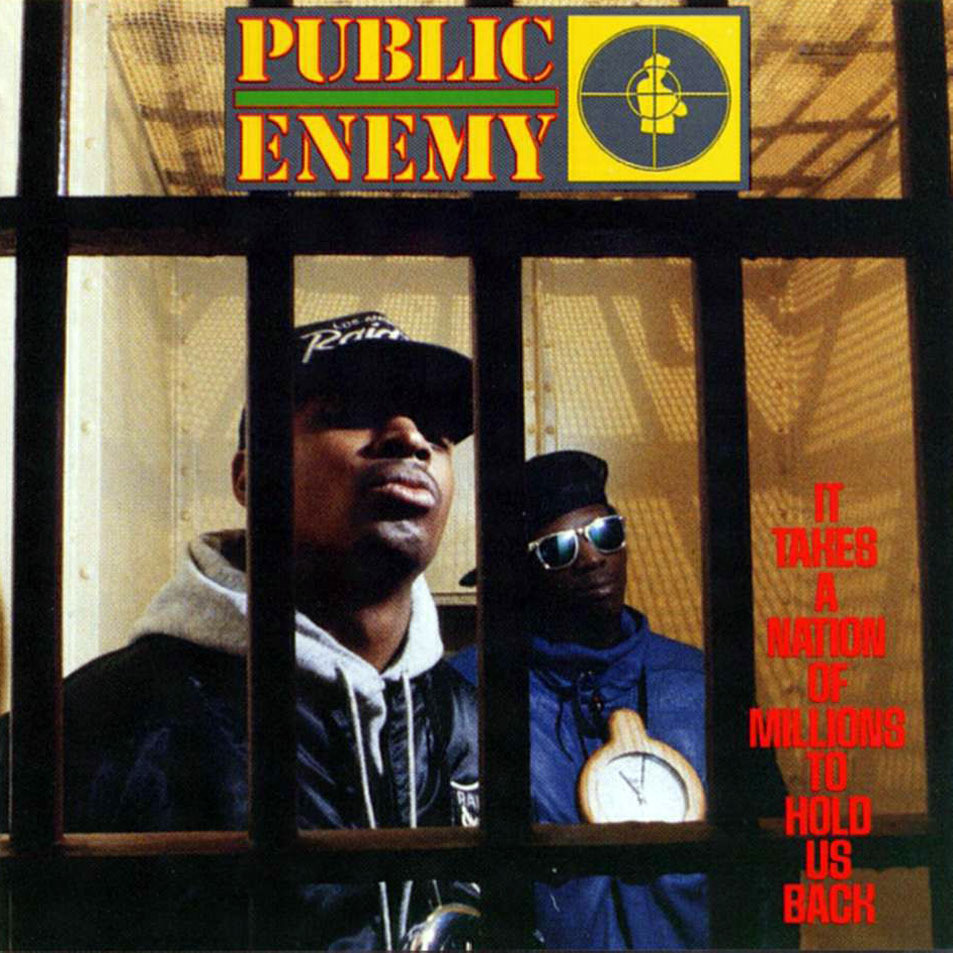

Public Enemy’s It Takes A Nation of Millions To Hold Us Back changed the shape of hip-hop

To understand the importance of Public Enemy‘s It Takes A Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, one has to take a step back to 1987. LL Cool J’s “I Need Love” was the biggest rap song of the year. Eric B. and Rakim’s Paid in Full was minimally an outlier for the balance of the genre, which was interspersing tedious ’80s party rhyme with soon-to-be-tedious street hustler anthems, such as with albums like Boogie Down Productions’ Criminal Minded, N.W.A. and the Posse from a young N.W.A. Kool Moe Dee’s How Ya Like Me Now, Ice-T’s Rhyme Pays, Heavy D and the Boys’ Living Large and Too Short’s Born to Mack. Many of those are inarguably classic albums. None, however, could have given hints to the sea change Public Enemy would bring in 1988.

