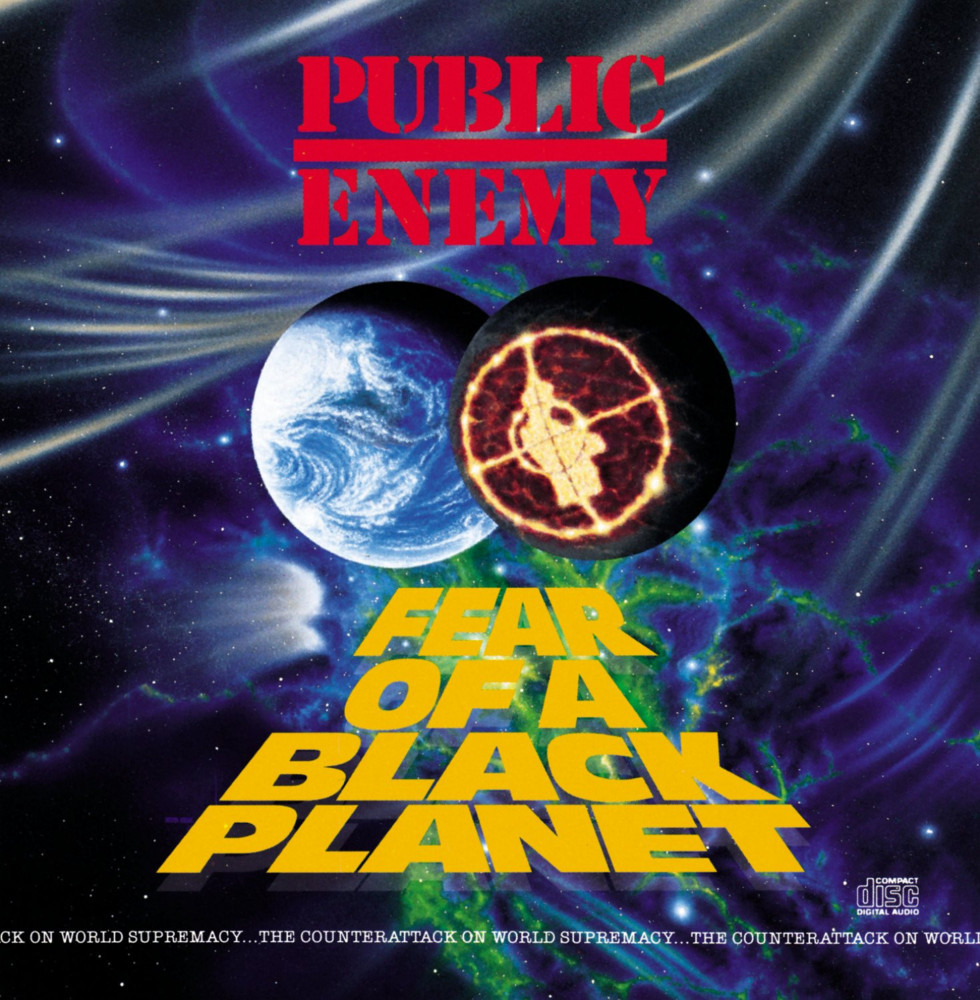

Camera and crystal ball: Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet at 30

Public Enemy’s rocket ride out of Long Island followed a clear plan, even if it seemed like an ad hoc one at the start. For all of its aggressive politics and sound, Yo! Bum Rush the Show in 1987 found Carlton Ridenhour (Chuck D), William Drayton (Flavor Flav), Norman Rogers (DJ Terminator X), and their Shocklee/Sadler production team (The Bomb Squad) essentially rapping stories of local crews corners, and parties. With It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back the next year, Chuck D demanded listeners fall in line and help PE track the spread—out of the neighborhood and across America—of foibles of and frustrations with racist systems.

