Remembering Scott Walker, a visionary architect of the grotesque

There’s an unfinished draft that’s been sitting dormant in Treble’s back end about how Elvis Presley’s stillborn brother, Jesse, inspired two of the weirdest and most chilling songs in rock history: Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds’ “Tupelo” and Scott Walker‘s “Jesse.” It’s a peculiar bit of trivia, perhaps even just an odd coincidence, that has more to do with the creatively twisted depths of two of the most brilliant songwriters of the past 50 years than anything necessarily relevant to what’s going on now. But it’s still a certain obsession of mine—the fact that there’s not one, but two songs about a weirdly sad and creepy bit of pop culture history. Cave’s take is a dark and stormy punk-blues western, a kind of gothic tall tale with a fascination for the grotesque. But Walker took it further—against an ominous riff that sounds like a mangled and ghostly “Jailhouse Rock,” he connected the death of Elvis’ fraternal twin to the September 11 attacks. That’s a unique talent for horror.

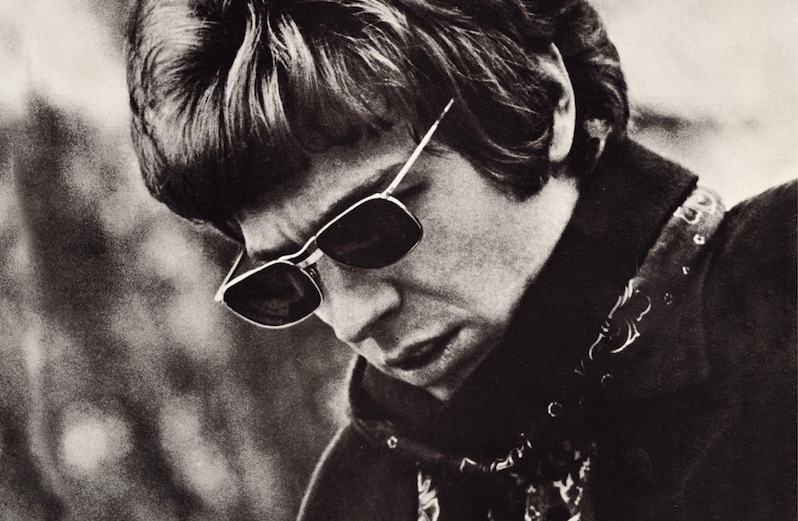

Scott Walker made a career out of defying what was expected of him. After becoming a hitmaker with his group The Walker Brothers—none of whom were related to Walker, who was born Scott Engel—he transitioned into becoming an art-crooner with a fondness for Jacques Brel and increasingly more peculiar compositions, from the darkly grand “Such a Small Love” to the spacier “Plastic Palace People,” which was predictive of his most challenging work several decades later. He then went country for an ill-advised and fairly baffling period, disappeared for the better part of a decade, reformed The Walker Brothers only to release his most terrifying work yet, “The Electrician,” went silent for another seven years, then emerged with the abstract and fascinating Climate of Hunter in 1984, an album that’s loved among those who have heard it, even if that’s ultimately not that many people.

He influenced innumerable musicians, not always in the same way and not always with the same tonal palette. Walker was a difficult artist to get to know or even understand, but he was always fascinating, always challenging. And though he was known for being a recluse, in interviews he had a tendency to come across as charming and funny. In John Doran’s interview with Walker for The Quietus back in 2012, he attempts to describe the images Walker’s music evokes: “you’ve got an entire orchestra full of zombies all murdering each other with their instruments,” he says. as Doran grows increasingly embarrassed by his own description, Walker simply laughs and reciprocates the enthusiasm: “Hey thanks, that’s the next album written!”

Walker was more than a singer, more than a songwriter. He was an architect of ornate darkness, a creator of horrifically compelling narratives. By the time he released 1995’s Tilt in his fifties, he had reached a significant stage of a radical evolution that ultimately found him creating his most radical works late in his career. Tilt’s opening track “Farmer in the City” incorporates elements of poetry written by director Pier Paolo Pasolini in a narrative about his brutal murder, punctuated by an auctioneer’s calls: “Do I hear 21, 21, 21?” He quotes George W. Bush in the menacing “Cossacks Are” from 2006’s The Drift. He imitates Donald Duck during one of the most harrowing moments of that album’s “The Escape,” and punches a large slab of meat as a percussive element in “Clara,” a song about Mussolini and his mistress. Scott Walker didn’t so much sympathize with his subjects or humanize them so much as bring them a kind of tragic intimacy, and he often did so with a wicked sense of humor. At the end of 2012’s “The Day the Conducator Died,” a song about the execution of Romanian dictator Nicolai Ceaușescu on Christmas Day 1989, Walker wraps up the dirge by transitioning into a brief sleigh-bells-and-glockenspiel rendition of “Jingle Bells.” Dark, hilarious, or just wrong? Yes.

Not everybody got Scott Walker’s music, and he didn’t seem all that interested in building bridges to make that easier. When he released 2012’s Bish Bosch, I remember people on social media accusing him of being a troll, which is perhaps a natural response to anyone not used to the kind of torture cycle that Walker built into his strange and unsettling dirges. But that sells his attention to craft and boundless imagination woefully short. He provokes. He subverts and disrupts. But never at the expense of a gripping composition, of which he’s produced dozens and dozens.

I first heard The Drift the year it was released, and I admittedly didn’t understand it. I’m not sure I even really absorbed every sound or idea I was bombarded with, but the experience is hard to forget. I wasn’t sure what this was, just that I knew I needed to return to it, to make sense of it, to feel the hairs on the back of my neck stand up. The experience isn’t one of listening to a rock or pop album, but of being blindly dropped into some kind of surrealist work of horror. Its atmosphere of jarring dissonance and macabre storytelling created a visceral sense of terror, which had an effect that I didn’t quite expect; it made me feel strangely optimistic about the possibilities of what music can do.

Jeff Terich is the founder and editor of Treble. He's been writing about music for 20 years and has been published at American Songwriter, Bandcamp Daily, Reverb, Spin, Stereogum, uDiscoverMusic, VinylMePlease and some others that he's forgetting right now. He's still not tired of it.