On the political front, the United States had just fully taken in the Iran-Contra affair and the campaign of doomed presidential candidate Michael Dukakis was busy torpedoing Joe Biden’s election hopes, although it proved to be so inept it would fail to stop even George H. W. Bush, badly damaged by his association with Iran-Contra, from his White House aspirations the next year. The War on Drugs was still in full swing and the country had been marred by racial conflagrations that would seem almost foreign to those born after 1990. Music was reflecting many of these tensions, to which the Universal Zulu Nation would prove prescient. The era’s spate of issues would prove fertile ground for what would become Public Enemy’s magnum opus, celebrating 30 years in 2018.

Amid the social tumult of 2018, the album that is part of the canon of hip-hop’s Golden Era and is unquestionably one of rap’s most political releases ever is required listening not just by informed hip-hop lovers, but for any student of contemporary sound.

The story of college friends Carlton “Chuck D” Ridenhour and William “Flavor Flav” Drayton and their connection with the Shocklee brothers and Eric “Vietnam” Sadler, as well as Professor Griff and Terminator X, began in the eyes of the public in 1987. The collective’s promising though underwhelming debut made It Takes A Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back particularly stunning. Public Enemy’s mainstream introduction came with Yo! Bum Rush the Show, a record rooted in the group’s nascent political evolution. However, though Show was forged by some of the era’s major racial flashpoints, such as the New York police murder of Michael Stewart and the Howard Beach riots, it was a product of the time. What ended up Show‘s sole hit was something that felt very 1987: “Public Enemy No. 1,” brimming with the hi-hat beats popular at the time and the MC Flav affectionately called “Chuckie D” rapping about “the fly girls [wanting] my photo.” Indeed, Show was far less political than the New York Times played up upon release; for the moral-heavy “Rightstarter (Message to A Black Man),” there were the pedestrian boasts of “Muzi Weighs A Ton,” “M.P.E.,” “You’re Going to Get Yours,” “Too Much Posse” and “Raise the Roof,” as well as the song that would come back to haunt them later, “Sophisticated Bitch” (PE would pen “Revolutionary Generation” as an apology of sorts on 1990’s Fear of A Black Planet). Its Wikipedia entry positions Show as a critical success, but numbers don’t lie and the album peaked at no. 125. Sadler and the Shocklees, soon to rise to fame as the Bomb Squad, headed right back to the studio with Chuck and Flav to compose Nation.

In 2004, Rolling Stone named Public Enemy no. 44 on its list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time. It was the highest seeding of a hip-hop performer. The influence of Public Enemy years later on popular music and of its sophomore album, It Takes A Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, undoubtedly was key to such a showing. Stylistically, Show and Nation were seismically divergent in their sound and approach. Look no further than the gentle funk in the Meters sample on Show’s “Timebomb” next to Nation‘s fraught “She Watch Channel Zero?!,” which features the instantly recognizable riff from “Angel of Death” by Slayer. Where Show was steeped in soundscapes that were unique yet derivative (the minimal beat of the acidic “Megablast” could have easily been a Side B backdrop on LL’s stellar Bigger And Deffer, from whence “I Need Love” came, for instance), with Nation, the Bomb Squad went all in on making music unlike anything out there. Chuck D has recounted in many retrospectives how much he hated what he heard initially. Yet Sadler and the Shocklees were more omniscient than they had been given credit for. As Chuck’s lyrics became sharper, the production got more capricious, a Bonnie to his Clyde that Flav never could be. Air horns adorn the claustrophobic haze of sound, anxious percussion spikes the punch and mangled samples propel a foreboding atmosphere that, as Chuck would later remember, made people go berserk.

Nation begins with the concussive “Countdown to Armageddon,” capturing PE in a setting where its members have become legends: the live stage. Even now, you can find many live Public Enemy albums, many of which are performed with a band and without voice tracks. Chuck D’s latest project, Prophets of Rage, may be maligned as a Rage Against the Machine cover band, yet the concert setting is one that seemingly always suited him. Nation opens with a reminder that PE has always been at home with a crowd.