A Model UN nerd and a scrawny choir geek, I wore a particular badge of pride being a Public Enemy fanboy in high school. I once fell asleep on a field-trip bus with Nation of Millions cranked to 11 on my Walkman. I seemed to be the only one in my endlessly white classes playing to Chuck D’s Damoclean type: the unmelanated embodiment of everything he was fighting against, and proof to PE and Columbia Records that his rebellious rhymes could find acceptance beyond “urban” audiences. And then, as junior year became senior year, Fear of a Black Planet was unveiled as the third and final piece of this puzzle.

Shifting Public Enemy’s focus from dominating American charts to dominating global conversations, Fear of a Black Planet reflected on worldwide reaction to both the band and their pet issues. Even the LP names suggested this expanding vision, from a “show” album to “nation” and “planet” ones. Topical as few rap releases before had cared to be, it thrust the performers, the posse and their posturing into a hot and relentless spotlight of Caucasian rage accented by occasional Black tut-tutting. And this album, of all albums, turns 30 this year, of all years.

Fear of a Black Planet was steeped in Chuck’s study of the “color confrontation” theory of Frances Cress Welsing. Credited with some of the earliest known psychoanalysis of racism, the Washington, D.C. Afrocentrist researcher posited that a lack of melanin in the skin is a genetic malformation, and people who have less of it react violently in the presence of those who have more. It’s not so much that prejudiced acts against people of color are products of white power structures or even beliefs—she proposed whites are simply predisposed to such acts. If ever there was merit to this, we might see it today with the application of Charles Krauthammer’s term “derangement syndrome.” People were/are paranoid over the political works of the Bush 43 and Trump administrations; derangement over Barack Obama’s existence as a Black politician and ascendance to a Black Presidency were collectively far more threatening to, and threatened by, white people.

Nation of Millions merely poked the polar bear of white supremacy; Black Planet threw rocks at it. This LP was the endpoint of half a decade’s worth of doubling down on the concept of being uncomfortable. There was journalists’ and academics’ discomfort with Chuck and Flav’s messages, and the band’s discomfort with criticism over affiliations with Louis Farrakhan and the Nation of Islam. In a time when political consciousness felt not as nuanced as today, nor nearly as aware of problematic affiliations and what to do with them, listeners like myself gritted teeth through PE’s brushes with anti-Semitism. Band member Professor Griff was fired, rehired, and demoted over it all; Chuck briefly broke up the group in frustration only to reform it once cooler heads prevailed. Where Chuck has called the lead-up to Nation of Millions “angering,” the space and time immediately after that was “humbling.”

Public Enemy worked out this frustration in plain sight by interpreting it in the first five tracks of Black Planet, 17 of hip-hop’s most relentless minutes. Terminator X and The Bomb Squad (including Carl Ryder, Chuck D’s other pseudonym on production) opened the album with fascinating plunderphonic experiments and three of PE’s defining songs. They painted a sonic Guernica with the likes of Prince and Parliament, a massive canvas of layered, distorted boom-bap frequencies to stand your hair on end as samples dipped in and out of mono channels. Chuck and Flav traded dialogue with Mikey Dread and Eddie Murphy, and went meta by arranging audio from past singles and clips from interviews with them and critiques of them. This covered their own controversies (“Welcome to the Terrordome,” “Incident at 66.6 FM,” “Contract on the World Love Jam”), pivoted back to their ability to highlight societal issues in Flavor Flav’s sad-clown classic “911 is a Joke,” and even imagined a more empowered future—in 1995—with “Brothers Gonna Work It Out.”

The album is loaded with curtain-jerking truths made clear to Chuck D during his radical childhood, to Flavor Flav in a life detoured through the penal system, and to Griff through extensive research. The issues and practices discussed may have sounded jarring to listeners when Black Planet first came out. In this long spring and summer of protest it feels like a whole flock of chickens coming home to roost, and we find modern twists on what PE first presented as “our history/not his story.” For example, the musical tone-policing discussed in “Anti-N*gger Machine” suddenly feels like it parallels discussions of whitewashed history textbooks in schools. That song and “911 is a Joke” also manifest the horrifying specter of Black people being victimized by first responders ostensibly called to protect and serve.

The title track and “Pollywanacraka” each address interracial relationships, yet even after 30 more years of their expanding acceptance not only do we still hear “why you wanna date them?” from all corners, but people are as likely to be angered as convinced by evidence and common sense pointing to Africa and the Middle East as the hub of civilization—there’s a clinging to white racial purity and blond Jesus, an actual fear of an actual Black planet. And even as their verses hit tangential topics, other PE songs decried barriers to successful Black entertainers and honest Black messages in media. Although it seems pushed out of the frame by modern streaming media choices, radio’s boycotting of conscious hip-hop was discussed in the buzzing “War at 33⅓,” as swift a rap as Chuck D’s ever committed to tape. Meanwhile, ownership, trustworthiness, and promotion of on-screen storytelling by people of color seems to have inched closer to the demands of “Burn Hollywood Burn.”

The band and its catalog wear warts from these early days, to be sure—Lewis Cole of Rolling Stone suggested that Chuck D and Public Enemy didn’t exist to “promote a perfect political program but to illuminate and reflect raw feelings and experiences.” Still, a clip of Welsing discussing her unfortunate AIDS conspiracy theory introduces the album’s lowest musical point, the skit “Meet the G That Killed Me.” Amid evidence that Chuck has become more tolerant with time, he’s long held that the “G” killing Flavor Flav on tape could refer to many things: guy, girl, gay, gram (of drugs), gangster, germ, government. I’ve always broadly interpreted the “G” as “government,” insofar as I point to the Reagan and Bush 41 administrations’ purposeful institutional ignorance of HIV and the lack of scientifically and socially supportive policy around it. If we wanted a real conspiracy we needed look no further than Washington’s neglect—silence equaled death. And as a modern postscript, those governments who do not learn from epidemiology are clearly doomed to repeat it.

There’s a little more comic relief from Flavor Flav and a few sampledelic interludes from Terminator X and The Bomb Squad, but the second half of the album finds Public Enemy fomenting general revolt throughout. Small wonder, then, that the growls and echoes of “B Side Wins Again” reside here, using the metaphor of the single to describe the battle between the known power (on the A side) and the underdog, the revolutionary, the oppressed. As the Beastie Boys’ “Sure Shot” attempted to make up for past sexism with “Girls,” “Revolutionary Generation” was PE’s mea culpa for 1987’s “Sophisticated Bitch,” its invocations of Mary Mcleod Bethune and Aretha Franklin desperately working to bear Black feminist fruit through today. “Who Stole the Soul?” and “War at 33⅓” each reference the troubling, ongoing dichotomy of America’s construction by Black labor while slave owners received honors like holidays and statues. And of course they close it all out with “Fight the Power,” their joint for Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing that was Chuck D’s tribute to The Isley Brothers’ track of the same name. It returns to the unifying anthemics heard in the front of the album—”Our freedom of speech is freedom of death/We got to fight the powers that be”—with the added bonus of toppling white icons like Elvis (appropriator!) and John Wayne (racist!) before our crash-cut cliffhanger ending.

Chuck D once famously suggested that rap music was TV news for the ears of the Black community, so in 1990 Fear of a Black Planet felt like a lens trained on an unforgiving present. Now, in 2020, Public Enemy feel like they were seers of a separate but equally volatile future, their crystal ball peering at a coming American racial reckoning—a reckoning accelerated by police- and vigilante-engaged violence captured on cellphones and bodycams, envisioned by the Black Lives Matter movement, predated by Rodney King, informed by tragedy in Bensonhurst and Virginia Beach, and ultimately stretching backwards through the civil rights movement, Reconstruction, the Middle Passage. Public Enemy never really registered another album like this, and have barely registered a song like any of these since. Yet Fear of a Black Planet demanded and continues to demand respect for points of view from what Chuck called the “lower level,” whether that be socioeconomic status, the butt end of someone else’s privilege or bias, or the enveloping, liberating throb of bass.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Adam Blyweiss is associate editor of Treble. A graphic designer and design teacher by trade, Adam has written about music since his 1990s college days and been published at MXDWN and e|i magazine. Based in Philadelphia, Adam has also DJ’d for terrestrial and streaming radio from WXPN and WKDU.