In less than two minutes, Nation introduces the voice of civil rights firebrand Malcolm X, whose words “too Black, too strong” come from a 1963 lecture, “Message to the Grass Roots.” References to X, Rev. Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam, Assata Shakur (referenced by her legal name, Joanne Chesimard, in the wrenching “Rebel Without A Pause”) are sprinkled throughout Nation and this first full track, “Bring the Noise.” The frantic pace of “Noise” boasts several samples, including songs by the Commodores and Funkadelic, and James Brown’s “Funky Drummer,” but it’s Chuck’s retooled flow that is the real star here. Gone is that lazy, summertime delivery of “Public Enemy No. 1.” What replaces it is the microphone command that put Chuck D and company in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame—seething, in your face and demanding of your attention. It was a vocal style unlike so many other MCs of that period; rather than that laid back style of Kane or the technical, elegant flow of Rakim, Chuck became rap’s Phil Anselmo, with that raspy voice, telling you shit’s not good in the most savage way possible. The songwriting on “Noise” is altogether different too. Show‘s copious cuts about the crew’s prowess are obliterated in favor of the radicalism the album promised, blasting the police, media and racism in rock music, name-checking LL Cool J, Yoko Ono, Anthrax, Run DMC and others, and rhyming political slogans like “power to the people” over a dizzying production of sound. Buh bye PE circa 1987. Hello immortality.

Few big-time rap songs can claim inspiration by linguist and intellectual Noam Chomsky. The crystalline “Don’t Believe the Hype,” the second full track on Nation, is one of them. With squealing horns, samples from Melvin Bliss (“Synthetic Substitution”) as well as Whodini, Juice and more, and Chuck’s most quoted lines (“a follower of Farrakhan/don’t tell me that you understand, until you hear the man“; “writers treat me like Coltrane, insane“; and “reach the bourgeois and rock the boulevard” among them), “Hype” went on to be one of Nation’s hits. It also remains a deceptively complicated song, where the production sounds minimal, yet the details ensure it is anything but. Like “Noise” and the reverberating “Caught, Can We Get a Witness?,” the media and music industry are targets. Such rows would pre-date PE’s clashes following the release of Planet and Apocalypse 91: The Enemy Strikes Black as well as the brief dissolution during that moment.

Nation‘s musical or humorous interludes (“Mind Terrorist,” “Cold Lamping with Flavor,” “Show ‘Em Whatcha Got” and “Security of the First World,” which would later be embroiled in controversy as the reputed base of Madonna’s 1990 hit “Justify My Love”) are among the few concessions Public Enemy makes on the album to hip-hop of this period. One of the other nods to trends, talking up one’s DJ in a rhyme, turns into a rant about equity. Moreover, Public Enemy frames attempts at doubt in another lens. On the spastic “Terminator X to the Edge of Panic” Chuck rhymes, “Who gives a fuck about a goddamn Grammy?/Anyway and I say the D’s defending the mic/Who gives a fuck about what they like, right?/The power is bold, the rhymes politically cold/No judge can ever budge or ever handle his load.” “Panic” introduces an accusation not heard in hip-hop before: You don’t like my DJ, not because you think he’s bad or yours is better—you don’t like him because you hate his politics.

Original buyers of Nation and those now who find the album on vinyl and cassette may note that Side A’s tracks tended to be Public Enemy’s more punchline-rich hits, particularly “Noise” and “Hype.” Side B featured songs that were complete stories or narratives: “Zero” was an uncomfortable take on a woman fulfilled by television, the noisy “Night of the Living Baseheads” a paean to drug addiction and dealers in African American communities and “Party for Your Right to Fight” on Black liberation movements. The climax of this storytelling, fittingly at the center of Side B, is “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos,” a story about a prison break by a conscientious objector. Fans new to PE will have to be discerning, as “Chaos” has, in fact, an alternate version on some albums that removes the second verse. The original version clocks in at six minutes and has a second verse that starts with, “don’t you know, they got me rotting in the time that I’m serving.” While “Rebel ” and “Prophets of Rage” would tap the more couplet-oriented spirit of Side A, they would later become some of PE’s best loved songs as well.

The flurries of anger captured in the spirit of the album, even 30 years later, might overshadow just how experimental the Bomb Squad’s spectral endeavors were at the time. Songs like the hell-raising “Louder Than A Bomb,” with its delicate open (birds!) into a crescendo of corrosive beats, the heavy metal sampling on “Zero” and use of stereo technology for individual vocals on “Party” were revolutionary in 1988 and would be put into practice by popular music performers decades later. A constellation of acts cite Public Enemy as a direct inspiration, while others surely saw indirect influences. Though many weren’t born on its release, It Takes A Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back may be one of the few hip-hop records we have all heard, in one form or another.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.